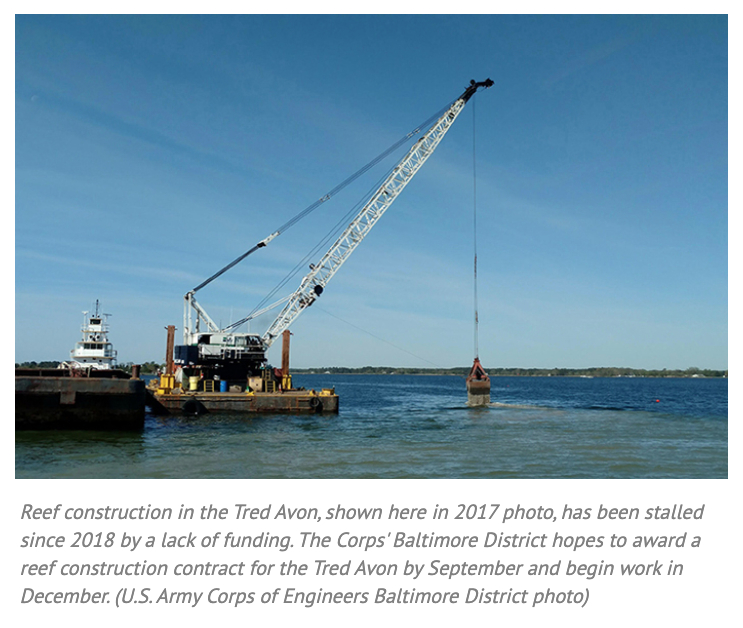

The money, included in the annual workplan that the Army Corps submitted on Monday to Congress, is designated for oyster restoration work in Virginia as well as Maryland. But the Corps’ Baltimore District said it plans to use most of the funds to complete reef construction in the Tred Avon, one of an extensive network of sanctuaries in Maryland off limits to harvest.

That work, begun in 2015, aims to restore 147 acres of oyster habitat in the Eastern Shore river. The Corps and its state, federal and nonprofit partners have restored about 85 acres so far at a combined cost of $5.9 million. They have planted a total of 440 million hatchery-spawned seed oysters on new or existing reefs, where the bivalves are left alone to grow and reproduce, help clean the water and provide habitat for fish, crabs and marine creatures.

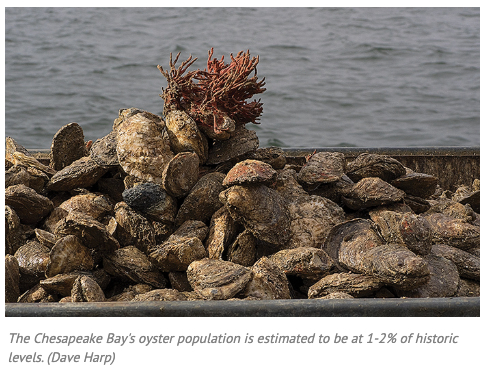

The Tred Avon is one of five Maryland waterways targeted for large-scale oyster restoration. With Bay oyster populations depleted to 1% or 2% of their historic abundance by pollution, overfishing and disease, Maryland and Virginia have each pledged to rebuild oyster populations and habitat in five of their Bay tributaries by 2025.

Restoration work has been completed so far in just one of Maryland’s tributaries, Harris Creek. Nearly 2.5 billion hatchery-spawned oysters have been planted there on 350 acres of restored reef, at a cost of more than $28 million. Work is nearing completion in the Little Choptank River and is planned for the St.Mary’s and Manokin rivers. Restoration has also been completed in just one of Virginia’s five tributaries, with work under way or planned in the others.

But the Tred Avon project, paid for primarily with federal funds, got hung up early on by disputes over the materials and methods the Corps used to rebuild oyster reefs. More recently, it has been virtually stalled by a lack of Corps funding to complete it.

For about two decades, the Army Corps regularly received funding to build oyster reefs in the Bay. But the flow of money ended in 2016, shortly after Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan’s administration asked the Corps to halt work in the Tred Avon.

The holdup was prompted by some watermen objecting to the use of granite to build reefs in the Tred Avon and in Harris Creek. They complained that granite reefs snagged crabbing gear and that improperly constructed granite reefs in Harris Creek were damaging boats.

The watermen also argued that reefs should be replenished exclusively with oyster shells. They contended that those are the only suitable surface on which spat, or baby oysters, can settle and grow.

Research has shown, however, that oyster spat will do well on other hard surfaces in the water, and monitoring of the granite reefs built so far in Maryland has found oysters in great numbers on them, and even at higher densities than on reefs rebuilt with shells.

The Hogan administration later lifted its hold on the Tred Avon project, and work resumed in April 2017. But further delays and cost overruns ensued because of the state’s insistence at that time that no more granite be used in the reef construction. By the time the state withdrew its objections, federal funding from past budgets had been depleted.

Some restoration advocates have said the disputes factored in the loss of funding for Corps reef construction work in the Bay. In the last few years, the Hogan administration has joined with Maryland’s congressional delegation in pressing the White House to restore that funding, without success.

Appeals also have been made to the Corps to use some of its discretionary funding to revive reef construction in the Bay. Last year, in approving the fiscal year 2020 federal budget, Congress called for the Corps to put toward oyster restoration some of the unallocated money it received. The Corps did so in the work plan it submitted to Congress Monday.

The Corps needs to build about 40 more acres of reefs in the Tred Avon to reach the minimum 125-acre threshold needed to consider the restoration project complete. The Baltimore District hopes to award a construction contract by September and begin work on the reefs in December, said spokeswoman Sarah Lazo.

The oyster restoration money is part of an $18.2 million infusion of funds to the Corps Baltimore District for work not specifically listed in the federal budget for fiscal year 2020, which ends Sept. 30. Also included are $1.9 million for the restoration of seven miles of stream habitat in the Anacostia River watershed and $500,000 to continue planning to restore vanishing James and Barren islands with sand and silt dredged from shipping channels in the Bay.