State environmental regulators are taking legal action against the owners of a closed paper mill in Western Maryland, alleging that it is continuing to pollute the North Branch of the Potomac River.

State environmental regulators are taking legal action against the owners of a closed paper mill in Western Maryland, alleging that it is continuing to pollute the North Branch of the Potomac River.

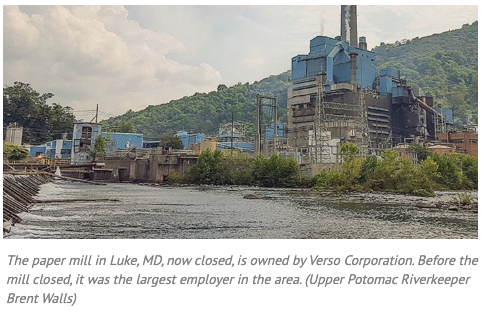

Verso owns the Luke paper mill in the Allegany County town of the same name, though part of the facility also lies across the river in Beryl, WV. The mill closed in June 2019, ending 131 years of operation and eliminating 675 jobs.

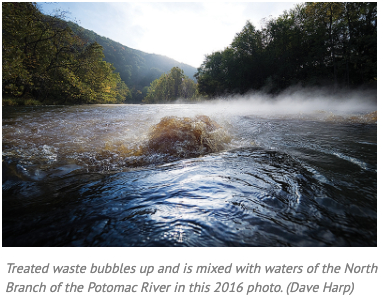

In April, before it shut down, a fisherman reported seeing “pure black waste” in the North Branch near the Luke mill, according to Frosh’s announcement. Inspectors found black liquid seeping from the riverbank into the water.

According to the lawsuit, the substance appeared to be “pulping liquor,” a corrosive and caustic byproduct of the papermaking process. Samples of the seepage detected elevated pH and low dissolved oxygen levels, the state filing said. The samples also were high in sulfur and sodium. Industrial safety data on pulping liquors indicate they can burn skin or eyes on contact and may also irritate the respiratory tract if inhaled in mist form.

The Maryland Department of the Environment ordered Verso to find the source of the discharge and take steps to stop it. The company installed sump pumps to collect the black liquid as it seeped from the riverbank, but regulators received complaints about continuing discharges in the summer and fall. Samples taken in late October had an alkalinity similar to household chlorine bleach.

On. Nov. 4, according to the lawsuit, West Virginia’s Department of Environmental Protection ordered Verso to empty its above-ground storage tanks on that state’s side of the river, saying it was violating storage tank laws. The company then piped those tanks’ contents across the river to tanks in Maryland, the lawsuit contends.

MDE’s lawsuit says it directed Verso to post signs on the riverbank near the seepage warning people not to drink or have contact with the water because of the presence of hazardous materials. The company posted signs saying “Restricted Area, Do Not Enter,” but would not post signs with the warning language specified by MDE, the lawsuit says.

MDE’s lawsuit says it directed Verso to post signs on the riverbank near the seepage warning people not to drink or have contact with the water because of the presence of hazardous materials. The company posted signs saying “Restricted Area, Do Not Enter,” but would not post signs with the warning language specified by MDE, the lawsuit says.

Kathi Rowzie, Verso’s vice president for communications and public affairs, said that “we continue to work cooperatively and transparently with both Maryland and West Virginia regulatory agencies to address concerns at the facility.” She said the company is conducting a subsurface study ordered by MDE and has emptied all of the liquor tanks and other vessels near the river seeps.

A consultant that Verso hired to investigate the seeps found pulping liquor in the ground near the seeps, even though the plant was shut down and the tanks emptied. The consultant’s report submitted to MDE did not call for further investigation and did not spell out a plan for stopping the seepage.

“After numerous attempts to get Verso to comply with Maryland’s environmental laws, the company continues to allow pulping liquor to contaminate the river, harming fish and wildlife, in violation of Maryland’s laws,” Frosh said in a statement.

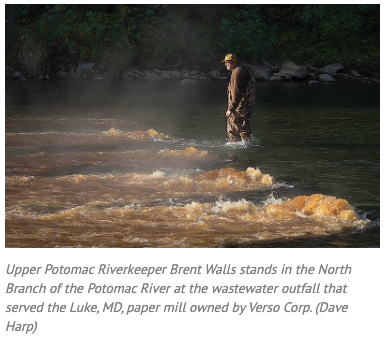

The state lawsuit comes almost a month after the Environmental Integrity Project, on behalf of the Upper Potomac Riverkeeper, notified Verso of its intent to file a federal lawsuit against the company for discharging toxic material, which it contended was black pulping liquor, coal ash or both.

In its lawsuit, MDE asks the court to order Verso to halt the seepage of pollution into Maryland waters and post warning signs on the river about the risks of exposure to the discharge. It also seeks civil penalties.

In its lawsuit, MDE asks the court to order Verso to halt the seepage of pollution into Maryland waters and post warning signs on the river about the risks of exposure to the discharge. It also seeks civil penalties.

But Brent Walls, the Upper Potomac Riverkeeper, questioned why the state suit makes no mention of the coal ash he contends may also be leaking into the river. There’s a coal storage facility on company property just upriver of the apparent black liquor seeps, he said, and there was evidence there of some discolored leakage as well.

In the group’s Nov. 19 letter to Verso, the Environmental Integrity Project said sampling done by the Potomac Riverkeeper Network detected toxic constituents of coal ash, including arsenic and mercury. Walls said he was concerned that the substances he alleges are being discharged could interact chemically and convert the mercury to a form that builds up in fish tissue and could pose health threats to any angler who eats contaminated fish taken from the river.

In late November, MDE spokesman Jay Apperson said that the state’s inspections determined that the impact of the seep is localized and that water quality remains good downriver. On Tuesday, when asked why coal ash was not mentioned in the state’s lawsuit, Apperson said MDE’s investigation is continuing.

By Timothy B. Wheeler

Don’t miss the latest! You can subscribe to The Chestertown Spy‘s free Daily Intelligence Report here.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.