Autumn began on Sunday, September 22 this year. In Greek mythology, Persephone, the daughter of the goddess of the harvest Demeter, had returned to live in the Underworld. She had been abducted in the Spring by Hades, God of the Underworld. In response, Demeter stopped everything from growing on Earth until she found out where her daughter had been taken. She appealed to Zeus and Aphrodite on Mt Olympus and a bargain was reached. Persephone would live in the Underworld for half the year and with her mother on earth for the other half. This myth explained why they Earth was bountiful in Spring and Summer, and barren in Autumn and Winter.

“View of Mt Washington from North Conway, New Hampshire” (1860-65)

“View of Mt Washington from North Conway, New Hampshire” (1860-65) (14”x19’’) was painted by Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902). He was born in Germany but immigrated with his parents to New York when he was two. As an artist, he was a member of the Hudson River School. He went on several expeditions to explore the western territories to California. Bierstadt always was interested in representing the seasons and the time of day in his work. An avid outdoorsman, he also found opportunities to include animals in his painting. Fall foliage dominates this painting, with three cows quietly drinking from the lake, and Mt Washington’s peaks clearly visible in the distance. The setting is a calm Autumn day with no rain, no rainclouds, and no wind. All of Bierstadt’s paintings were landscapes, and all evidence his strong feelings for the America’s landscape.

“Autumn Oaks” (1873)

“Autumn Oaks” (1873) (21”x30’’) by George Innes (1825-1894) represents work during the middle of his career. Born in Newburgh, New York, he became interested in art at an early age. He studied at the National Academy of Design in the mid-1840s, and traveled to Europe and was inspired by French art from the 17th Century through the Barbizon school of landscape painting. He was member of the Hudson River School. “Autumn Oaks” is typical of his middle style with dramatic clouds and strong coloring. Innes’s autumn trees range in type and color from fiery orange, bright yellow, and green turning to brown. Cattle graze, with a bull in the foreground watching over them. A farmer is harvesting hay in the field at mid-ground. Sunlight streaks across the scene in several places and draws the viewer’s attention into the distance. Threatening dark clouds roll in, while five white birds fly through the clouds. Innes has caught the intensity of colors that precede an Autumn storm.

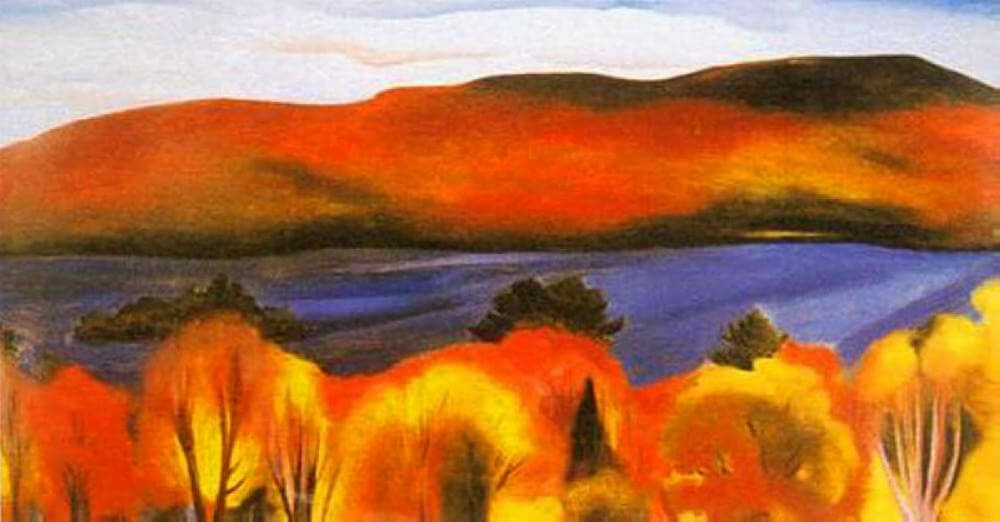

“Lake George, Autumn” (1927)

“Lake George, Autumn” (1927) (17”x32”) is by Georgia O’Keeffe. She and Alfred Stieglitz spent the Summer and Fall seasons at the family estate in Lake George, New York, from 1918 until 1934. The 36-acre estate was located by a 30-mile glacial lake. She had her own studio where she could paint in peace and quiet. Georgia painted several scenes of Lake George. “Lake George Autumn” was a departure from her usual approach, because she eliminated the lake shore and included only the essentials. A practice she continued for the rest of her career. Her painting approaches the abstract with the use of bold color shapes for the autumn trees, the deep blue for the glacial lake, and the bold orange for the distant mountains.

In a letter in 1923 to the writer Sherwood Anderson, O’Keeffe described her emotions concerning her work: “I wish you could see the place here–there is something so perfect about the mountains and the lake and the trees. Sometimes I want to tear it all to pieces–it seems so perfect–but it is really lovely–and when the household is in good running order–and I feel free to work it is very nice.”

“Fall Plowing” (1931)

“Fall Plowing” (1931) (24’’x39’’) is by Iowa born painter Grant Wood (1891-1942). He was one of three American Regionalists, including John Steward Curry and Thomas Har Benton, whose style was popular from the 1930s until the1940s. The panoramic scene begins with a walking plough and a steel ploughshare, used by Midwestern farmers at that time. Plowed fields are ready for new planting. Already harvested fields and wheat stacks cast shadows across already harvester fields. Simply designed yellow and orange Autumn trees are dotted over the landscape of rolling green fields that lead to a small red barn and white farmhouse. The composition is formed by diagonals that are painted with simple hard edges. The day is sunny. Regionalism became popular in the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl in the 1920s through the mid1920s. The three midwestern artists wanted to illustrate life on their beloved prairie, with its good and bad aspects.

“Fall Plowing” hangs in the John Deere headquarters in Moline, Illinois. John Deere, a blacksmith from Grand Detour, Illinois, invented in 1938 the walking plough made of molded steel. At that time, the farmers rejected the metal plough because they thought the metal would reduce the fertility of the soil, encoumraging growth of weeds. Wood’s painting illustrates that farmers came to use and appreciate the metal plough.

“Corn Shocks in October Sunshine” (1954-59)

“Corn Shocks in October Sunshine” (1954-59) (30”x40”) is a watercolor by Charles Burchfield (1893-1967). Born in Ashtabula, Ohio, Burchfield was an American modernist whose paintings reflected his sensitivity to nature: its sights, sounds, colors, times of day, and seasons of the year.

He assimilated all these images into his own vision of nature. This watercolor depicts not only three corn shocks but also the yellow and white energy radiating from the field and the corn shocks. Two ears of corn and three blue flowers are placed in the foreground to create a triangular composition. Green is repeated on the flowers and on the edge of the distant road. Hazy fields lead to distant trees and sky. Burchfield keeps viewers’ attention on the grain stacks. He recorded his thoughts in a daily journal: “An artist must paint not what he sees in nature, but what is there. To do so he must invent symbols, which, if properly used, make his work seem even more real than what is in front of him.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.