Edward Mitchell Bannister (1828-1901) was born in New Brunswick, Canada. His parents were Edward Bannister of Barbados and Hannah Alexander of Canada. After their deaths, Edward and his younger brother lived on the Ontario farm of the wealthy lawyer and merchant Henry Hatch. Bannister attended an integrated school in Canada. His interest in art was stimulated by copying art in the Hatch home. He and his brother emigrated to American and settled in Boston in 1840. They worked on ships as mates and cooks. By 1850 they were working as barbers, giving them status as middle-class professionals.

“Rhode Island Seashore” (1856)

Bannister desired to be an artist, but his mixed-race status prevented him from attending art school. He was self-taught: “Whatever may be my success as an artist is due more to inherited potential than to instruction…All I would do I cannot…simply for the want of proper training.” Nevertheless, his talent was recognized; he received his first commission in 1854 from the African-American Dr. John V. DeGrasse “Rhode Island Seashore” (1856) (17.5’’x22’’) is one of the earliest extant Bannister paintings. His love for the sea coast and Rhode Island landscapes was his constant subject, and it proved very popular. The panoramic view of the seashore includes sand, sea, waves, rocks, green lawn, a dock, two people walking at the edge of the waves, and several holuses nestled among trees under a light filled sky. He was influenced by the French Barbizon landscape painters. The canvas shows his mastery of the media and the subject matter.

“Oak Tree” (1876)

Bannister married Christina Carteaux (1819-1902), of African and Native American descent. She was a well-known hairdresser and wig maker. Christina was an entrepreneur who owned several hairdressing establishments. Her substantial income allowed Bannister to become a full-time painter by 1870. They settled in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1869. Bannister credited her with much of his success: “I would have made out very poorly had it not been for her, and my greatest successes have come through her, either through her criticisms of my pictures, or the advice she would give me in the matter of placing them in public.” Bannister received national recognition when “Under the Oaks’’ (1876) (location unknown) won first prize at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition.

”Moonlight Marine’

“Oak Tree” (1876) (34’’x60’’) (Smithsonian American Art Museum) is thought to be similar to his first-class prize winner, and it is the standard comparison used today. Bannister landscapes evoked the things he loved about the New England countryside. The male figure with the fishing pole, walks down the path toward the row boat. Bannister often depicts cows grazing in a field. The entire panorama pays attention to local flowers, distinct types of trees, and an interesting distant landscape.

The award for “Under the Oaks” caused controversy. Bannister submitted the painting anonymously as “Number 45,” with only a signature. Banister wrote, “I was and am proud to know that the jury of award did not know anything about me, my antecedents, color or race. There was no sentimental sympathy leading to the award of the medal.” He described the experience when he entered the exhibition hall to claim his prize: “As I jostled among them, many resented my presence, some actually commenting within my hearing in the most petulant manner: What is that colored person in here for?” At the judge table, he was ignored until he told them who he was. “[A]n explosion could not have made a more marked impression. Without hesitation he apologized to me, and soon everyone in the room was bowing and scraping to me.” Some wanted the award to be rescinded, but they were overruled.

Bannister purchased the sloop yacht Fanchon in the 1880’s, and spent his summers painting and sailing from Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, to Bar Harbor, Maine.

“Moonlight Marine” (1885) (22”x30’’) is an example of Bannister’s continued love of the sea and the various moods of nature. The prosperous shipping industry along the coast gave him ample opportunity to paint dramatic seascapes in daylight, or as in this case, at night. The moon, surrounded by hazy clouds, provides just enough light to see the silhouette of the distant ship and to light the breakers that crash against the rocks in the foreground.

Hay Gatherer’s” (1893)

From 1876 onward, Bannister received many commissions, won medals, and exhibited widely. He was one of the co-founders of the Providence Art Club (1880), the third oldest art club in America. It was the first to admit women. The Club remains active today.

Bannister did not submit work to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in1893. The paintings would be pre-judged before they were sent to Chicago. From his experience with an1885 exhibition at the New Orleans Cottom Exhibition, Bannister knew his work would be segregated, and ignored. Bannister and his wife were extremely active in the abolitionist movement. Although they were well known for participating in many abolitionist projects, he did not carry this theme into his paintings. “Hay Gatherers” (1893) (18”x24’’) is an exception. The figures in this landscape are African-American field workers. Art historians speculate that the setting could be the South Country Plantation, Rhode Island’s largest plantation, and where Bannister’s wife was born. Regardless of the location, the painting depicts his later style which trended toward Impressionism. The brush strokes are more suggestive than realistic, the atmosphere is moist. The day is hot and long.

