“Hi, this is Lila’s machine…”

Whenever I called my friend Lila Line, that’s what I heard and I loved to hear it. From 1972 to 1998, writer/photographer Lila Line lived in this area and graced our presence with wit, empathy, and charm. I was lucky to have met her. And like all circuitous meetings, the reason we met was based on the sorrow we both had in our lives.

Lila Line

I don’t remember the precise moment we met, but I know how we met. It was the summer of 1988 at the Adult Children of Alcoholics meetings held in Easton. My late uncle thought it would be great for the both of us to attend the meetings together.

This was the era when Al-Alon wasn’t enough, and adults used these classes to exorcise their old ghosts.

At the very beginning, I found Lila very interesting. She was about 5’4, with gray hair cut in a bob, tanned skin, a prominent nose, and a very kind face, especially her eyes. For some reason her speaking voice reminded me of Barbra Streisand at times with its sweet, girlish, East-Coast lilt and charm. It was at once high yet deep. When Lila spoke, in joy or seriousness, you listened — very intently.

The meetings were filled with upper-middle-class people, so I wasn’t going to see anyone I knew there. My uncle could talk the paint off the walls so he was right at home. For better or worse, my uncle didn’t like to tell the same story twice, so he left the meetings, and I stayed.

Oddly enough, I don’t remember Lila in the meetings themselves. The time was often taken by flashier speakers with their lines at times rehearsed and filled with cinematic gestures. In fact an infamous artist who left a trail of tears on both the Eastern and Western Shore was at the meetings acting like he was auditioning for Ryan’s Hope.

Regardless of the theater, Lila and I found one another quickly and hit it off immediately. It turned out she lived not more than a mile away from me in Royal Oak.

I was interested in writing and little did I know I’d have someone so close by with such an enviable career and an interesting life. And what a life it was…

Lila Levinson Line was born in Brooklyn in 1924. Lila was a well-to-do yet down-to-earth housewife with three sons when she decided to go for her dream of being a writer at 36 years old. This wasn’t always done as Lila recounted in a 1982 article from The Star Democrat.

“….I realized I was bored with television, and I needed something stimulating. I decided to go to college at the University of Maryland after my third child was born.” Lila continued…

“I knew I loved to write. There was something sitting there that needed to come out.”

That’s the way a lot of writers feel and the life that Lila personified. After all, she started writing at 14, wrote a novel during that time, and she also wrote poetry and short stories.

Lila was an editor at the Naval Ship and Development Center. If anyone’s ever read their work, it’s difficult to decipher, and no doubt Lila makes it easier to grasp. Lila took years of writing classes at the University of Maryland and Montgomery College.

After living in Washington, DC, Lila became a freelance writer at almost 50 and started to teach at Chesapeake College.

