Synagogue El Transito (1355-57)

The city of Toledo had eleven synagogues during its golden age. Today only two of the synagogues remain. Last week’s SPY article touched upon the Ibn Shoshan Synagogue/Santa Maria le Blanca (1180). The Synagogue of Samuel ha-Levi/Synagogue El Transito, on the Calle Samuel Levi, dates from 1355-57. It was a private home and yeshiva (school). Samual ha-Levi held the positions of chamberlain, treasurer, judge, and councilor to the Christian King Pedro of Castile. The Jewish ha-Levi family had served the Christian Castilian House of Burgundy since 1200. The family included one of the last Jewish poets in Spain who wrote in the Arab style during the 12th and 13th Centuries.

As can be seen in the photograph, the size and height of the Synagogue exceeded the height restrictions applied to synagogues. It is taller than the two-story buildings across the street. King Pedro may have given permission to deviate from these restrictions in appreciation for ha-Levi’s work for him. The designer was master mason Don Meir Abdie, one of the King’s architects and builders. The synagogue was annexed to the ha-Levi palace.

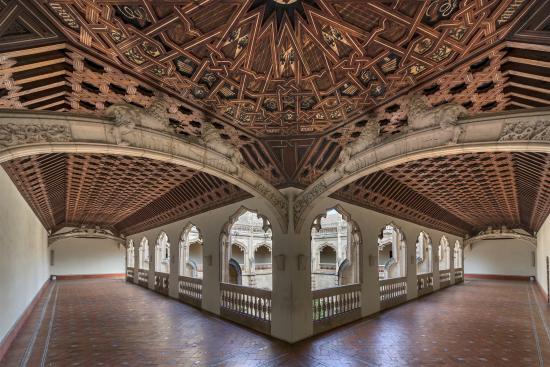

Synagogue El Transito (interior)

The prayer hall was 76 feet long by 30 feet wide and 40 feet tall. Along the upper wall are large frames of larch wood with floral patterns of inlaid carved polychrome and ivory. Only a section of the original mosaic floor is preserved. The women’s gallery with five openings can be seen at the right of the southern wall.

The wooden ceiling is composed of joined beams, interlaced with supporting rafters. The decoration of the square in the center represents the stars of heaven. The vegetal designs in the floor mosaics represent earth. Together they represent the close connection of heaven and earth. The designs are a reference to the city of Jerusalem and Temple Mount, the highest point in the city, where King Solomon built the First Temple. Stucco decoration and inscriptions reference the Jewish people’s desire to return to Jerusalem.

At the present time, the Temple Mount is the location of the Al Aqsa Mosque, and it is closed to Jews. The only section of the old temple Jews can access is the western retaining wall, known as the Wailing Wall.

