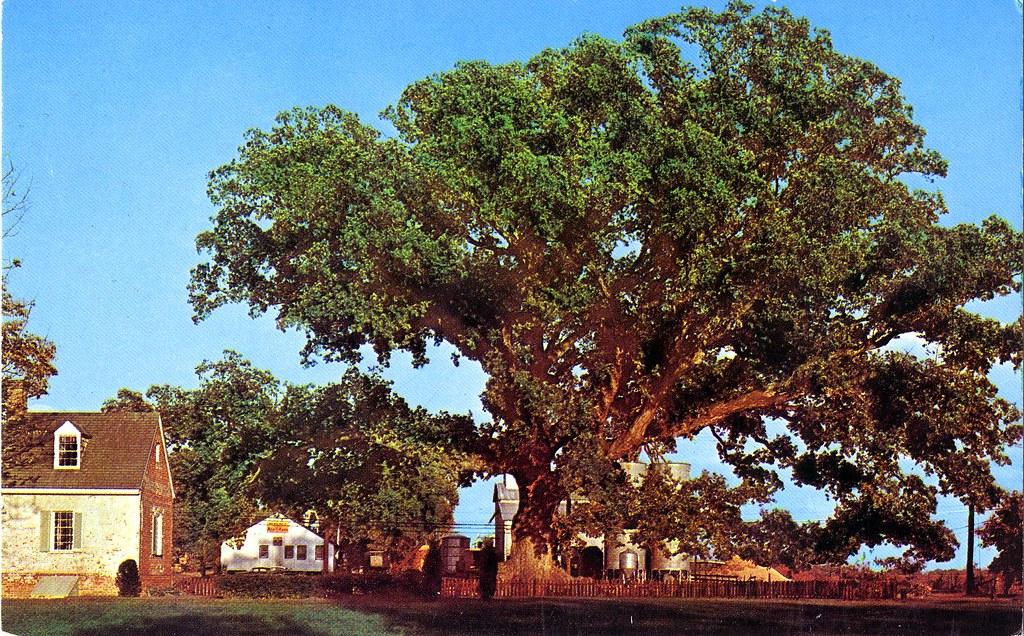

Author’s Note: “Elm Trees” started as my memory of watching the daily removal of the last trees destroyed by Dutch Elm Disease. Period photos of Clinton County, New York show the damage to the landscape caused by the disease. Soon even long-time residents would have only a vague memory of elms. As I wrote each draft during the height of the pandemic, the trees took on a haunting sense of fear and helplessness.

Elm Trees

One September I lingered in a town

with no intention

to stay. Twilight clung

to any warm breeze. On narrow streets

there were regal old houses in need of repair.

Elm trees lined the narrow

sidewalks, their heavy limbs bare,

each trunk’s decaying girth

marked with a slash of white paint, one

crooked, careless X

warning of Dutch elm disease.

I waited for a job; the elms

waited for nothing

but to be cut down. Every day

there was a shrill of chain saws.

At times that shrill

must have been no more

than a faint unease, a faint

whisper of failure, of falling, of absence.

⧫

Michael Carrino is a retired lecturer in the English department at SUNY (State University of New York), Plattsburgh. He was co-founder and poetry editor of the Saranac Review, and he has had seven books of poetry published, most recently “Until I’ve Forgotten” and “Until I’m Stunned,” as well as individual poems in literary journals. He holds an MFA in Writing from Vermont College.

Delmarva Review publishes compelling new poetry, fiction, and nonfiction selected from thousands of submissions annually. Designed to encourage outstanding new writing, the literary journal is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, now in its 15th year. Financial support comes from tax-deductible contributions and a grant from the Talbot Arts Council with funds from the Maryland State Arts Council. Website: www.DelmarvaReview.org.