TMDLs are required for any “impaired” waterbody — one that does not meet standards set by a state to ensure a waterbody is safe for people and aquatic life.

A TMDL sets the maximum amount of a pollutant that the waterbody can receive and still meet those standards. The Bay TMDL maximum “loads” are established for the pollutants nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment.

The TMDL, often called the Bay’s “pollution diet,” allocates those loads among the states and major rivers that drain into the Bay. It also establishes specific limits for entities with a discharge permit.

But, in a strict sense, it is not the TMDL that enforces those numbers for individual dischargers. The permits do that job — but they must be consistent with the TMDL.

“TMDLs are not self-implementable,” said Mike Haire, who helped manage the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s TMDL program for years, and now teaches environmental science at Towson University. “But,” he added, “the bottom line is you can’t write permits that aren’t consistent with the TMDLs.” And if water quality standards are not being met after those permit limits are in place — possibly because unregulated sources of runoff are not meeting their goals — the limits “might have to become more stringent than the requirements in the TMDL,” Haire said.

Likewise, rules governing TMDLs do not establish deadlines, they only state that goals should be achieved in a “timely manner.”

But courts have held that water quality standards are to be met “reasonably promptly,” and the Bay cleanup could face a court-imposed deadline if the effort continues to fail, said Ridgeway Hall, an environmental attorney who has worked on Bay issues and written about its TMDL. (See the related article, MD threatens to sue EPA, PA over lack of action as regional tensions rise.)

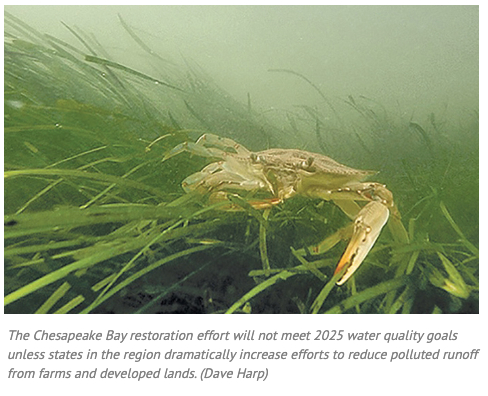

While the Bay TMDL sets limits as all TMDLs do, it has several unique aspects. It includes an “accountability framework,” developed by the EPA and the states in the Bay watershed that goes beyond what TMDLs traditionally require. The framework includes a 2025 cleanup deadline that was agreed upon by the state-federal Bay Program partnership in 2007.

The accountability framework also requires states to write plans showing how they will meet cleanup goals, setting two-year milestones to provide “reasonable assurance” that they will meet their goals. Those milestones were suggested by the states.

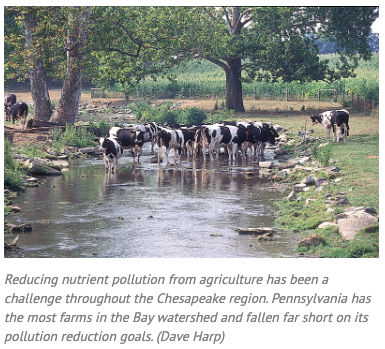

The TMDL also outlines steps the EPA can take if states fall short of their goals for reducing pollution, including unregulated discharges from sources such as farms. Those “consequences,” such as forcing further reductions from regulated sources, are grounded in the EPA’s authority under the Clean Water Act.

“The contingency actions were set up to get people’s attention and to recognize that there is a limited set of actions that the agency can take under the Clean Water Act,” said Rich Batiuk, retired associate director for science with the EPA Bay Program Office and a key architect of the Bay TMDL. “If states want to control their own destiny, we are saying great, but you need to hold up your end of the bargain or there is a price to be paid,” he said.

The Bay TMDL is also unique because its goals were adopted into the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement signed by the EPA and Bay states.

Section 117g of the Clean Water Act, which creates the state-federal Bay Program, includes a requirement that the EPA administrator “shall ensure that management plans are developed and implementation is begun by signatories to the Chesapeake Bay agreement to achieve and maintain … the nutrient goals of the Chesapeake Bay agreement …”

In terms of TMDL authority, “I think 117g presses EPA into a different place than other TMDLs in other places,” said Jon Mueller, vice president for litigation with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

Don’t miss the latest! You can subscribe to The Chestertown Spy‘s free Daily Intelligence Report here.