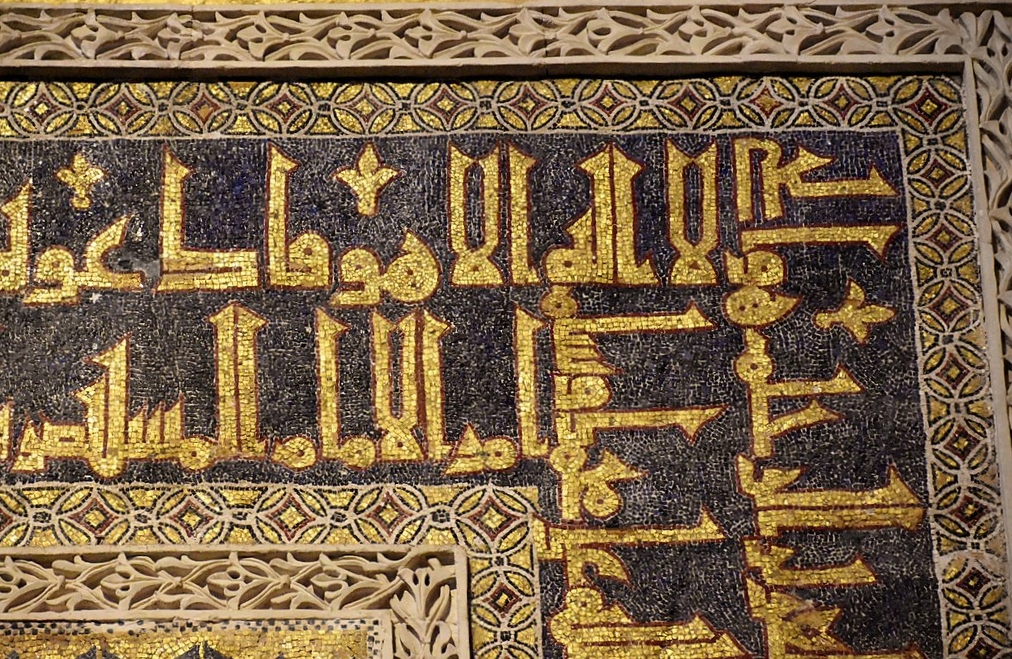

Torah Niche

The Torah niche, on the eastern wall of the synagogue, has three multi-lobed arches. It is decorated with plants, family symbols, and interlacing designs. The inscriptions are carved in Kufic, the Arabic script, and include text praising the King and text from the Book of Psalms. Samuel ha-Levi was also praised: “The exalted pious prince of princes of the tribe of Levi…has exceeded in all deeds by building a house of prayer for the Lord God of Israel…and he commenced building this house in the year 1357.”

Upper Wall (detail)

Elaborate carving continues around the upper wall. ha-Levi imported cedar beams from Lebanon for the construction. The cedars of Lebanon famously were used by King Solomon in his construction of the First Temple. The delicate leaf and flower interlacing is punctuated with family crests. The horseshoe arches are multi-lobed. The gold mosaic text is set against dark blue mosaics. The iron window grills, popular in Mudejar buildings, were a unique feature that added to the eloquence of their structures.

Window Grill (detail)

Castile and Leon Coat of Arms

The inclusion of King Pedro’s coat of arms illustrates his esteem for ha-Levi. He was trusted with the seal of the King. Text is placed under the coat of arms: “See the sanctuary now consecrated in Israel, And the house which was built by Samuel with a pulpit of wood for reading the law, With its scrolls and its crowns all for God. And its lavers and lamps to illuminate, And its windows like the windows of Ariel.”

King Pedro was criticized by his rivals for his tolerance of the Jews. He finally turned against ha-Levi, accusing him of embezzlement. He was put into prison in 1360, and he died there from torture.

When all Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, the synagogue was converted to a Catholic church, El Transito (Assumption of the Virgin), and it was given to the Order of Calatrave. Restoration of the synagogue began in 1879. It had been declared a National Monument in 1877. It was officially established as the Museo Sefardi in 1964. In 1968, its official name became the National Museum for Hispanic-Hebraic Art, and it remains so today. The museum section adjoining the synagogue includes a garden in which contemporary Jewish sculpture is displayed.

Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes (1477-1504)

Across the road from El Transito is the Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes (1477-1504), built by Isabella and Ferdinand and dedicated to the birth of their son Juan and their victory over Alfonso V of Portugal at the Battle of Toro (1476). However, it remains unclear who won the battle. The Queen ordered the placement on the walls rows of manacles and shackles that were worn by the Christian prisoners who were held by the Moors and Africans in Granada and later freed by the Reconquista.

Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes (detail of chains)

Monastery of San Jaun de los Reyes

The monastery church was built in the Catholic Gothic style (pointed arches). The walls were constructed of cream-colored limestone. Throughout there are sculptures of saints, animals, and plants. The most repeated sculpture is the coat of arms of Isabella and Ferdinand held by an eagle, the icon of St John. Napoleon’s troops occupied the monastery and set it on fire. The church and one cloister remained standing. Restoration began in 1883 and was completed in 1967

Monastery of San Jaun de los Reyes

The lower level of the cloister walk was decorated with images of saints, fantastic beasts, and temptations. Isabelle and Ferdinand had the upper level constructed with a ceiling in the style of the Mudejar, which continued to be popular among the Catholics. The upper level included a ceiling of larch wood. Geometric carvings included coats of arms, lions, arrows, and other symbols of Spain. When the Muslims and Jews were driven from Spain, an exception was made for the Mudejar master craftsmen.

Upper Level of the Cloister (detail)

The Golden Age of Spain series will continue with Seville and the Alhambra in Granada.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.