In the last speech he delivered in Memphis the night before he was assassinated, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. recalled his Birmingham, Alabama nemesis, segregationist commissioner of public safety Bull Connor, siccing dogs and fire hoses on civil rights marchers. King proclaimed: “There was a certain kind of fire that no water could put out. And we went before the fire hoses; we had known water. If we were Baptists or some other denomination, we had been immersed. If we were Methodist and some others, we had been sprinkled, but we knew water.”

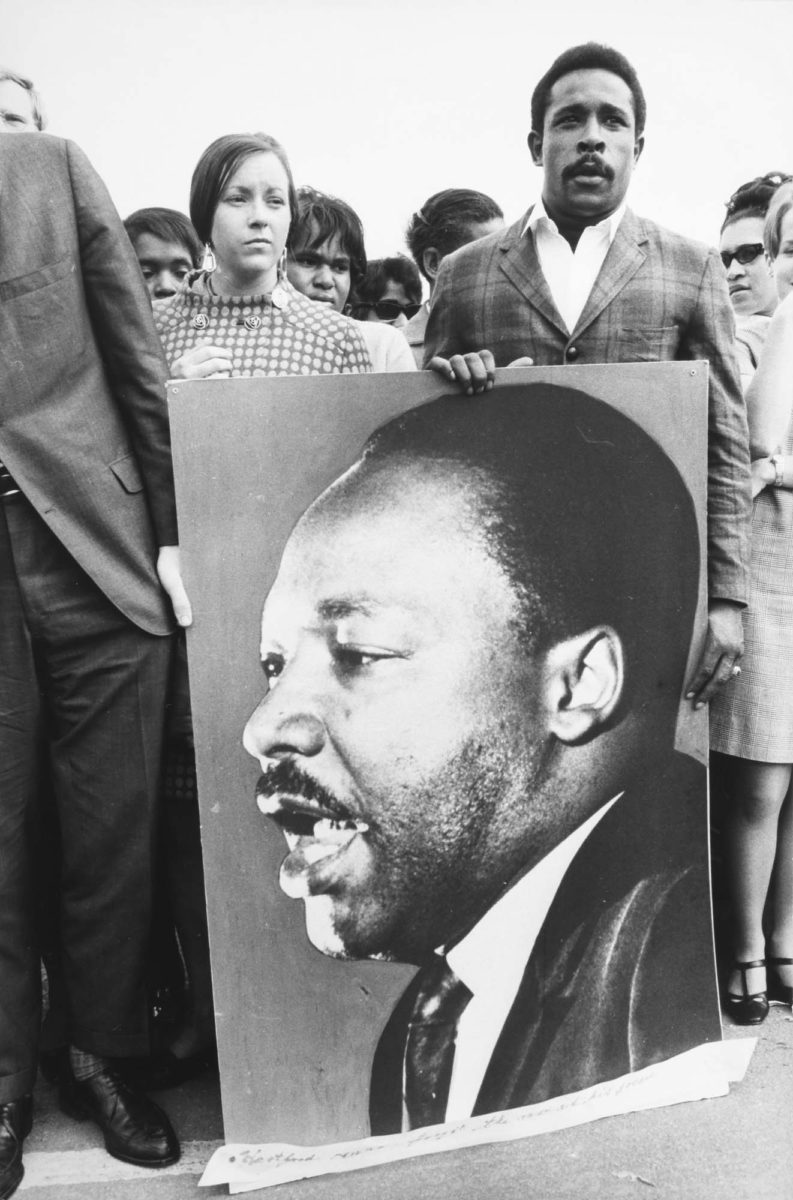

Approaching a half-century after his April 4, 1968, murder, Atlanta’s High Museum of Art mounted a photographic testimonial to the authenticity of the nonviolent civil rights movement launched by King. I say “authenticity” because so much of what is fact and history today is questioned by those who would have us erase the reality that many African Americans who may or may not feel disadvantaged today are the progeny of those who were captured, transported across the Atlantic, and sold into slavery. Book banners and others seek to conceal parts of history that reflect poorly on the American dream, saying they want to spare young white people any hint of guilt or shame. But no one is blaming white children or adults, generations removed from the slave trade in America. But the truth still matters. And always will.

The exhibit that opened at Easton’s Academy Art Museum in this 55th year since the Rev. King’s murder records the struggle for justice by African-Americans who, especially in the South, never escaped the enforced disenfranchisement of Jim Crow “laws” rolling back the Civil War Proclamation of Emancipation.

Upon entering the AAM’s Lederer Gallery, we see Burk Uzzle’s black-and-white photo of black Americans attending a march for striking sanitation workers in Memphis, where King showed up in support. Three blocks away, Uzzle also photographed white men lined up along the strikers’ march route. Meanwhile, Ernest Withers captures a still shot of strikers holding signs reading, “I am a man.” And then, mere hours later, news photographer Steve Schapiro records for the historic record a press conference outside the Lorraine Motel after King’s murder. King . was 39 at the time of his violent death. A series of funeral photos by Uzzle, Doris Derby, and Benedict Fernandez follows, picturing Coretta Scott King and two of their young sons. Also pictured are Robert Kennedy and his wife, Ethel. Kennedy was assassinated barely two months later, and to put a perspective on how relatively recent this hateful political slaughter occurred, Ethel, at age 95, is still among us.

