All Saints’ Day on November 1, honoring Christian saints and martyrs, was celebrated in the Eastern Church as early as the 4th Century. All Souls’ Day on November 2 was instituted in the 10th Century by St. Odilo of Cluny. It was a day of prayer for deceased family members in Purgatory awaiting entrance to heaven. These two days are celebrated in the Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran churches.

William Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905), a leading French Academy painter during the reign of Napoleon III (1848-1870), painted “All Souls’ Day (Day of the Dead)” (1859) (58’’x41’’). The work was popular, and Bouguereau was commissioned to paint several versions of the subject. Two women dressed in the black of mourning have come to the cemetery to lay wreaths at the grave of their deceased relative. Bouguereau painted in the Neo-Classical style, considered to be the revival of Italian Renaissance art. The women are posed in the traditional triangular composition. Circular and half-circular shapes are repeated throughout the work: the women’s heads, the hair braid, the curved positions of their hands, the memorial wreaths, the design of the cross, and the curved outlines of their bodies. Viewers’ responses to Bouguereau’s depiction of realistic detail and communication of profound emotion increased his popularity in France.

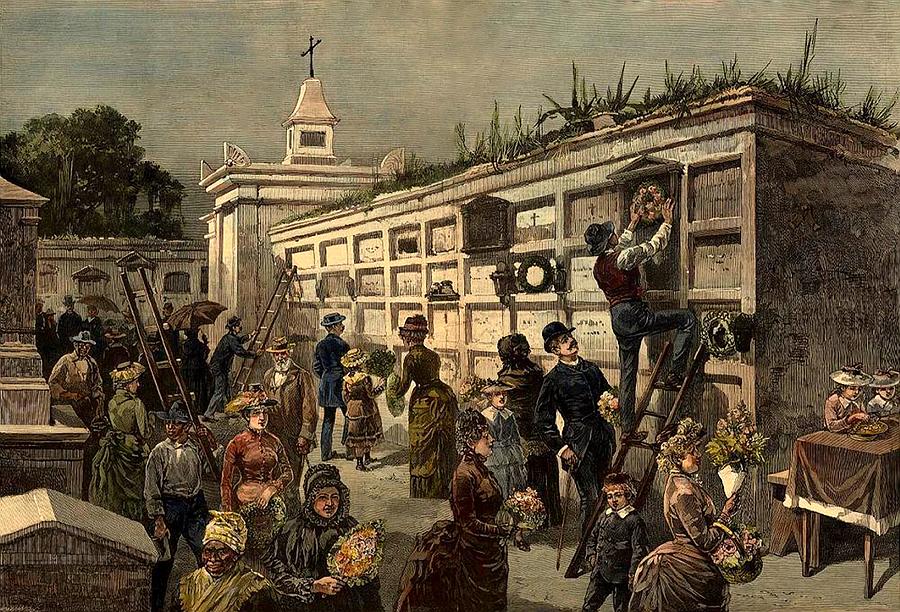

“All Saints’ Day in New Orleans, Decorating the Tombs in One of the City Cemeteries” (1885) was drawn by American sketch artist and illustrator John Durkin (1868-1903). Durkin’s work appeared often in Harper’s Weekly during the 1880’s. He attended the 1885 New Orleans World Fair and illustrated several scenes. By the 19th Century, All Saints’ Day had become an enormous community celebration. Durkin depicts citizens of all classes and races coming to the cemetery, many to honor the dead, but others to enjoy the festivities. Families whitewashed the tombs and decorated them with wreaths, flowers, beads, prayer cards, and other mementos. They brought large picnics. Music, dancing, drinking, and sharing stories of loved ones were a part of the festivities. At the far right of the scene, two females are enjoying their holiday picnic. Durkin’s print omits one additional element: the thousands of lit candles placed around the tombs in the cemetery, even in daytime.

An 1843 article in the Times-Picayune described the event: “Repairing at rather a late hour to the Catholic Cemetery, we found a dense throng of people entering it, for which the gateway seemed vastly too confined, such were the numbers pressing in. Nor was there any distinction of colors, class, or nation. People of all hues and derivation, and of both sexes, were crowding for admittance; some to honor the departed, others to witness the singular observances.”

