As a resident of the historic district of Chestertown for seventeen years, and as one who has had a long interest in and has written about the Black history of the town, county, and state, I am writing to you with regard to the application before the Historic District Commission for the construction of a house at 206 Cannon Street. There are two matters relevant to this application that, to my knowledge, have been raised only briefly and that I think could be helpful to the HDC in their discussions of the proposal. First is the instruction to the HDC found in the Code of Ordinances for the town (Chapter 93-8) and posted on your website, which states that “In reviewing applications, the Commission shall give consideration to the historic, archeological, or architectural significance of the site or structure and its relationship to the historic, archeological, or architectural significance of the surrounding area” [emphasis mine].

The second matter is the grant of fifty thousand dollars that the Maryland Historical Trust has received from the Department of the Interior’s Historic Preservation Fund. This grant is designated specifically for Chestertown, for the purpose of “updat[ing] the Chestertown National Register Historic District to reflect its full, diverse history.” The press release for the project notes that “the Town of Chestertown has an incredibly rich Black history, yet this story is not reflected in the National Register of Historic Places, our nation’s official list of places worthy of preservation.” My understanding from an officer of the MHT is that the staff of the project will begin collecting information in mid-February and that they expect to be able to issue a full report on their findings within a year.

The priority that the MHT has given to Chestertown indicates that it has found our town remiss, since its placement on the National Register, in failing to make Black history a part of decisions about how to preserve the special character of the town—in spite of the injunction in the Code of Ordinances to do so. The Governor of Maryland, Wes Moore, has just announced (on January 19, 2024) the award of five million dollars in grants from the Maryland Historical Trust and the African American Heritage Preservation–one of which went to our local library to restore and preserve the former African American funeral home that is now on the library property. In his announcement, the Governor noted that “African American history is American history and Maryland history—and we have a solemn duty to preserve it and learn from it.” The MHT is clearly acting in complete accord with the Governor’s priorities in turning its attention to the history of Black Chestertown.

It should be useful to the HDC to have the findings of the Trust before them in making future decisions, especially decisions about properties that lie within a historically Black section of the town. The HDC might want to delay any further decisions about the Cannon Street property until the relevant sections of the Trust’s study are available. In the short term, I believe the HDC would benefit from having further information about the scope of the Trust’s study, its procedures, and its specific timeline. It should be possible to find this information quickly. It also seems appropriate, in light of the two matters raised in this letter, for the HDC to begin its own, independent consideration of the relevance of Chestertown’s Black history to the plans for the property at 206 Cannon Street.

The site connects two areas included in the Historic District: (1) Scott’s Point, an area of almost twenty acres, including the waterfront and portions of Cannon Street, South Water (Front) Street, and South Queen Street (Railroad Avenue), and (2) the Cannon Street corridor between Queen Street and Mill Street. Both of these areas have historically been the site of extensive Black residences and businesses. The free Black population of Chestertown in 1850 was approximately 350; by 1870, the Black population had increased to just over 800, making the town more than 43% Black. Many—probably most—of this Black population lived in these two areas. They also worked in a succession of businesses in Scott’s Point: a sawmill, a fertilizer company, a basket factory, a canning factory, a fishery, and others. The property at 206 Cannon was for a while home to a lumber yard and a coal yard; residents of Scott’s Point and the Cannon Street area reported that their children delighted in playing on the coal piles. It was a wonderful place to grow up, reported one Black resident, adding that families in the area took care of each other, especially of the children. More study is needed to document the demographic and physical changes in the area (which seems to have no Black residents at this time), especially at Scott’s Point, in places such as the densely populated “Boardwalk” section of Railroad Avenue (now South Queen Street), where wooden walkways were once necessary for crossing the marshy ground.

Beginning as early as 1825, Black entrepreneurs began operating their own businesses in both the Scott’s Point and the Cannon Street areas. A rough estimate of the number of Black businesses operating in this small part of the Historic District between 1825 and 1865 indicates that there were more than twenty-five. Many of these were restaurants and oyster bars, but there were also barber shops, an ice house, butcher shops, a hotel on South Queen Street, owned by Peter Jones, and a store on South Queen Street owned by Henry Phillips, a former slave. These businesses prospered in spite of opposition from many whites in the town, including the writer of a letter to the Chestertown Transcript, who urged his fellow townsmen to patronize only white hotels and oyster houses instead of those kept, as he asserted, by “’colored citizens,’ whom the destructives and political abolitionists have attempted to place on a footing with the white man, and they are still endeavoring to extend greater privileges, instead of legislating them to Liberia or some other clime.”

