If your birthday is in October, your birth flower is the marigold. This bright, gold to orange flower has been seen as a sign of the sun for centuries, and its significance has been recognized by numerous cultures and faiths. It is a symbol of joy, prosperity, purity, and the divine. It has often been used as an antiseptic and anti-inflammatory, and as a fabric dye and cosmetic. The name comes from the Middle Ages; “Mary’s Gold” was a reference to the Virgin Mary. Marigolds were used as offerings to Mary, instead of gold, by persons who could not afford real gold.

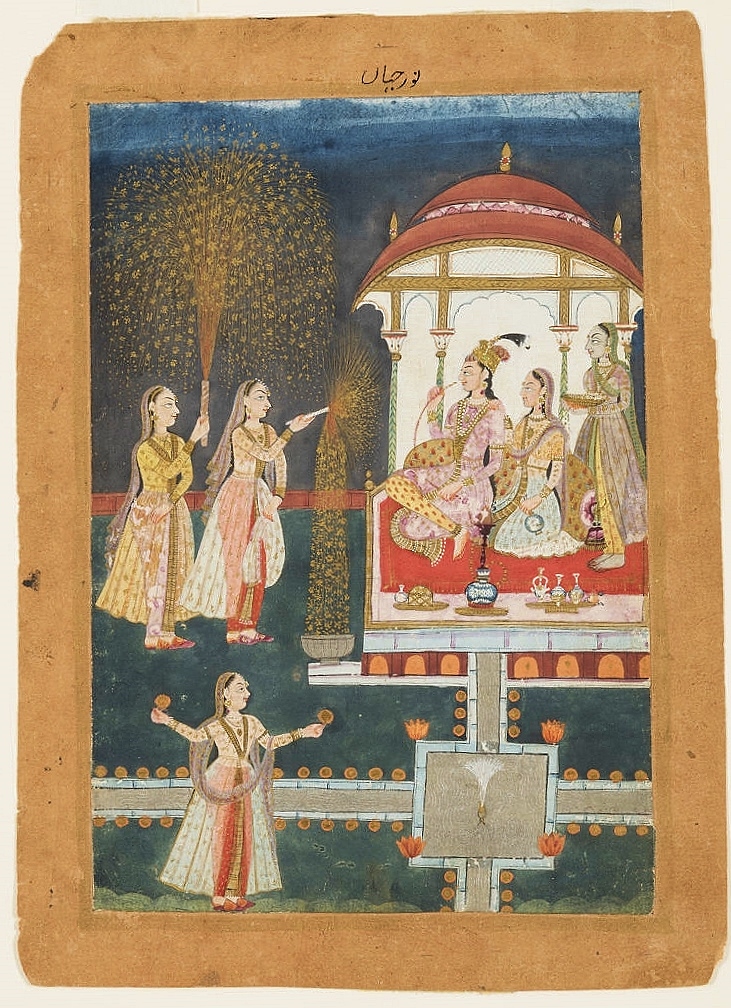

In ancient India, plaques from 300-100 BCE depict marigolds. The Hindu festival of Diwali celebrates the birth of Lakshmi, goddess of wealth and good fortune, but the festival also celebrates the victory of light over darkness, good over evil, and knowledge over ignorance. “Diwali Festival’’ (17th Century) is a page from a Mughal Empire (1572-1858) manuscript. Although Indian manuscripts were small, between four and ten inches, the painters were able to create complex images in great detail. The Diwali Festival was the festival of light; fireworks were a major part of the celebration. The female figure at the bottom of the page holds two marigolds, and the fountain and water channels are lined with marigolds.

Marigolds are hung in garlands on doorways and windows of houses, and they are placed at temples and statues of the Hindu gods and the Buddha. Indians seeking purification in the Ganges River are ringed by marigolds, because they believe purity of the soul can be achieved when one is surrounded by the flowers.

Marigolds are associated with Lord Vishnu and the Goddess Lakshimi, considered to be the ideal married couple. They are plentiful at weddings because of their golden color, cheerful appearance, and positive energy.

There are two major botanical branches of the marigold family: the African and the French. William Morris’s “African Marigold” (1876) (drawing for textile design) used small yellow marigolds interwoven with large lilies and ribbons of acanthus leaves. The design was first manufactured in silk. The “African Marigold” design was printed in several monochrome colors and as seen here in different colors This design caused a rift between Morris and his long-time manufacturer of textiles Thomas Wardle. On February 8, 1881, Morris wrote to Wardle: “I am sorry to say that the last goods African marigold and red marigold sent are worse instead of better: they are in fact unsaleable; I should consider myself disgraced by offering them for sale: I labored hard on making good designs for these and on getting the color good; they are now so printed & colored that they are no better than caricatures of my careful work.” In 1881, Morris built his own factory at Merton Abbey and took over the entire process himself.

African marigolds are the most common form. They were brought to Europe and North Africa by traders in the late 16th Century from Mexico and Guatemala. The flowers grow taller and have larger heads, from two to four inches. In Mexico they play a significant part in the celebration of the Day of the Dead. The flowers are related to grief and death, but also the renewal of life, and are a life force. In 2023, The Day of the Dead is celebrated on November 2.

