My mobility has returned slowly, but steadily. I’m now able to do basics, but no quick moves or heavy lifting. I’m pleased.

I’ve had a cane for a while. After the worst of my back ailments, I used it around the house. Then I abandoned it, doing well without it.

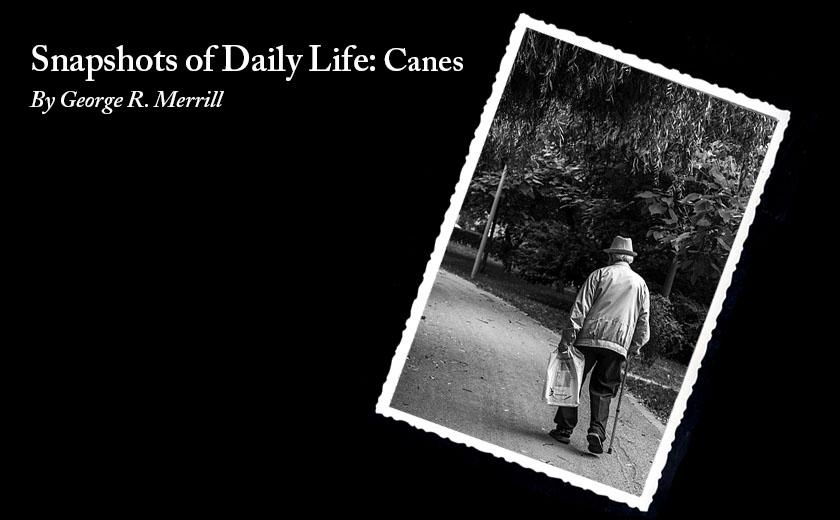

One day, recently, I took an extended walk around my neighborhood. Not being confident of my gait, I considered the practicality of using the cane to avoid falling, but my pride resisted it mightily.

“Why not get into the practices appropriate to the next phase of my life,” I lectured myself half-heartedly. “Consider the cane a kind of warm up for the future.” I only hoped no one would see me. Taking the cane turned out to be a good call, but not without some lessons.

I walked up the driveway out onto the street. I noticed that the cane assisted me in making a surer footing. This increased my confidence. It had been shaken in the last few months. Now, with the cane, I walked longer while experiencing little pain. I was getting into it; placing the cane deliberately to the ground, listening as it struck the ground, tapping rhythmically in synch with my stride; it seemed like a dance. It was neat.

Walking along smartly, I felt proud; wasn’t this like my good old days? Emotionally buoyed, I tucked the cane under my left arm, fancying myself a Marine officer in a movie I’d once seen. He carried a swagger stick. I picked up my pace confidently. I felt jubilant, imperious like a Commander reviewing his troops, the measure of his authority and command resting tidily under his arm. Was he cool, or what? Was I cool, or what?

I didn’t see the rock.

I stepped on it. It turned my foot abruptly. I stumbled just enough to throw me off balance, but not to drop me to the ground. I retrieved my step. Humbled, I returned the cane to its proper use. I’d thought more highly of my new mobility than I ought – or perhaps more accurately, thought of myself as someone I simply wasn’t. I was neither walking in the light I had nor taking the stride that was proper to me.

During this period of my increasing mobility, something else had also been going on within me; the difficulties I experienced in finding my new stride, which I had regarded as limitations for all these months, even humiliations, were not diminishments at all, but another way of being in my world. It was an oblique imperative to slow down and live with increasing awareness of what I was doing in any moment.

Some years ago, I’d done several yoga practices. It was portentous that the walking meditation then was the one exercise that made me the most impatient; it drove me nuts. I was far more of a fidget then. Whether it was walking or doing anything else, I simply wanted to get on with it. I fought against the slow, deliberate measured steps required of the yoga walking meditation. But that’s the only way I can really feel the ground under my feet, the only moments I will ever commune directly with what is always holding me in place no matter what I happen to be about; literally, the ground of my being.

As a younger man, I was an unconscious but willing participant in the frenetic velocity modern culture drives us. I moved quickly, drove fast, walked hurriedly, and wolfed food down – sometimes not even bothering to sit at the table. I answered questions barely taking a breath. I rapidly dispatched anything I was about, getting it out of the way as soon as possible so I could go on to something else. My governor had been stuck for years at full throttle. The challenge to my mental lifestyle began imperceptibly years ago when I first read one of Thich Nhat Hanh’s pithy aphorisms: “When you wash dishes, wash dishes. When you put them away, put them away? I remember reacting to this with a dismissive, “Right, whatever.” However, I never quite shook his thought.

My world view was simple and practical then: dishes were there to be washed and dried and put away swiftly so I could get on with more important things. What was Thich Nhat Hanh getting at anyway?

When I took the cane from the ground, tucked it under my arm and turned it into a swagger stick I lost awareness of where I was my world. I surrendered my alertness to enter an illusory world where I didn’t belong nor ever had I. In the here and now where I walked, my world was in fact right under my feet touching it at every step. Then, too, the more I noticed my steps I also noticed how the ground was strewn with small affirmations of life, past and present. Some were very endearing, like the undulating bodies of the Woolley Bears, executing their tasks of crossing the road to find a place of refuge for the winter.

Others were cryptic. As wind blows hard, Conifer trees broadcast pine needles everywhere and they fall onto the macadam road where I walk. They form curious patterns like Chinese pictograms. The configurations that their thin and supple lines formed demanded my attention, like half completed puzzles. They seemed to express a language of their own as if having left their last habitations on the tree limbs and fallen to earth, and now had a message to communicate to me, something from the life in which they participated as part of the tree. I was a man reading tea leaves.

All very fanciful to be sure except for this: I finally stopped playing soldier that day and got real, and resumed walking with the cane. When I walked, I walked; when I stopped, I stopped; and when I looked at the ground, I looked to the ground and I knew there was no place, at least for those moments, where I wanted to be, except right there where I was.

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.

Phil Hoon says

Cicero once opined that “to live long, live slowly.”