One event represented a divided country, resulting in the bloodiest one-day battle ever carried out on American terrain. This Civil War action had favorable consequences for the Union cause based upon a pivotal decision by President Lincoln.

One event represented a divided country, resulting in the bloodiest one-day battle ever carried out on American terrain. This Civil War action had favorable consequences for the Union cause based upon a pivotal decision by President Lincoln.

The other occasion unified a polarized nation for two hours. Conversation and attention focused on a celestial phenomenon. It drew childlike wonder, not wretched political contention.

Last week, my wife and I spent two days in Hagerstown to watch the eclipse on Monday afternoon, April 8, in its totality path. We sat on the lawn of a lovely inn where we spent two nights. The sun-moon dance, spontaneously choreographed, was an

unforgettable spectacle.

Media reports portrayed the eclipse as a unifying event in a country riddled with political division and contention. That is probably correct—though we were not wearing rose-colored glasses.

We will not be around for the next total eclipse in 2045 in the United States.

Equipped with special glasses sold by the global Amazon empire, as well as my iPhone 13 and its camera, I proceeded to watch the darkening of the sun by the passing moon. At the end of an hour, the sun, as viewed by my aging eyes, looked like a single quotation mark. The moon’s passage was undeniable.

Left hanging by my focus on the eclipse, readers may wonder about my lede paragraph. Civil War devotees know fully well about the Battle of Antietam, known to Confederate soldiers as the Battle of Sharpsburg. It was the bloodiest one-day battle in the Civil War.

It also precipitated Lincoln’s release of the Emancipation Proclamation. This document decreed that all enslaved people in the Confederacy were free.

Thus, it crystallized the military mission. It enabled enslaved people to join the Union’s fight against the rebellious southern states. It discouraged Britain and France from supporting the secessionist states.

On September 17, 1862, roughly 23,000 U.S. Army and Confederate soldiers were killed, wounded or missing at Antietam. General Robert E. Lee’s forces withdrew.

Fought on lovely, rolling farm fields outside Hagerstown in Washington County, the Battle of Antietam was a dark and dreadful confrontation. It symbolized the lack of political sunshine between the northern and southern parts of our country.

War was an unfortunate solution to longstanding enmity between the industrial north and agricultural south. Civility was eclipsed by immovable perspectives on slavery.

Our morning visit to the Antietam battle site was a sobering experience. It shadowed my impression of the astronomical phenomenon later in the day. Our world, now and past, always offers contradictory experiences and viewpoints.

To fully appreciate and record the eclipse, I shot numerous pictures of the eclipse with my dependable but limited IPhone. My photography was analogous to whistling in the wind. My output included wonderful (maybe not) shots of the sun and clouds.

Any movement of the moon was sorely lacking in my picture-talking. My effort was ridiculous but necessary to satisfy my restless soul.

When the moon did cover the sun, the effect in Hagerstown was comparable to a sudden burst of cloudiness. In Buffalo, NY, darkness did materialize, so I was told.

A celestial happening and human destruction are distinctly different but connected by a sense of wonder.

Devoid of any human control, an eclipse captures our fascination, as do stars like Mars and Jupiter. The unknown pierces our indifference to all but our nourishment by the sun and our addiction to moonlight.

A battlefield, however sedate and peaceful as a relic of the past, summons our wonder about the terror of war. Why are wars so tied to the human condition? Why must we fight and kill? Do the results justify the inevitable death, maiming, and psychological damage?

It is rather late in this essay to raise these long-debated and troubling questions. I have no answers. I simply wonder.

As I do about a sky inhabited by stars—and man’s continued quest for scientific knowledge about the “way beyond”— I bemoan our human appetite for war.

Columnist Howard Freedlander retired in 2011 as Deputy State Treasurer of the State of Maryland. Previously, he was the executive officer of the Maryland National Guard. He also served as community editor for Chesapeake Publishing, lastly at the Queen Anne’s Record-Observer. After 44 years in Easton, Howard and his wife, Liz, moved in November 2020 to Annapolis, where they live with Toby, a King Charles Cavalier Spaniel who has no regal bearing, just a mellow, enticing disposition.

Maybe it’s due to the fragility of our aging infrastructure made apparent by the tragic demise of the Francis Scott Key Bridge, or maybe it’s just some misplaced molecule wandering through my brain that is reminding me to learn more about the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but whatever the reason, I’ve woken the last few mornings thinking about the Colossus of Rhodes. Which, of course, leads me to consider Salvador Dali’s surreal depiction of that ancient monument, which in turn, steers me in the direction of Emma Lazarus’ poem, “The New Colossus,” which, as we all know, is inscribed upon the Statue of Liberty… I’m sorry; I didn’t mean to burden you with the strange meanderings of my own ancient grey matter. Welcome to my world.