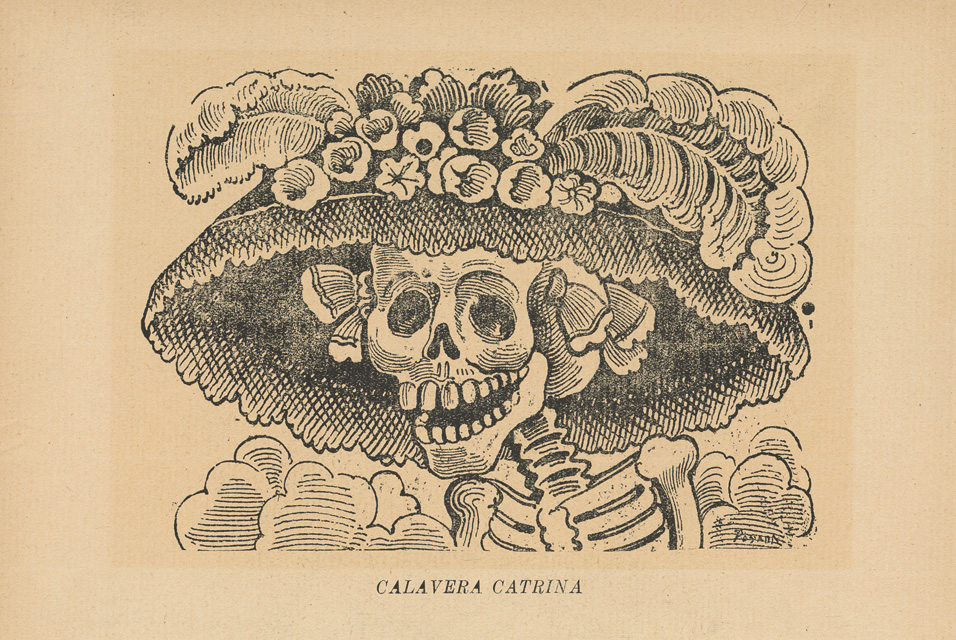

In Mexico, All Souls’ Day (Dia de Los Muertos) is celebrated on November 1 and 2. The gates of heaven open at midnight on October 31, and families go to cemeteries to be with the spirits of their loved ones. The Day of the Dead is a combination of the ancient Aztec goddess Mictecacíhuatl (Lady of the Dead), who guards the bones of the dead, and All Souls’ Day, brought to Mexico in the 1500’s by the Spanish conquerors. “Calavera de la Catrina” (1910) (13.5’’x9’’) (zinc etching) is Mictecacíhuatl (renamed Catrina) by Mexican artist Jose Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913). Calavera (skeleton) of Catrina wears a large hat decorated with flowers and feathers. It has become an iconic image for the Day of the Dead.

