Teresita Fernandez was born in Miami in 1968. Her Cuban parents and relatives came to American in 1959 after the Castro takeover. Fernandez spent much of her childhood learning from her aunts and grandmother, who had been highly skilled couture seamstresses in Havana. She received a BFA from Florida International University in 1990 and an MFA from Virginia Commonwealth University in 1992. Her art is inspired by the geological structure of the landscape, the natural phenomena of storms, fires, and hurricanes, as well as history and culture.

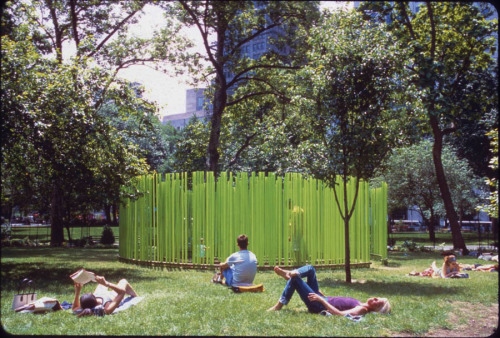

“Bamboo Cinema” (2001) was commissioned during the second year of the project to revitalize Madison Square Park in New York City. The work consisted of plexiglass tubes of different diameters and heights up to 8 feet that were silk-screened in bright colors of greens and yellows. The tubes were embedded in concrete in concentric circles. As visitors walked through the circles, their experience constantly changed. The bamboo-like poles acted as a shutter in an early movie camera, giving the appearance of flickering, thus the title of the work. The installation used both the landscape and the experience of watching early films.

The Madison Square Park revitalization project has continued since 2000, and it has included such artists as Maya Lin, Alison Saar, and in 2023 Shahzia Sikander. Fernandez returned to Madison Square Park in 2016 with “Fata Morgana,” a 500-foot-long sculpture consisting of six sections. Hundreds of mirror-polished metal discs with perforated patterns suggesting foliage were suspended like a canopy over the park pathways. Fernandez’s title came from the Latin phrase meaning mirage, and it referenced Morgan le Fay, King Arthur’s half-sister who possessed magical powers.

Fernandez said, “I see the park as a system of arteries reflecting and distorting urban life. It [“Fata Morgana”] will reflect the landscape on a grand scale, as your own reflections are seen from above and are shaped by other people and by the environment. It takes the whole park and unifies it. Like a horizontal band, it becomes a ghostlike installation that both alters the landscape and radiates golden light. It also will be a visual barometer of what changes around it during different seasons and times of day.” Over 10 million people have walked under its canopy.

“Fata Morgana” was the largest public art project placed in Madison Square Park. Fernandez’s piece inspired the Madison Square Park Conservancy to create a partnership with the Ford Foundation to organize the U.S. Latinx Arts Futures Symposium. Latinx artists, museum directors, curators, educators, and others gathered to discuss the omission of Latin artists from art institutions. The Whitney Museum of American Art hired the first curator for Latinx art as a result of the Symposium.

Fernandez’s works present her visualization of the elements of nature. She explored the image of water in a 2009 commission titled “Stacked Water” that covered 3,100 square feet of wall with blue cast aluminum strips. “Drawn Water” (2009) (121”x43”x86”) consists of a steel armature made to flow downward like a waterfall. Machined graphite rocks provide an image of the water flowing into a river. On a long wall behind “Drawn Water,” “Epic I” (2009) (131.5”x 394”x1”) consisted of 27,000 small pieces of raw mined graphite attached to the wall with magnets.

“Epic I” was inspired by another natural phenomena observed by Fernandez: “It was inspired by a meteor shower. Oftentimes, I use materials that are mined to refer to cosmic references. Graphite is mined, and it is a very lustrous material. It catches the light in a certain way.”

From 2009 until 2017, during the Obama presidency, Fernandez served as the first Latina member of the United States Commission of Fine Arts. Fernandez stated, “I am quietly aware of how my personal history is everywhere in the work. But this manifests itself, like every other reference, very subtly and solemnly, and always unannounced, without being reduced to oversimplified labels or explanatory narratives. That sense of intimacy and subtlety in the work is key for me.”

