A healthy Chesapeake Bay means a healthy economy, and a full recovery cannot be accomplished without a strong, bipartisan federal commitment. That commitment includes respecting states’ rights under the Clean Water Act.

A healthy Chesapeake Bay means a healthy economy, and a full recovery cannot be accomplished without a strong, bipartisan federal commitment. That commitment includes respecting states’ rights under the Clean Water Act.

Section 401 is the single most powerful authority granted to states under the Clean Water Act. It establishes a unique “certification requirement” that allows states and authorized tribes to impose preconditions on, or block, certain types of federally issued permits and licenses. This certification requirement applies to any entity applying for a federal license or permit for “any activity” that “may result in a discharge” into waters of the United States.

Currently, states have one year to issue or deny a water quality certification for a project requiring a federal permit. Backlash from industry groups, particularly members of the fossil fuel industry, against the 401 process has prompted punitive action by the federal legislative and executive branches. Their complaints fall into two camps: delays in issuance of federal permits and licenses, and purported abuse of section 401 by states that take into account other impacts beyond water quality.

In April, Sen. John Barrasso, R-WY, reintroduced S. 1087, the Water Quality Improvement Act of 2019. The bill would require states to make final decisions on whether to grant or deny a request in writing based only on water quality reasons and require them to inform project applicants within 90 days, regardless of whether the state has all of the materials necessary to process a request. In August, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed a rule to replace its original section 401 regulations with a version that substantially pares back state authority.

This coordinated attack on state authority in the guise of clarification is unnecessary and unwanted. The Supreme Court has found that states have significant latitude under the Clean Water Act, including the ability to condition certification upon any effluent limitation or other appropriate state law requirement to ensure the facility will not violate state water quality standards.

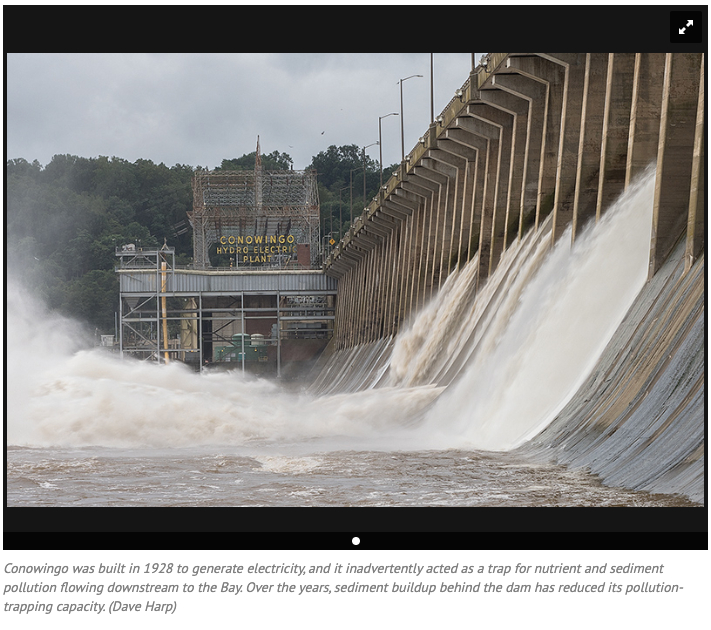

The section 401 process plays an important role in the ongoing relicensing of the Conowingo Hydro Electric Project. The owner of the dam, Exelon Generation, originally applied for a water quality certification in 2014, but withdrew it after Maryland state officials said they did not have enough information on the water quality impacts of the dam. The company resubmitted its application in 2017. In October, the state and Exelon reached a settlement at the one-year mark on the reapplication. Exelon agreed to spend $200 million over 50 years on projects to rebuild eel, mussel and migratory fish populations in the Susquehanna River and to reduce nutrient and sediment pollution flowing down the river into the Upper Bay.

Reaction from stakeholders to the settlement has been varied. Some praise the agreement’s provision for pollution reductions upriver from the dam. Others support the investments to restore filter feeders such as mussels and fish passage for their symbiotic partner, the American eel. (The larvae of certain freshwater mussels [called glochidia] attach to the gills of eels to hitch a ride upstream.)

Some riverkeepers feel the deal does not go far enough to address the dam’s impacts. In addition to questioning the amount Exelon had agreed to spend, others still worry the agreement lacks detail in places and assurances that Exelon will be held to its commitments.

The proposed settlement is not perfect. But it might not exist at all without section 401. It certainly would reflect less of a consensus had negotiators been allowed only 90 days — just three months, as the proposed legislation would require — to strike a balance between a number of complex needs for the project: electricity, restoration and even recreation.

And the settlement is not the end of the story. We have more work to do upstream — Exelon, Maryland, other watershed states, the federal government and other stakeholders. At the federal level, we are working to secure — and increase — funding for the EPA Chesapeake Bay Program that in recent years has redoubled its efforts to target funding to areas within the watershed where the water quality bang for the buck is highest.

As part of that effort, Sen. Chris Van Hollen and I in September announced the award of almost $600,000 in competitive funding for grantees to carry out planning, financing strategy and monitoring projects for the Conowingo Dam reservoir through the Chesapeake Bay Program. These federal resources will help develop a road map to offset the impacts of the reservoir’s reduced storage capacity, which has resulted in increased pollutants making their way through the dam and into the Chesapeake Bay. Establishing a Watershed Implementation Plan specifically for Conowingo, similar to the plans being written by each state and the District of Columbia to clean up the Bay, highlights how essential addressing the problem is to restoring and protecting the health of the Chesapeake.

Finding solutions to address such complex problems is not easy. The federal government must not make the water quality certification process even harder by putting its thumb on the scale for industry. For now, our states are not required to confine themselves to the impacts of the discharge itself, but can address a range of conditions as part of their certification: physical and biological impacts such as water withdrawal from a river or habitat impacts.

I am deeply concerned the Barasso legislation — and more urgently the Trump administration’s regulations it has inspired — will deprive states of the leverage they need to secure commitments to protect water quality. Maryland has joined many other states, Republican– and Democratic-led, in objecting to those proposed rules. The rule-making follows a disturbing pattern: Where partisan proposals are stopped in Congress for lack of bipartisan support, the Trump administration carries the torch, forging ahead in disregard of thousands of public comments in opposition.

This effort must not succeed, or the Chesapeake Bay will suffer for it.

The views expressed by columnists are not necessarily those of the Bay Journal.