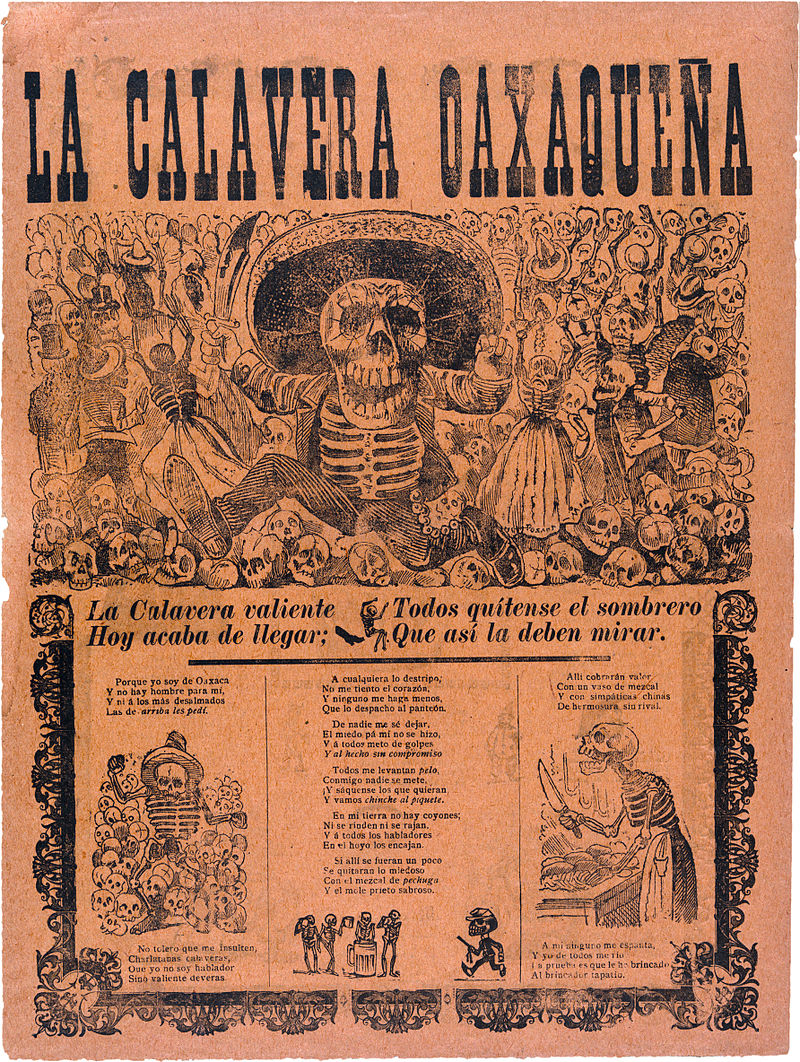

Posada’s depiction of the male skeleton became synonymous with The Day of the Dead. The male skeleton is depicted with skull and rib cage. It is dressed in the style of the 17th Century Mexican Charro. The Mexicans were first enslaved by the Spanish colonists, but later employed as cowboys to work on the haciendas. The Spaniards brought horses to Mexico, but only those natives who were employed were allowed to ride horses. The Charro outfit was developed because it was forbidden to dress like a Spaniard and perhaps to be mistaken as a member of the Spanish upper class. Charro was a derogatory term meaning crude, unsophisticated, and crass. In response, the riders developed a stylish black outfit decorated with white embroidery that included pants, jacket, vest, shirt, bow tie, belt, and a wide-brimmed Charro hat. These seven items were always included in a Charro outfit. For the Charro, the best horsemen in Mexico, the outfit became a symbol of chivalry, braveness, and pride.

“An Altar in Their Memory” (2019) (7,000 square-feet) was constructed by internationally known Mexican artist Betsabee Romero (b. 1963). The work was commissioned by the Latino Arts Project for the Design District center in Dallas, Texas. It was the second exhibition of the Latino Arts Project. Romero’s art uses traditional Mexican elements and reinterprets them for the present day. Romero stated: “Day of the Dead is a celebration that has become very global, but with death, you are working with a concept that is very terrifying. The altar becomes an experience. It’s something that you can walk inside and participate with…An altar is done as an offering. In this case, this installation is dedicated to all people who have passed away due to gun violence and to migrants who have passed because they were trying to get a better life crossing the border.”

The traditional elements for the Day of the Dead altar are included. Romero provides a large gate lined with marigolds, the flower of dead, providing a path for the spirits to approach the altar. Yellow skulls decorated with flower designs, with holes where the pistil would be, line the rear of the gate.

Traditional punched tissue paper (papel picado) hangings with black human targets at their centers are placed at the right and left sides of the gate. The punched holes represent bullet holes. The yellow paper cuttings surrounding the figures are skulls. The borders are colorful punched paper flowers. Lining the walls are strips composed of images from the Aztec Codex Borgia, the 16th Century manuscript depicting the calendar, gods and goddess, and rituals.

The installation “Ofrenda” (offering) is set up in another room of the exhibition. The four elements earth, wind, water, and fire are represented. The candles at the top of the altar represent fire. Wind is represented by the papel picado that blow in the wind.

Earth is represented by loaves of bread (pan de muerto), the aroma feeding the souls of the dead. Containers of water satisfy their thirst after the long journey. A container of salt is present for purification. The aroma of incense guides the souls. Sugar skulls form the pistils in the cut paper flowers. Skulls painted with fruit and flowers, paper marigolds, and papel picado skulls add to the colorful altar.

In 2022, Romero created a Day of the Dead altar at the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, London. Day of the Dead is celebrated with altars, parades, and cultural events in Los Angeles, New York, Spain, and elsewhere.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.