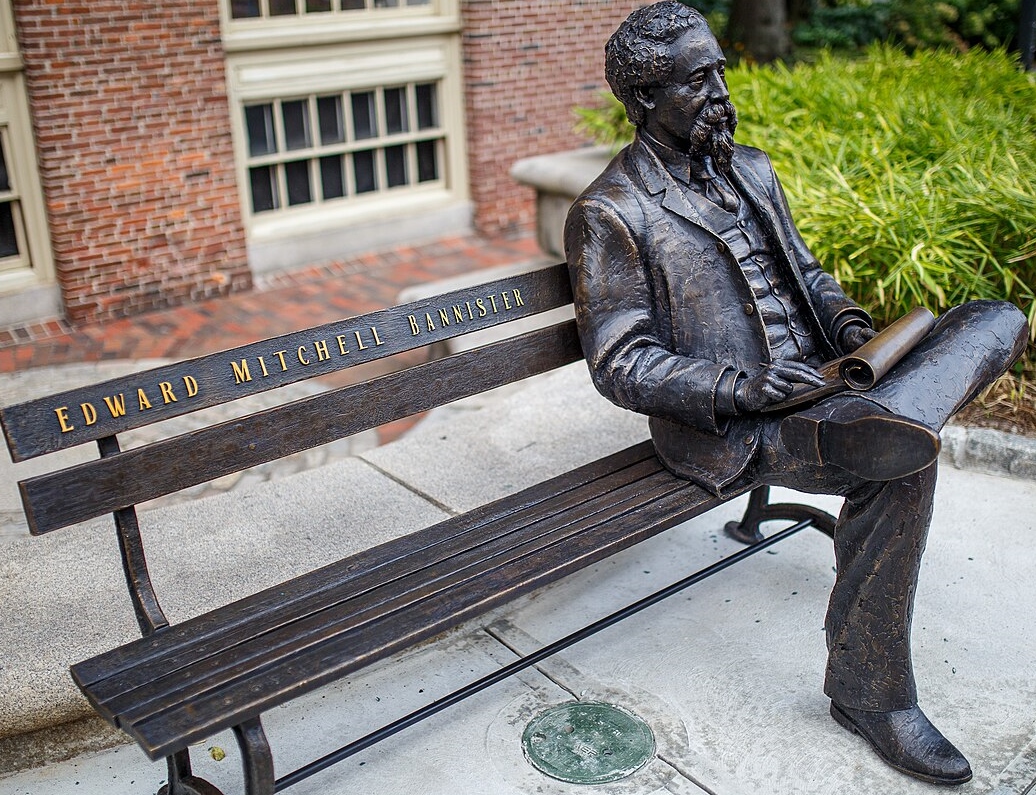

Edward Mitchell Bannister statue, Market Square, Providence Rhode Island

Bannister suffered a heart attack on January 9, 1901, during an evening prayer meeting at his church, the Free Baptist Church. His wife and their extensive circle of friends, black, white, and members of the Providence Art Club, held a memorial exhibition in 1901. “His gentle disposition, his urbanity of manner, and his generous appreciation of the work of others, made him a welcome guest in all artistic circles…He painted with profound feeling, not for pecuniary results, but to leave upon the canvas his impression of natural scenery, and to express his delight in the wondrous beauty of land and sea and sky.” (Exhibition pamphlet)

The Civil Rights movement of the 1960s generated new interest in Bannister’s work, in both his painting and his role in the abolitionist movement. Several exhibitions of his work have been held, and his work can be found in several museums. Many of his paintings are now in the Smithsonian American Art Museum collection in Washington. DC. Magee Street in Providence, originally named after a Rhode Island slave trader, officially was changed to Bannister Street in 2017 to honor Edward and Christina Bannister. The bronze sculpture “Edward Mitchell Bannister” (2023) (Gage Prentiss, sculptor) was placed in Providence’s Market Square in September 2023.

“I have been sustained by an inborn love of art and accomplished all I have undertaken through the severest struggles.” (Edward Mitchell Bannister)

Note: During the Civil War, Bannister painted a portrait of Robert Gould Shaw, commander of the African-American 54th infantry regiment. Bannister and his wife organized a fair to raise funds to pay the Massachusetts African-American 54th, 55th, and 5th calvary regiments, who chose to go without pay for 18 months, rather than take less than white soldiers. Among other causes, Christina Carteaux Bannister founded a home for Aged Colored Women in Providence for house servants who became too old to work, and who often died alone and in poverty.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.