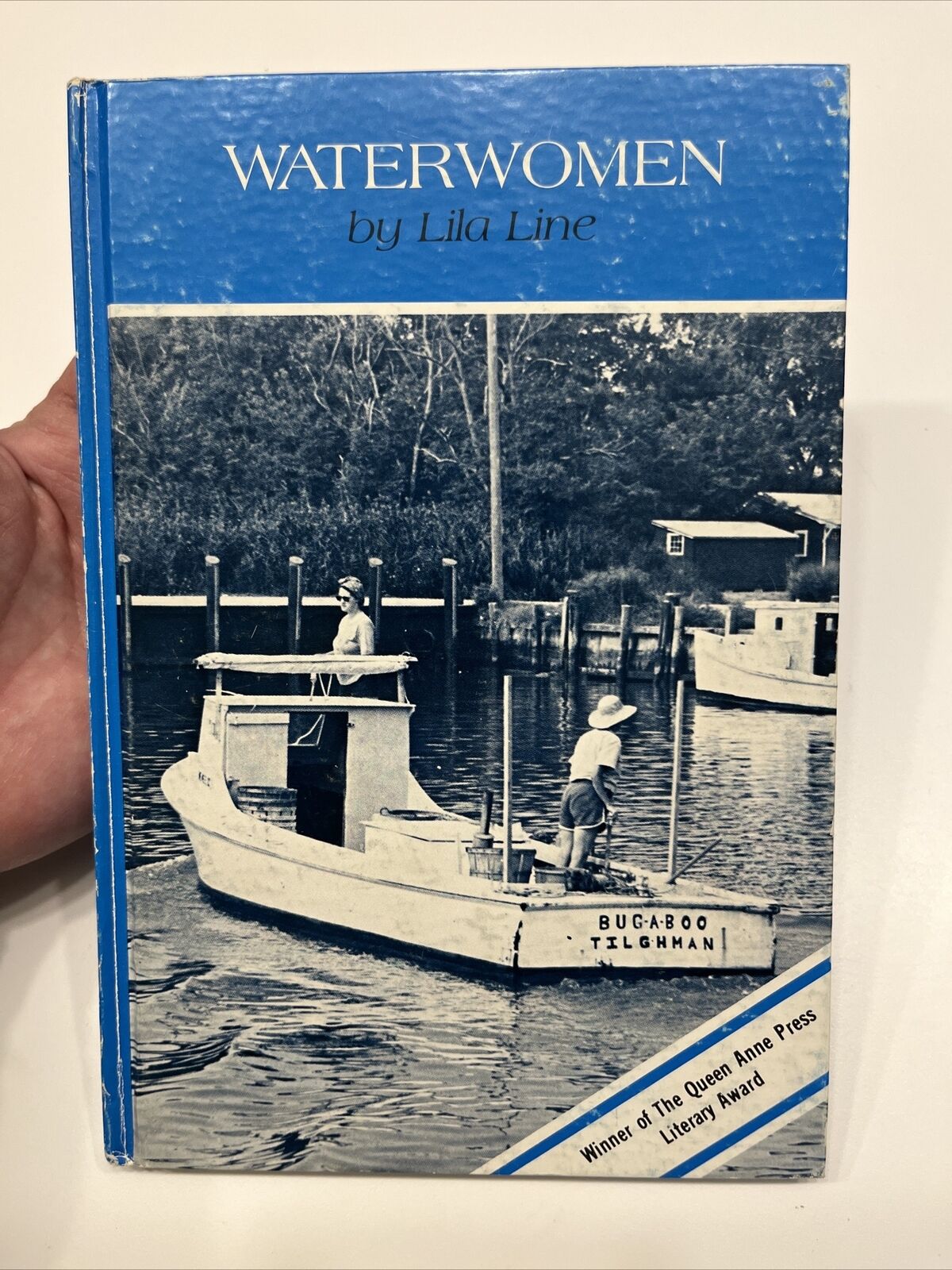

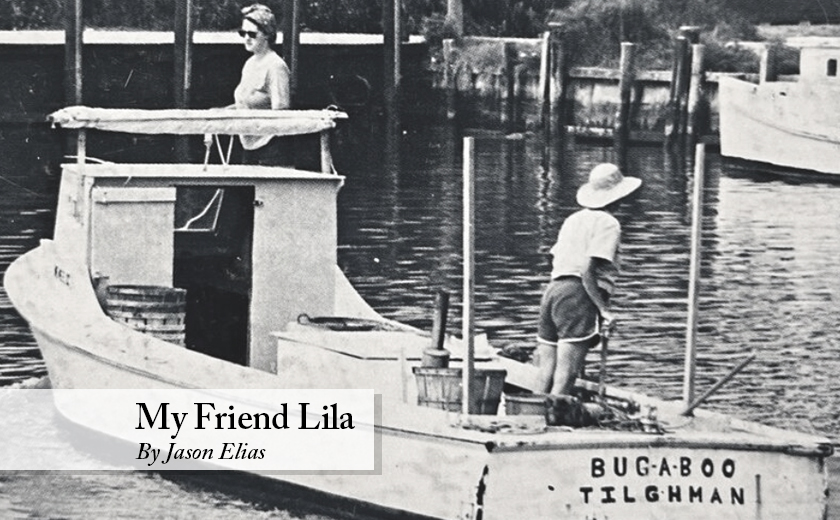

She won the Queen Anne Literary Press Award for her 1982 book Waterwomen in which she wrote and did photography. The prestigious award was under the aegis of Arthur Houghton. This book, in particular, got Lila write-ups in The Washington Post and The Baltimore Sun.

She won the Queen Anne Literary Press Award for her 1982 book Waterwomen in which she wrote and did photography. The prestigious award was under the aegis of Arthur Houghton. This book, in particular, got Lila write-ups in The Washington Post and The Baltimore Sun.

