I went forest bathing this morning. It refreshed my spirit.

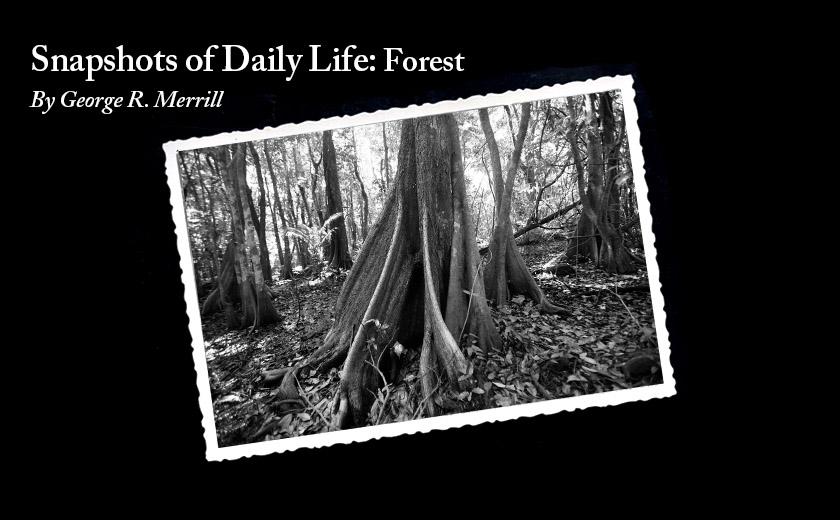

I am in Puerto Rico on holiday. Nearby where my wife and I stay, there is a small Pterocarpus forest on the estate nearby. The forest exists as a preservation effort by the community. An ancient tree native to the island, the Pterocarpus has been known from antiquity to have mystical and medicinal properties. Natives call its sap, ‘dragon’s blood.’

Like taking showers, forest bathing can be hot and steamy, but not here in Puerto Rico. The climate is temperate. Unlike when showering, there are all kinds of critters bathing with me. They are not really bathing; they live here. None seem offended when I bathe. Whenever I come they’re always discreet as we properly expect of others when we bathe –– remaining well out of sight. Salamanders are the exception; they’re voyeurs; they eye me the whole time I undergo my bathing ritual.

I don’t bathe in the conventional sense – buck naked under running water with soap, basically cleaning up. Instead I walk very slowly, fully clad while remaining especially alert. I’m not watchful for fear of predators, but eager to hear messages. You see, the forest speaks, but only in a still small voice. It’s barely audible.

Forest bathing is more ritualistic than any showering or even the legendary Saturday night bath. Every step is intentional. It’s a way of keeping one’s ear to the ground to listen what the forest and its inhabitants are saying.

I begin this bath by sitting on a bench at the forest entrance. The bench overlooks a pond where I see a turtle surfacing. I sit quietly for five minutes. Trees sway in the breeze. A lounge lazily on a grassy patch. He’s sunning himself while a white egret stands close by. Except for trees, everything is still.

I enter the forest, walking on a boardwalk, inches above the dark waters of the swamp. The walk extends three quarters of a mile. The boardwalk sways slightly like a rope bridge. The forest soon swallows me up. The water is dark and filled with detritus. It has a distinctive smell – – dank, a little like the crawl space under my house; this smell is slightly sulphurous, but oddly pleasing. It’s earthy, something like our Eastern Shore’s marshes at low tide.

There are two sounds that prevail as I bathe, both welcoming. One is the soft and hushed cooing of doves and the other, the chirpy and exuberant peeps of the Coqui, the charming little frog that lives on the island. Coquis are often heard, but seldom seen.

All around me the Pterocarpus trees grow, some large, all with their distinctive root systems that extend out from the base of the tree like fans. Natives say the roots look like hens’ feet. The tree gets its stability not by digging in deeper, but by spreading its roots outward into the shallows of the swamp. For enduring stability, reaching out frequently works better than just digging in deeper.

Speaking of reaching out, I see the gossamer threads of spider webs laid across the boardwalk, from railing to railing. There’s one after the other, each about twenty strides apart. If I’m the one that must gently undo their night’s work as I walk by –– I don’t like to –– but I do it as reverently as I can. Putting webs aside tells me I am the first one to walk the forest that day. Not all the forest’s inhabitants welcome forest bathers. We just make more work for them.

Forest bathing is well known to the Japanese. It is one of the ancient practices related to the Shinto religion and today is called ‘shinrin-yoku.’ It’s predicated on knowing that our own healing necessarily connects us to the community of life. Our disconnect from nature today –– inner and outer ––is considered a significant factor in the prevailing ennui that our culture suffers. The phenomenon is beginning to be identified as epidemic. As nature is continually violated in the consumerist culture, there’s a growing awareness of how fundamental our relationship is to nature and how it contributes to our mental health and spiritual awareness.

I think that our casual use of metaphors in language and the images that appear in the decorative arts are drawn mostly from the natural world. Awareness of the depths and beauty of things is expressed in metaphors. Numbers are how the consumerists express their values. In that world, one’s attention must remain focused on the bottom line. The total, however grand it appears, is always one dimensional.

M. Amos Clifford is the founder of the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy Guides and Programs.

He writes: “Forest bathing can have a remarkably healing effect. It can also awaken in us our latent but profound connection with all living things . . . It is a gentle meditative approach to being with nature and an antidote to our nature-starved lives that can heal our relationship with the more-than-human- human world.”

The cellular reaction that vegetation has to our prevailing attitudes and feelings is well established and scientifically verified. Plants don’t like people with an attitude.

My walk in the Pterocarpus forest was not my first. However, it was the first in which I brought attention to all my senses as I bathed my way along its path; the sounds, the smells, the sights, the colors, the shades of light, the scampering critters and the breezes as they rose and fell. I would say that, before I just walked the forest and thought it was a pretty place. I would say this time, by inviting all my senses into the experience, I felt a part of it. I suppose I’m describing that feeling of intimacy and connection that poets describe.

At the end of the path, I walk out of the forest into a clearing. A bench sits there. It’s surrounded by tall Royal Palms. They don’t seem to belong right here. They’re too showy. I take a seat on the bench a few minutes to process my experience. About twenty feet away there’s a huge iguana. He slowly raises and lowers his head, as if performing some form of ancient ritual prayer, exposing a large pelican-like pouch under his neck. He’s a fearsome, primal looking creature, but I take comfort in knowing that iguanas are vegans.

When I took time to listen to the earth that day, what did I hear it say to me?

Come back!

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.

Ginny Davis says

Thank you so much for this. What a gift in this disconnected, trumpian world.

Diane Shields says

Connection to nature – so important to our health, mental and physical. Thank you!

Holly Johnson says

I also love forest bathing. Thank you for sharing.