Of the hundreds of women scientists, why am I highlighting these two? One reason is they contributed in areas that hold great interest for me, astronomy and biology, disciplines at opposite ends of the size scale. The other is that they died early (of cancer) and thus became ineligible for the Nobel Prize which by rule cannot be awarded posthumously.

Of the hundreds of women scientists, why am I highlighting these two? One reason is they contributed in areas that hold great interest for me, astronomy and biology, disciplines at opposite ends of the size scale. The other is that they died early (of cancer) and thus became ineligible for the Nobel Prize which by rule cannot be awarded posthumously.

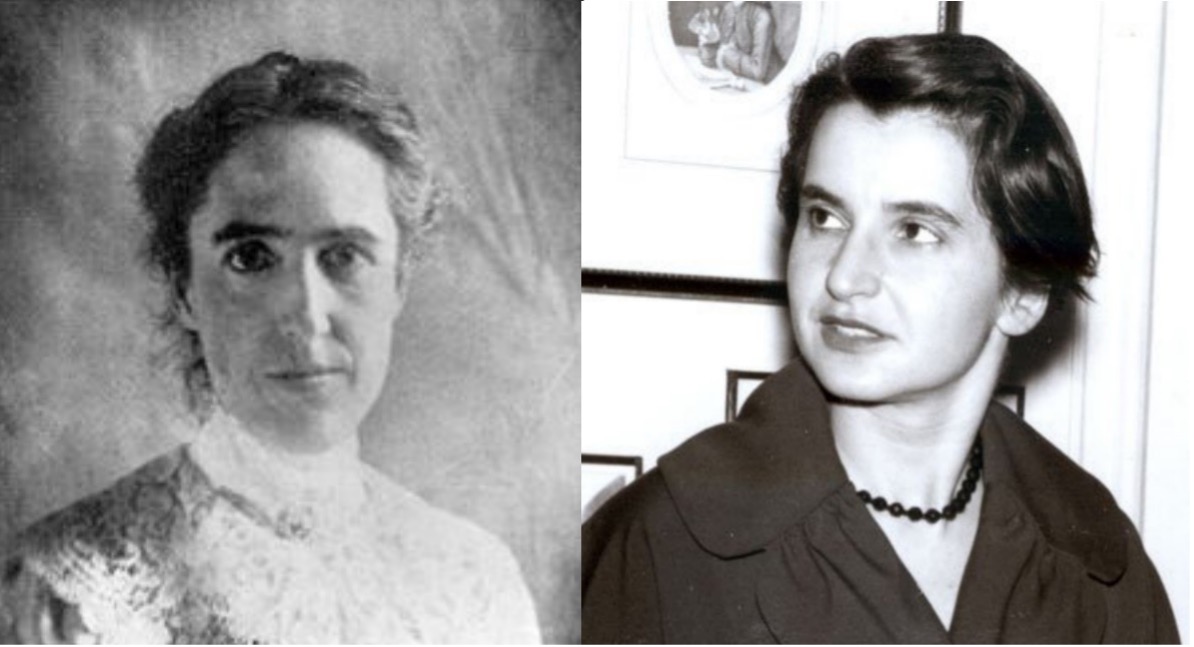

Henrietta Swan Leavitt (1868-1921) was an American astronomer. A graduate of Radcliffe College, she worked at the Harvard College Observatory as a “human computer”. In 1902 the director of the observatory, Edward Pickering, assigned her to measure and catalog, from the observatory’s collection of photographic plates, variable stars in the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds, nebulae thought to reside within our own Milky Way galaxy.

By graphing the magnitude (apparent brightness) versus logarithm of period of variable stars called Cepheids, Leavitt discovered that “A straight line can be readily drawn among each of the two series of points corresponding to maxima and minima, thus showing that there is a simple relation between the brightness of the Cepheid variables and their periods.” In short, the brighter the star, the longer was its period of oscillation. Her results were published in the Harvard College Observatory Circular of 1912.

Logarithms compensated for the property of light called the “inverse square law”, whereby apparent brightness decreases as the inverse square of its distance. For example, given two sources of equal absolute brightness (say two 100-watt bulbs), if one is three times farther away than the other, it will appear one-ninth as bright.