During the time we met, Lila had released her next book, Granddaddy Builds A Bugeye. Lila was working on books, teaching and I was handwriting the world’s worst poetry in Mead notebooks and later hunting and pecking on my typewriter.

After a while I let Lila see my work. She liked it. What I loved about Lila is that she told the truth, she went through my poems with a red marker, putting lines through extra words and commenting on lines she particularly liked. I still have few of the poems she worked on with me, her notes were as good as a byline.

In a way, Lila gave me an upfront view of what a writer was, and I liked it. It was fortuitous that I met Lila when I did. The area didn’t have a lot of opportunities for people who wanted to write and sometimes wanted to read.

The 80’s were often rough to navigate in the area. In comparison the 70’s were halcyon days. As I stumbled into young adulthood the area often wasn’t as kind as it could have been, I was followed in stores from broken down junk shops to JCPenney. Meeting Lila was a lifeline, respite and just a breath of fresh air in an often stagnant community.

Immediately Lila and our friendship was “different.” I never called her “Ms. Line” the or any variations thereof. We never talked about race, she never mentioned it and neither did I.

Since Royal Oak is a small town, especially so in those days, I got to see Lila in her element on an often daily basis, driving to and fro. She had a brown Honda Accord with a bike rack, I’d always be happy to see it on the road. She would also ride her bicycle on the roads.

Our lives seemed to intersect in more than a few instances. To add to the list of similarities, we both were in psychotherapy and we both needed it. For about two minutes, we even shared the same psychotherapist; she didn’t like him, and I saw him for years.

What I got from Lila even early on was a sense of the truth and a kindness. I invited her to my house and I remember how kind she looked and how she acted with my mother.

Although I didn’t quite grasp it then, it was really special to have someone of Lila’s stature to look at my work, tell the truth about it and most importantly not be cruel about my nascent dream. I remember Lila was giving me instructions on how to submit to magazines and papers, she told me to send the work and include a “SASE.” I didn’t know what a “SASE” was until she told me it was a self-addressed stamp envelope.

At the same time I had interactions with writers that weren’t so charmed. My psychotherapist whose cousin was a well-known poet looked at my words and wasn’t pleasant at all. Another poet whose book I carried around with me like a diary visited the Talbot County Free Library, I don’t remember a single word he said but I remember the indifference in his eyes when I asked a question. In comparison Lila was gentle with me.

In all the years we knew one another, there was never one cross word. She always took time even though her schedule was always full.

Lila took extended vacations to see fellow people from her religion, the Quaker faith. She attended the Third Haven Meeting House in Easton. It wasn’t uncommon to see her car there. The religion and the meeting place provided sustenance.

Talbot County’s bucolic scenery also provided calm. Lila described how she felt in the aforementioned 1982 Star Democrat article that featured her…

“ Nobody told me about Easton and Oxford and Tilghman Island. I fell in love with all of it.” Lila continued…

“My sister hated it down here. She told me not to come down. I had to see what I would hate.”

There wasn’t much to hate in Talbot County. Although she was a habitue of New York and later Washington DC, she truly took to life on the Eastern Shore. Unlike some of the transplants, she didn’t lose her identity and with her keen writer’s eye she knew what made the area work and what was its backbone, the water, the water men and water women who became the subjects of her books and stories.

Lila made a home on the Eastern Shore, in Royal Oak. Her water view cottage was called, “A Place For Lila” and she told that the home was finally a place, for her.

After knowing Lila a few years, I truly grew comfortable with her. I felt very comfortable in her home. To me, it was the archetypal writers home, a bit lived-in with family photos, lots of paper, a typewriter nearby and clips not far from view.

Lila supposedly retired from teaching in 1992, but her teaching continued, and she often advertised in The Star Democrat, offering writing lessons for crafting biographies and later autobiographies. She still taught classes for Chesapeake College and Washington College Academy of Life Long Learning.

Any fans of the late 80’s and 90’s Star Democrat and or fans of Lila Line remember her appearances in the Letters To The Editor section. Lila’s comments were often terse, humorous and correct. She offered a lot of passion in her words whether it was supporting a local teacher friend who was dismissed or lamenting at how friend and renowned poet Gilbert Byron was treated in this area.