In spite of this kind of opposition, by the middle of the nineteenth century, the number of Black residences and businesses in the Cannon Street corridor had increased considerably; until at least the 1950s, this area was home to primarily Black residents. It was also home to one of the most prominent Black churches on the Eastern Shore, Janes United Methodist Church. Founded as Zion Methodist Episcopal Church of the Colored People of Chestertown in 1831, it originally occupied a building in the 200 block of South Queen Street. The land for the church was donated by Thomas Cuff, a black businessman who owned several properties on Queen and Front Streets. The church relocated twice and has stood on Cross Street since 1914; the new church was built with bricks made by members of the congregation. Bishop Edmund S. Janes, for whom the church was later named, called it the “flagship” Black church of the area. In 1865 George B. Westcott donated an acre of his land for a burial ground for the church; it was apparently located in what is now Wilmer Park. When the park was formed, the plan was for the graves (and bodies) to be relocated to a new cemetery on Quaker Neck Road; the full story of that plan has not yet been told.

Cannon Street between Queen and Mill Streets continued until recently to be populated by Black residents and studded with Black businesses. Former residents of the street, still living, recall a number of black-owned businesses operating on the street in their lifetimes. These included three barber shops, two beauty salons, a laundry, two taverns, a bar, a candy store, a dairy store, a small church, a restaurant, a snack bar, the Commodore Electric company, and a printing company. Tellingly, none of these businesses exists today.

The historic GAR building, home of the Charles Sumner Post #25, Grand Army of the Republic, is just off Cannon Street on South Queen Street; its property adjoins the property under consideration at 206 Cannon. The post was established in 1882 by twenty-one Civil War veterans who had served in the U.S. Colored Troops. The current building was constructed around 1908. It is now one of only two GAR buildings known to survive in the United States and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. When the last of the original members of the GAR died in 1928, the building, which became known as the “Army Hall,” continued to be used as a gathering place for meetings, weddings, and concerts.

The GAR Hall was the site of a celebration of the Fifteenth Amendment (giving Black men the right to vote) in May, 1870, three months after the ratification of the amendment. The celebration drew an estimated crowd of three thousand celebrants from Chestertown and surrounding communities. (A delegation from Centreville managed to arrive safely, after being followed from Centreville to Church Hill by a group of Klansmen who shouted threats and threw stones at them.) A procession of two hundred and fifty decorated wagons, bands, and mounted troops marched from the Hall through Chestertown and gathered at a spot outside of town to hear speeches from several speakers, including Chestertown native Henry Highland Garnett.

The GAR also honored veterans annually on Decoration Day (the predecessor of Memorial Day). In 1883 the celebrants marched to Janes Church cemetery and decorated the graves of five Black veterans of the Civil War; they then marched to Chester Cemetery and decorated the graves of all the deceased soldiers known to be buried there, regardless of race. The celebrations of Decoration Day continued until the late 1920s.

One of the founding objectives of the GAR was, according to its records, to keep Americans reminded of the role of the GAR in reuniting a divided nation. The challenge of reunion was addressed by a number of Black citizens of Chestertown living in what is now the Historic District, who played a significant role in making their town and their state a less divided and more democratic place. They succeeded in spite of consistent and sometimes vicious white resistance. Chestertown had passed a town ordinance in 1868 that restricted the right to vote to white males who owned property, thus disenfranchising a large percentage of the town’s population. The conservative Democrats of the town, who were strongly opposed to the Black franchise, found a property-owner willing to sell off one hundred one-foot-square parcels “lying in a three-foot alley,” according to the Elkton newspaper, to one hundred buyers promising to vote Democratic. When the fifteenth amendment was ratified in February of 1870 (Maryland voted against ratification), the governor of Maryland, in order to stave off federal interference, quickly vetoed Chestertown’s requirement that voters must be white, although he did not veto the property requirement.