Ms. Leavitt brilliantly concluded that Cepheid variable stars could serve as the long-sought “standard candle” which would allow measurement of distances well beyond the currently accurate, but relatively short-ranged, triangulation method called stellar parallax.

Apparent brightness, absolute brightness, and distance are related by a simple equation. Knowing any two of these three variables will yield the third. But in 1912 not a single Cepheid variable star had had its distance accurately measured. Thus, Leavitt’s chart could not be calibrated (and used) until the distance to at least one Cepheid was known.

That problem was solved one year later when Ejnar Hertzsprung, using parallax, determined the distance to Delta Cepheus and several other Cepheids in our galaxy. Leavitt was then able to say that the Small Magellanic Cloud was 100 times farther away than Delta Cepheus and was in fact another galaxy.

“Leavitt’s Law”, along with Vesto Slipher’s discovery of spectrographic redshift, allowed Edwin Hubble to discover that our universe is expanding. He often said that Levitt deserved the Noble Prize for her work.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt (Isn’t that a wonderful name for an astronomer?) died of stomach cancer at the age of 53. Asteroid 5383 Leavitt is named for her, as is Crater Leavitt on the Moon.

Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958) was a British chemist and X-ray crystallographer whose work led to the discovery of the structure of DNA. A graduate of Newnham College, with PhD from Cambridge University, she was hired in 1950 by John Randall and assigned to work with Maurice Wilkins at King’s College London in trying to discover the structure and replicating mechanism of the DNA molecule.

Franklin had made herself an expert in X-ray crystallography, even suggesting design improvements of the instrument. However, images produced by X-ray crystallography are anything but lucid. It’s akin to shining a light up through a crystal chandelier, photographing the image you see on the ceiling, and from that deciding what the chandelier looks like – a lot of interpretation required.

Franklin and Wilkins did not get along. Wilkins thought Franklin was hired to be his assistant; Frankin thought she was hired as his equal.

In 1952 two other teams were competing to be first in discovering the structure of DNA, thought to be the copying mechanism of genetic material and recipe for building every living thing. James Watson and Francis Crick were working at the famous Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge, 60 miles north of London. Linus Pauling, who a year earlier had discovered, using X-ray crystallography, the alpha-helix (single helix) structure of proteins, was working at Caltech in the USA.

Watson and Crick collaborated well, and somewhat with Wilkins at King’s College, but not with Ms. Franklin who did not trust that the guys would ultimately give her credit for her work.

To give you a feel for the environment that Ms. Franklin had to endure I present the following quotes by James Watson from his book The Double Helix; A Personal Account of the Discovery of THE STRUCTURE OF DNA (1968).

“By choice she [Rosalind] did not emphasize her feminine qualities. Though her features were strong, she was not unattractive and might have been quite stunning had she taken even a mild interest in clothes. This she did not. There was never lipstick to contrast with her straight black hair, while at the age of thirty-one her dresses showed all the imagination of English blue-stocking adolescents.”

“Clearly Rosy had to go or be put in her place. The former was obviously preferable because, given her belligerent moods, it would be very difficult for Maurice to maintain a dominant position that would allow him to think unhindered about DNA.”

Franklin was meticulous in analyzing data and the X-ray images she had her assistant, Raymond Gosling, take. It was obvious that DNA had a helical form, but was it a 2, 3, or 4-strand helix? And were the nucleotide bases on the inside or outside of the phosphate groups that formed the “rails” of the helical ladder?

Watson and Crick thought they knew, as they had been building physical 3-D models of various configurations. Hoping for confirmation, Watson went down to King’s College and asked Rosalind if he could view her latest images. In the presence of Wilkins, she refused, saying she had not had time to analyze them. She stormed out of the room, apparently upset that Watson would even ask. Her feelings toward him must have been reciprocal. Watson then asked Wilkins if he could see Franklin’s images, and Wilkins agreed! An egregious breach of ethics in scientific research.

James Watson, in seeing famous “Photo 51” (Google it), immediately recognized the double-helix structure of DNA. On 28 February 1953, at the Eagle pub on the Cambridge University campus, he and Crick announced that they had “discovered the secret of life.”

Watson, Crick, and Wilkins were awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Rosalind Franklin had died of ovarian cancer at the age of 37 in 1958, and so was ineligible to receive the Nobel Prize she rightly deserved.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.