Ariana Sutton-Grier is a distinguished scientist with expertise in coastal ecosystems. In particular her research has focused on the role these ecosystems—both the coasts and associated wetlands—play as living infrastructure that improves climate resilience by helping protect against storm surges and rising sea-levels. These coastal ecosystems also turn out to be important in storing large amounts of carbon that would otherwise escape to the atmosphere as greenhouse gases, accelerating climate change. In the Chesapeake Bay, they are also important for maintaining fisheries and as recreational assets. Dr. Sutton-Grier is a visiting professor at the University of Maryland and recently gave an invited lecture at that university’s Horn Point Laboratory, excerpted here by permission.

In a follow-up interview, Dr. Sutton-Grier made clear the importance of living or green infrastructure on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay and preservation or restoration of wetlands. Not only do salt marshes and sea grasses and oyster beds help reduce wave energy and inland flooding, they survive extreme storm events like hurricanes better than bulkheads and stone riprap. Healthy coastal ecosystems also adjust better to rising sea levels by being able to grow and keep pace with rising waters. Moreover, these coastal ecosystems help slow climate change by capturing and storing large amounts of carbon for long periods of time. On a per acre basis, in fact, coastal ecosystems often store more carbon than the world’s tropical forests.

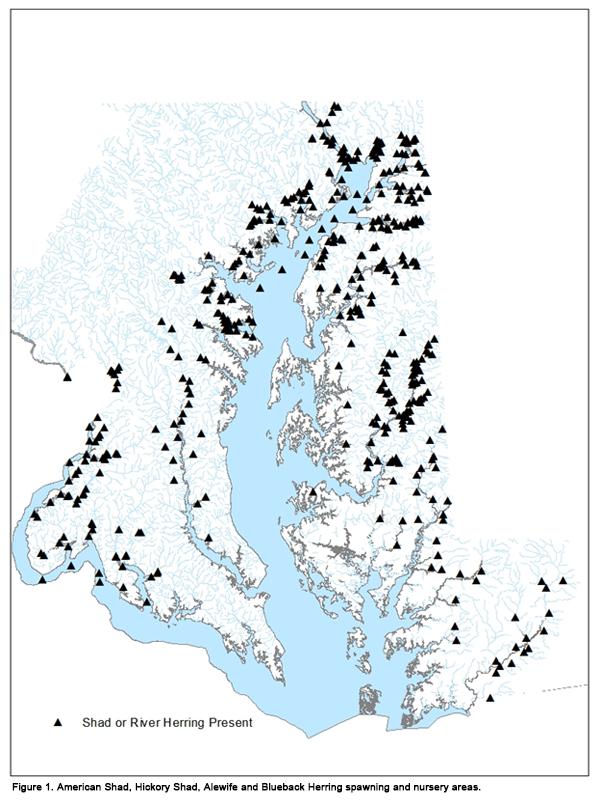

Restoring and protecting coastal wetlands—and potentially even creating new wetlands—could enhance carbon capture and storage, and might be able to be partially funded by carbon capture credits. Maryland has some 3100 miles of tidal shoreline around the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries and along the Atlantic coast—a remarkable resource. Moreover, Sutton-Grier points out, the region around the Bay is mostly flat, meaning that as sea levels inevitably rise, coastal wetlands can potentially migrate inland, preserving both fisheries and recreational opportunities, and their unique carbon storage capabilities, for the long term.

Maryland Secretary of the Environment Ben Grumbles recently underscored the importance of green infrastructure on the Eastern Shore. In response to a question from the Spy, he identified the need for more such efforts as perhaps the most important step that Maryland could take in improving the resilience of the Chesapeake Bay and its surroundings to rising sea levels, storm flooding, and other impact of climate change.

Preserving and perhaps expanding coastal wetlands around the Bay might be the most significant green infrastructure opportunity. It would involve significant societal tradeoffs, but could provide a way to offset rising sea levels and storm surge flooding. Indeed, sea level rise is already causing salt water intrusion and frequent flooding in low-lying areas such as much of Dorchester and in other parts of the Eastern Shore, making farming difficult and threatening some residential and commercial areas. If such activities were equitably re-located, and replaced by tidal marshes and other wetlands, the entire Bay region would be better protected against rising waters, while enhancing fisheries and recreational opportunities and also helping to slow climate change.

Al Hammond was trained as a scientist (Stanford, Harvard) but became a distinguished science journalist, reporting for Science (a leading scientific journal) and many other technical and popular magazines and on a daily radio program for CBS. He subsequently founded and served as editor-in-chief for 4 national science-related publications as well as editor-in-chief for the United Nation’s bi-annual environmental report. More recently, he has written, edited, or contributed to many national assessments of scientific research for federal science agencies. Dr. Hammond makes his home in Chestertown on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.