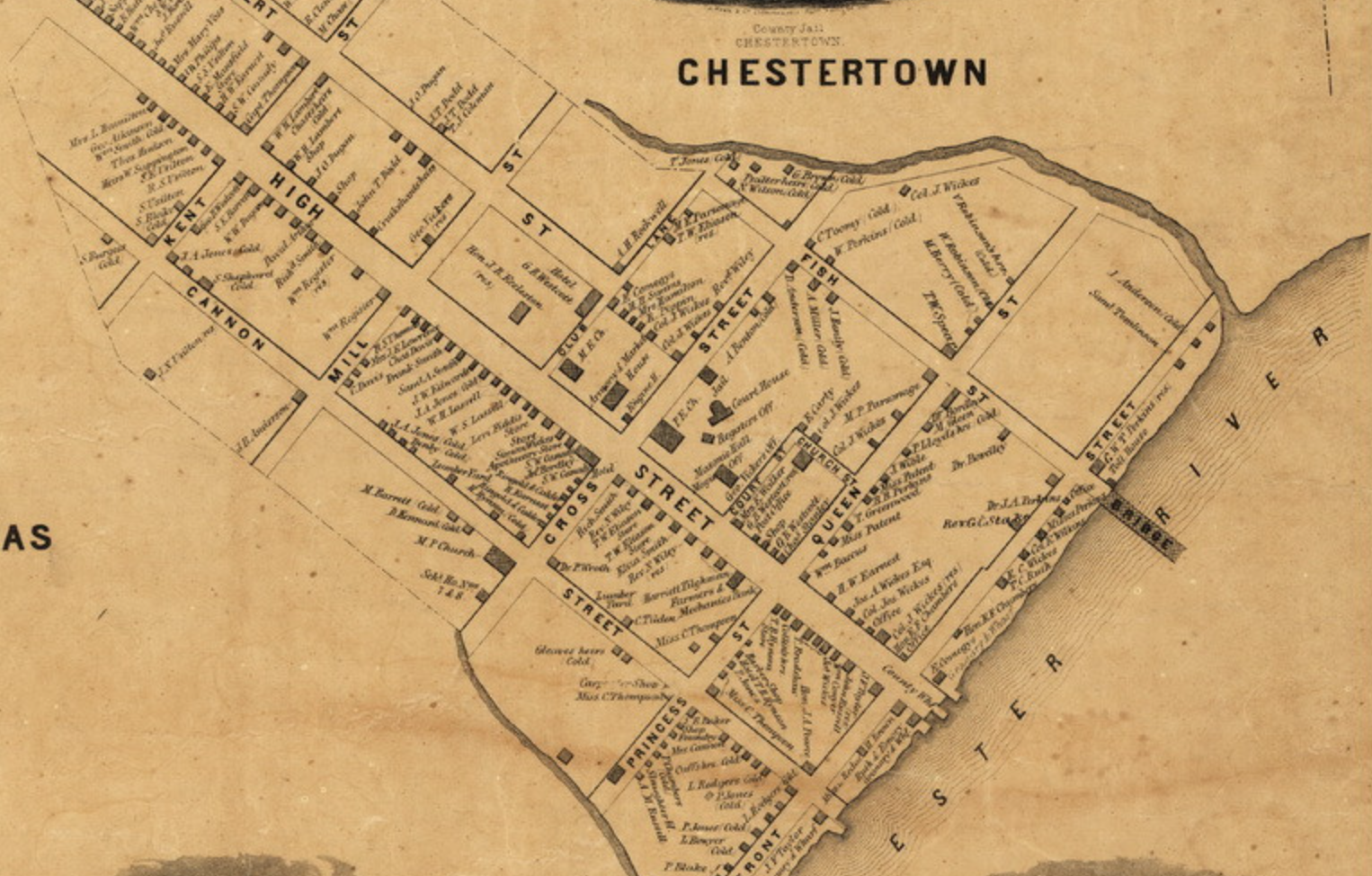

There were Black property owners in the town at the time. The 1860 Martenet map of Chestertown identifies twenty-nine Black property owners in “Chestertown proper.” Of these, twenty-one owned properties that now included within the historic district, on Cannon, Queen, and Front Streets. They were still, however, a minority of the property owners, and they were much less affluent. By 1870, the combined assets of the 10 wealthiest whites was $1,362,800; the combined assets of the ten wealthiest Blacks was $3,300.