Maybe it’s due to the fragility of our aging infrastructure made apparent by the tragic demise of the Francis Scott Key Bridge, or maybe it’s just some misplaced molecule wandering through my brain that is reminding me to learn more about the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but whatever the reason, I’ve woken the last few mornings thinking about the Colossus of Rhodes. Which, of course, leads me to consider Salvador Dali’s surreal depiction of that ancient monument, which in turn, steers me in the direction of Emma Lazarus’ poem, “The New Colossus,” which, as we all know, is inscribed upon the Statue of Liberty… I’m sorry; I didn’t mean to burden you with the strange meanderings of my own ancient grey matter. Welcome to my world.

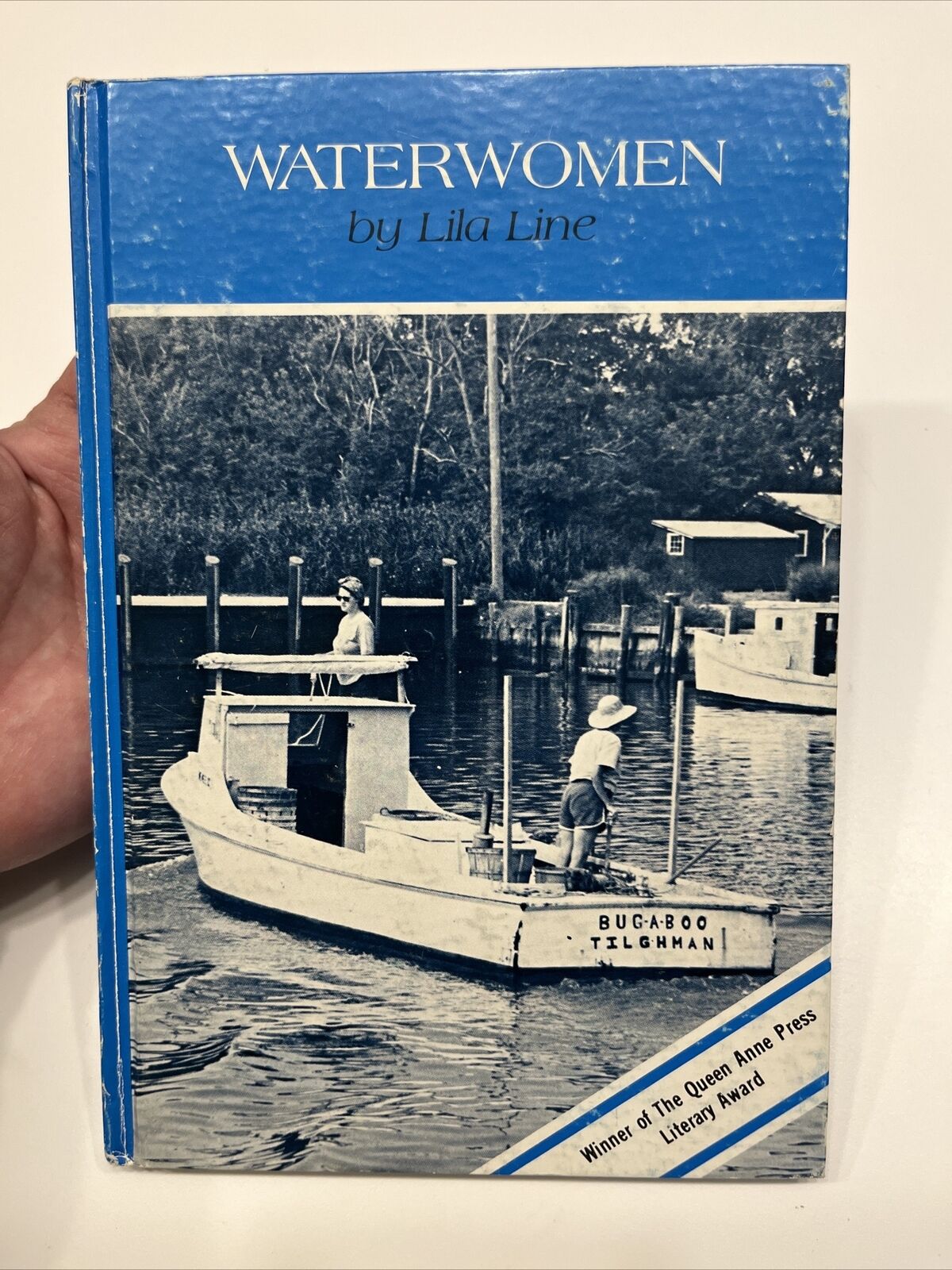

She won the Queen Anne Literary Press Award for her 1982 book

She won the Queen Anne Literary Press Award for her 1982 book

So there I was, Honorary Vice President of the Four Monkeys Babysitting Club for the next three days. And on Herself’s birthday weekend, to boot. How did this happen? I guess I owe you an explanation…

So there I was, Honorary Vice President of the Four Monkeys Babysitting Club for the next three days. And on Herself’s birthday weekend, to boot. How did this happen? I guess I owe you an explanation…