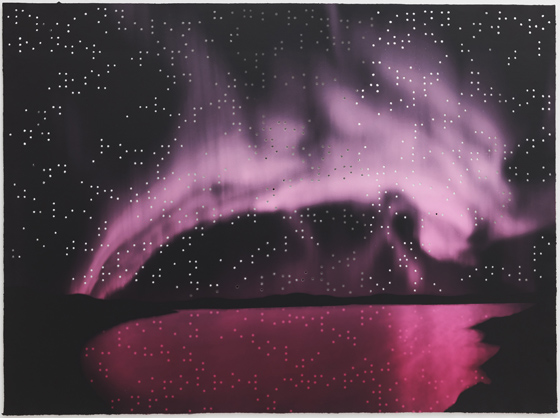

“Hero and Leander” (2011) (49”x21”x66”) is created from handmade colored paper pulp to represent the effect of the Northern Lights. Punched holes are the glittering stars in the night sky. The title was inspired by the Greek myth and the poem by Chrisopher Marlowe. Hero was a virgin priestess of the goddess Aphrodite who Leander saw at a festival, and they fell in love. Leander, using the light Hero placed in the window of her tower, swam the Hellespont night after night to be with her. One night, during a storm, the light went out and Leander drowned. When Hero saw his lifeless body, she drowned herself. The images of the two lovers swirl together as one into the night sky to form the constellation of Hero and Leander.

This work is from a series Fernandez titled Night Writing that uses mythology and constellations as subjects. The star holes also provide another function. They are in Braille and spell out the names of the constellations. Fernandez references the secret code “Ecriture Nocturne,” used by Napoleon’s troops to communicate silently in the dark, and it was the inspiration for Louis Brail

“Nocturnal Navigation” (2013) (polyester resin, gold chroming, polished brass rods of variable dimensions) was commissioned by the US Coast Guard for its new headquarters in Washington D.C. The work comprises 300 constellation points, forming a golden star navigation chart on the lobby wall.

The lobby’s large windows provide light that allows the shadows and colors of the sculpture to change daily and seasonally. Fernandez wanted “to convey a poetic aspect of the Coast Guard, by referencing the vastness of the sea and the heroic, epic qualities of celestial navigation.”

In 2017, Fernandez directed her attention to fires that scorched parts of the contiguous United States, Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Samoa, and US territories. The exhibition titled Fire, United States of America consists of several works. “Fire” (2005) (12’ diameter) (8’ threads of Scalamandre silk woven on steel hoops) was made when Fernandez was exploring water and other elements. In 2017, it became an essential element in this exhibition.

At the left side of the gallery is a relief map in charcoal of the United States. Using charcoal to create the images, Fernandez reminds the viewer that charcoal is burnt wood. Each state is represented, and the ghostly shape of Mexico appears on the left side. Around the wall of this gallery, and other galleries that housed the exhibition, Fernandez drew a continuous charcoal horizon line, punctuated by heavy areas of smoke. She spent several days in the gallery drawing this line.

On the right wall is “Fire (America) 5” (2017) (96”x192”x1.25”) one of several large-scale images of “Fire” created with small ceramic glazed tiles. Other works in the exhibition (not shown here) are titled “Charred Landscape.”

More recently, Fernandez has explored the phenomena of earthquakes and hurricanes. In 2020, she began a series of images using the women’s names of hurricanes: Maria, Katrina, Poloma, and Teresita. She began to think more about Latino women, and to delve more into her cultural history, while continuing to explore new materials and respond to the issues of today’s world. Fernadez is a thoughtful and relevant artist whose work is commissioned and recognized internationally.

“What I’m after is a lingering ephemeral engagement, slow, quiet and with enough depth, kinesthetically, to be recalled by the viewers after the work is no longer in front of them.” (Teresita Fernandez)

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Carla Massoni says

Dear Beverly – Thank you for writing this column. I always find it fascinating and learn something new!

But this one was sheer joy for me – what a brilliant creative spirit Fernandez is.

C.