Black leaders in Chestertown responded to the efforts to deny their right to vote; Isaac Anderson sold a plot of land, three feet, nine inches by thirty-four feet, adjacent to his home on Water Street, to forty-four Black men. Other sales followed, by James A. Jones and others. In 1871, Jones sold lots of one square foot to fifty Black men—for five dollars. Significantly, these lots lay at the edge of Jones’s property on Cannon Street and adjoined the property of John Denning, a Chestertown native who, like his father, had spent his career as a slave dealer. In the first town election held after the ratification of the fifteenth amendment, the Republicans, bolstered by the addition of about one hundred and fifty new Black land-owning voters, won the election for town commissioners by twenty-two votes. Anderson, Jones, Richard T. Jones, and others continued to sell their small lots to Blacks until at least 1877.

Before the election, the Chestertown Transcript had carried an advertisement for a Democratic journal that existed primarily, if not solely, to advance the argument that “white men must rule America.” The Transcript had also warned that the object of the Republicans was the “Africanizing” of the whole state and that a Republican win would mean “negro equality in public conveyances, hotels, theatres, public schools, courts, and juries. It means absolute negro domination. White men, are you ready for it?” After the Republican win in the election, both Chestertown newspapers called the election a fraud that presaged the day when “the white man will be as good as a n*****”; they labeled the Republicans a “mongrel party.” It was a small-town vote and victory, but it was recognized as important well beyond the town and the state; the story was told in the New York Times and in the newspapers of many other places around the country, including Buffalo, Philadelphia, Vermont, Kansas, Ohio, and Delaware.

The real significance of this victory, which had its origins in the determination of the Black people of Scott’s Point and the Cannon Street area, was explained in a 1994 article for the Maryland Historical Magazine (written by a University of Maryland law professor, C. Christopher Brown). Titling his essay “Democracy’s Incursion into the Eastern Shore,” Brown pointed out that while Black voting went smoothly on the Western Shore after the fifteenth amendment, things were different on the Eastern Shore: Black voters were turned away from the polls in many places, including Salisbury, St. Michaels, and Easton. The Chestertown election was truly historic, he pointed out, not only because these were the Eastern Shore’s first Black voters but because “the setting for this historic event was the Shore’s wealthiest town.” Chestertown, Brown wrote, brought democracy to the Eastern Shore.

It matters that the property at 206 Cannon Street lies squarely between the Scott’s Point and Cannon Street areas, both of which have histories as important as those of any other areas in the Historic District, and both of which need much further documentation. They also need, I believe, to remain linked, physically, as they clearly are in their histories and their legacies.

Thank you for reading and for your consideration.

Sincerely,

Lucy Maddox

Ph.D., English, University of Virginia, 1978

Board of Directors, Kent County Historical Society, 2010—2014

Board of Directors, Friends of Miller Library, Washington College, 2012—2015

Chestertown Historic District Commission, 2013—2015

The People of Rose Hill: Black and White Life on a Maryland Plantation, Johns Hopkins Press, 2021.

The Parker Sisters: A Border Kidnapping, Temple University Press, 2016.

Citizen Indians: Native American Intellectuals, Race, and Reform, Cornell University Press, 2005.

Editor, Locating American Studies: The Evolution of a Discipline, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999 (Translated and reprinted in Korean, 2000.)

Billie says

Thank you for this very thorough history of Chestertown.

While I am not a resident of Chestertown, I sincerely hope that the Historic Commission will take its content into serious consideration while debating the current issue as well as any future development in town.

Tess Jones says

Well said. Thank you for sharing this history, Lucy.

barbara S vann says

Thank you so much for this concise but very informative history of the black Chestertown community. Clearly, we need to value the area and its rich history. Your points are so well taken and indeed the proposed building for that site would be a grave injustice.

Bettye Walters says

Thank you so much for this very informative history lesson. It shows how important historical events are to today’s Chestertown.

Bill Barron says

Eye-opening and nicely written. Thanks for your very well detailed and objective work.

Mary Ellen says

Thank you !

Lynn Mitchell says

Well done, Lucy! A fascinating and important consideration in the upcoming decision by the HDC.

Mary Ann Moran says

Dear Ms Maddox,

At the very least this was eye opening!

I appreciate the richness of your words on many levels.

Best,

Mary Ann Moran

David A Turner says

Lucy, as always your material is insufferably well researched. You didn’t quite make a final point re. the proposed mansion to be built on Cross Street. I’d be interested in your opinion if you have one. Chestertown’s historic district is a jewel and continues to surprise me.

Roberta Hantgan says

This is a truly amazing research report. Thank you for sharing it. Any chance you would teach a lifelong learning class on the history of black Chestertown?