As the proverb goes, it takes a village, and it took a village to get me from point A to point B. A close group of people, including my mother, Dr. Robert Lea, and family and friends, kept me afloat through debilitating illness, false starts, and depression. In fact when I was having trouble living in the same household as my grandfather, Lila offered me a place to stay. I had to decline like her house was a sanctuary. In the best of times, mine was too.

Lila’s steady hand guided me as I stopped writing poetry and began writing other things like album reviews. In short, it didn’t matter what I did, she loved to see me active. In fact one time she said that when she was driving past my house at night she’s look to my window to see if the light was on to see if I was listening into music or writing. That was one of the sweetest things anyone has said to me.

By this point, it had been about ten years since we first met. We had a nice shorthand with our conversations. She gave me dating tips and told me nothing was wrong with me, except for the way I walked. A lot of times when I’m walking, I’ll think Lila and try not to walk like a duck.

After publishing a good amount of articles, I finally went to one of Lila’s classes. For some reason, I wasn’t all that into it. She knew it and looked at me with a bit of exasperation, but we couldn’t hide the fact that we were glad to see one another. Of all of the teachers I’ve had, I loved to see Lila in his element. All of the shyness she had disappeared as her voice became more firm and her countenance more imposing. I can still see her hovering over her students and answering questions, it’s one of the best times I’ve ever had.

Lila continued to stay busy and wrote an article about The Fields family for the Star Democrat. It followed the leads of Waterwomen by giving the subject integrity and put a face on one of Bellevue’s most known and loved families. Lila featured the family patriarch and gave a face and presence to people whose virtues had often go unsung.

By the late 90’s Lila started to have an acrimonious relationship with the person who owned her house as the rent started skyrocketing. She talked about it a few times and before I knew she was planning to move to Chestertown. Oddly enough, it was a place where I had family. I never saw them and it’s a place that was longer than a bike ride away.

To be honest, I was a bit resentful that she was leaving, although I understood. She visited me in my yard where I used to play records at an ear-splitting volume, we talked a while and said so long. She knew I loved records, so she gave me a copy of Barbra Streisand’s A Happening At Central Park that she found while she was packing her things.

Her energy and charm loomed large. The area wasn’t ever quite the same without seeing her wave from her car or telling me stories about what she saw on her bike rides. The scenery became less eventful and the language tin-eared.

Not surprisingly, Lila took to her new environment very quickly and continued writing, teaching and advising. Lila later wrote an article for the Three Haven Newsletter called “Quakers Are Friends” it was about where she’d been and her recent travels.

“One of the functions I attended in Chestertown, which I will long remember and value, was a memorial service for 12-year-old Lucy the Goose, where the Mayor of Chestertown delivered a heart-rendering sermon in honor of Lucy she delivered beside a bridge laden with dozens of visitors, a service I shall never forget.”

That was Lila’s gift, making a reader hang on every word. As a good friend, I was happy that she did get some comfort in her new environment. To be honest, I wasn’t overcome with joy about her new life and digs. I was jealous and missed my friend. I never let on though, I sent her clips from articles and reviews I did and she always reminded encouraging.

We had exchanged letters and I always kept them and I called her on one Sunday when I was hardly working at the Chesapeake Center. It was great to hear her voice again. Out of all things she said, I was struck when she said I sounded mature. It was something I had been putting off for years, to hear it from Lila was great. I wasn’t writing poetry or much of anything, but I was existing which is something she helped me with.

Lila was always in my thoughts, I had talked about her to a friend and for longer than I care to admit, I put off searching for her online. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s because of the fact that I hadn’t heard from her in so long and I didn’t want to see bad news. I decided to look her up and saw her obituary. I wasn’t surprised. It was like I already knew. I didn’t take her death well then and I don’t now. It still breaks my heart that someone with such wonder, distinct energy and life is no longer here. But then again, maybe she is.

Writers like actors and such seem to have an immortality. Within the click of a channel or visiting a website, the artist’s work is alive. That kind of omnipresence and longevity is what a lot of writers strive for.

Lila’s work still is being referenced in present day articles, YouTube videos and on display at the Maritime Museum. Lila’s life still impacts the ones who knew her, the students she touched and the friends she made. When I talked with a friend, local and renown writer Helen Chappell she said simply,

“Lila was totally original, there never was and never will be another one like her.”

To know Lila was to love her and I was lucky to meet someone so caring to me and so unique to this world.

Jason Elias is a music journalist and a pop culture historian.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.