Swiss artist Felix Vallotton (1865-1925) painted “Marigolds and Tangerines” (1924) (26’’x22’’) (National Gallery of Art, D.C.) the year before he died in Paris. Many artists who survived the horrors of World War I (1914-1918) were forever changed. The Ministry of Fine Arts in France sent Vallotton and two other artists on a three-week tour of the front lines to record the destruction. Their work was presented to the French people in a major exhibition at the Musee du Luxembourg. After this experience, Vallotton concentrated on still lifes of flowers, fruits and vegetables, things that grow. Marigolds are mostly yellow and orange, and in “Marigolds and Tangerines,” Vallotton has chosen the orange French marigold. The tangerines, also bright orange, are symbols of balance, confidence, enjoyment of the moment, and good luck. Whether or not Vallotton knew this, he chose them for the brightness and pleasure he wanted to bring into his life. In these later works, he delighted in the play of light reflecting on the objects. He wrote, “More than ever the object amuses me; the perfection of an egg; the moisture on a tomato; the striking (hammering) of a hydrangea flower; these are the problems for me to resolve.”

For those born between October 23 and November 21, the Native American totem animal is the snake. In Native American cultures, as in many cultures world-wide, the snake can represent either good or evil. For the Navaho, touching a snake would allow an evil spirit (‘chein-dee’) to enter the body. The Cherokee believe snakes have influence over nature, particularly rain and thunder.

From the ancient culture of the Aztecs, the serpent Quetzalcoatl (Feathered Serpent) brought rain and gave maze to the people. A combination of a rattlesnake of the earth and a bird of the sky, it was a powerful symbol. “Quetzalcoatl” (400-600 CE) (Oaxaca) (10.5’’) is one of the earliest depictions found in the city of Teotihuacan from the third until the eight centuries. This early figure wears a headdress of coiling snakes. The annual shedding of its skin links it to rebirth, and to immortality. Quetzalcoatl was the patron of priests because he was said to support and protect them. When the Aztec empire fell, Quetzalcoatl made a journey to the underworld and collected the bones of previous races of the earth and promised to return to allow a new civilization to emerge.

Images of Quetzalcoatl developed into a complex combination of symbols representing the wind, Venus, sunlight, the morning star, merchants, arts, crafts, knowledge, and learning. He also was depicted as a number of animals because he had the power of transformation. Recovering from cancer in Acapulco, the famous Mexican artist Diego Rivera (1886-1957) created a series of murals that tell the life story of Quetzalcoatl. The final image is “Quetzalcoatl” (1956-57) (mosaic). Rivera dedicated his life and his art to his Mexican culture. Quetzalcoatl’s long serpent body consists of a large number of multi-colored feathers extending into a very long tail. His open mouth has large white teeth/fangs and a red forked tongue. A piercing arrow comes from his eye; he sees all and protects. Xoloitzcuintle, a pre-historic hairless dog, walks beside him. A frog, Rivera’s symbol for himself, sits at the lower right corner, holding a flower.

The use of snakes as symbols is visible in the oldest known civilizations. In Egypt, the uraeus cobra in the central element on the Pharoah’s crown, symbolizing the power over life and death given to him by the sun god Ra.

In Judaism, the snake appears in the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. The snake is the devil who temps Eve, who then temps Adam, and thus they are expelled from the Garden. Moses’s staff turns into a snake as a sign of his power from God. The Book of Psalms 74:13-14, tells that God created Leviathan, a giant sea serpent who represents Israel’s enemies, and who only God can slay. Job and the Jews feared this monster, but God broke Leviathan’s head and body into pieces and gave the meat to the people.

Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), who drew “Leviathan” (1908), was a leading book illustrator in England in the 19th Century. Although he did not depict Leviathan as the many-headed monster described in the Old Testament, he created an image of Leviathan that would scare anyone. The large eyes stare out of the exaggerated long face. The mouth is open to show many fangs and teeth, and the long coiling body surges through the water. The viewer can witness the very creative imagination of Rackham. His decision to create a vertical composition and to let Leviathan’s body occupy all of it makes this drawing a powerful and frightening image.

In Crete (pre-Greek), women were not afraid of snakes. They had control over the snake and the powers it was thought to possess. Snakes represented fertility since they come from the earth. They shed their skin annually, representing transformation, the ability to change and adapt, and to be reborn. The “Snake Goddess” (1500 BCE) (carved ivory and gold) (11.5”) is among the many that can be found in the Palace of Knossos on the Island of Crete. Because the statues are small, delicately carved, and made of precious materials, they represent the power of the snake, and the snake is controlled by women.

The theme of women and snakes continued into Greek culture with Medusa, who had hair of snakes. If men looked at her, they turned to stone. When Perseus killed Medusa looking at her with a mirror, Medusa’s snakes were given to the Athena, goddess of wisdom and war. She wore them on her breast plate as sign of her power, but also of her wisdom. Hundreds of paintings and sculptures of the goddess survive from the Greco-Roman through the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

In Buddhism and Hinduism, snakes are called Nagas, and they are a positive symbol. “Buddha Protected by Naga Muchalinda” (c1150 CE) (Cambodia) (sandstone) depicts an important episode in the life of Siddhartha, who would become the Buddha. While the young prince Siddhartha sat in the lotus position meditating under the Bodhi tree and searching for understanding, the demon Mara sent women to tempt him and demons from the sky to harm him. The King of the Nagas, Muchalinda formed a canopy from his body to protect Siddhartha. Muchalinda spreads his snake body with its seven heads over Siddhartha. The Cambodian artist has carved a pattern of leaves from the Bodhi tree between the heads of the snake.

Fans of Harry Potter might recall that Voldemort had a very large cobra named Nagini.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.