About halfway around the Lederer Gallery, the civil rights theme takes a distinct turn, marked by a demarcation from black-and-white to a 1956 color photograph by Gordon Parks of a segregated drinking fountain in Mobile, Alabama, starkly labeled as “Colored Only” and “White Only.” The visual record that follows depicts the discrimination and deprivation that motivated the movement toward equal but not separate treatment – from lunch-counter sit-ins in Portsmouth, Virginia, to the summer of 1965 “Freedom Bus Riders” in Oxford, Ohio. While the historical records of these photos, including uncredited newspaper stills, are important from an artistic perspective, one of the most unforgettable is James Korales’ “Selma to Montgomery March, 1965,” projecting a long line of citizen soldiers for equality moving along a steep ridge cast against a storm-threatening sky.

Across the hall in the Healy Gallery, the exhibit continues with Morton Broffman’s photo of a woman sobbing after reading a newspaper headline: “SEN. KENNEDY SHOT IN HEAD.” Hours after that front-page extra edition was printed, Bobby Kennedy died. Another Broffman photo of NAACP marchers in Washington, D.C., shows a placard proclaiming, “You Can Kill a Man, but You Can’t Kill an Idea.”

A photographic series by Sheila Pree Bright references more recent deadly encounters involving civil rights violations, including a protest in Baltimore over the death of Freddie Gray in city police custody. The final image in this civil rights visual essay offers a peaceful footnote. It’s a color photo of a puppy asleep in a pew at the Rev. King’s former church, Ebenezer Baptist in Birmingham.

***

Aside from “A Fire That No Water Can Put Out,” there’s much more to see in new exhibits at AAM. In a show of sculptural pieces – mostly of marble – “Public/Private” by Sebastian Martorana, you’ll recognize the subject of a cartoonish bust in white marble mounted on cedar wood. In case you don’t get it right away, check the title: I won’t give it away here. In the next gallery, adorable baby boots and mittens along with busts of the “Friendly Ghost” and “Kermit” (the Muppet frog) are at the very least smile-worthy.

Moving on to the hallway gallery upstairs, “Immaculate Landscapes” by Brett Weston (1911-1993) takes you on a black-and-white pictorial travelog. Most images are shot in Alaska and Hawaii and points between and beyond. “Ice and Water, Alaska” captures 1970 ice floes that have melted long ago. Pity the polar bears. “Lava, Hawaii,” from 1982, depicts fascinating textures that make you wonder if they were solid or liquid at the time. Some images are cliches from early in his career, such as 1952’s “Farm Landscape,” with cloud formations competing with the pastures and fields below. More appealing is Weston’s “Building Reflection” series of glass-encased urban highrises photographed with fun-house mirror effects.

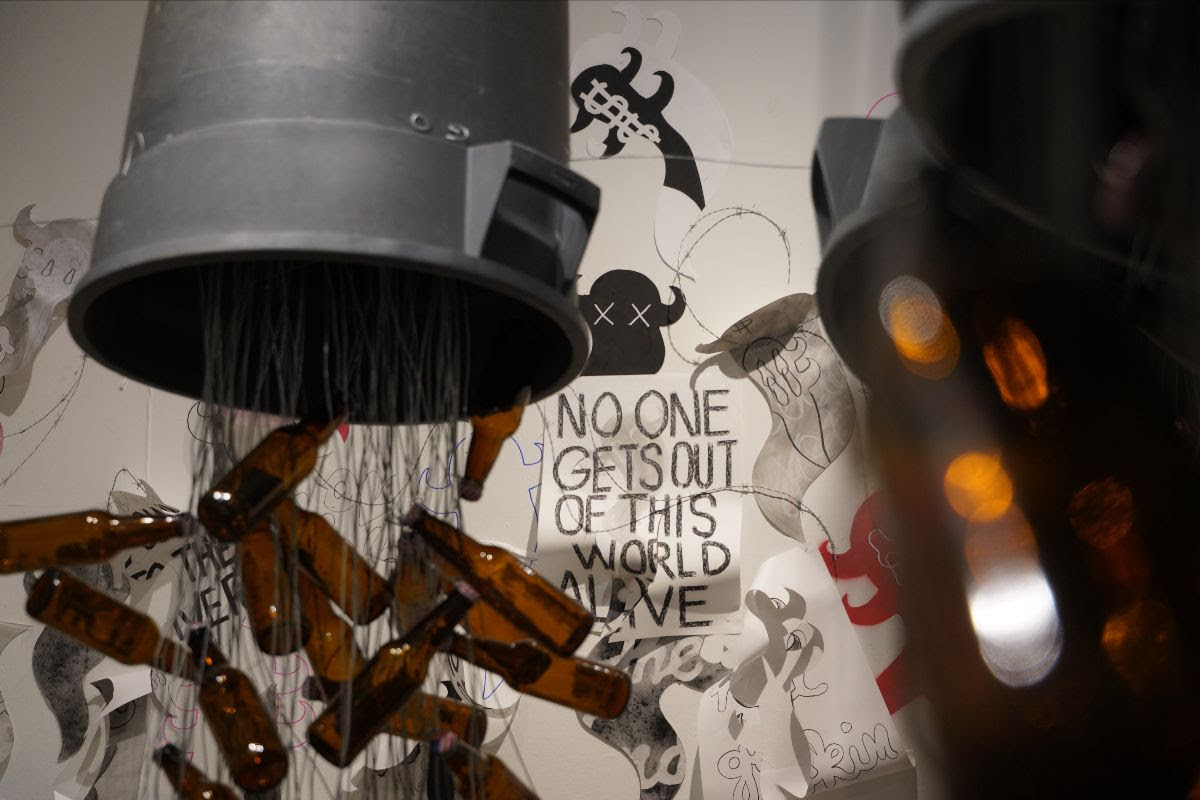

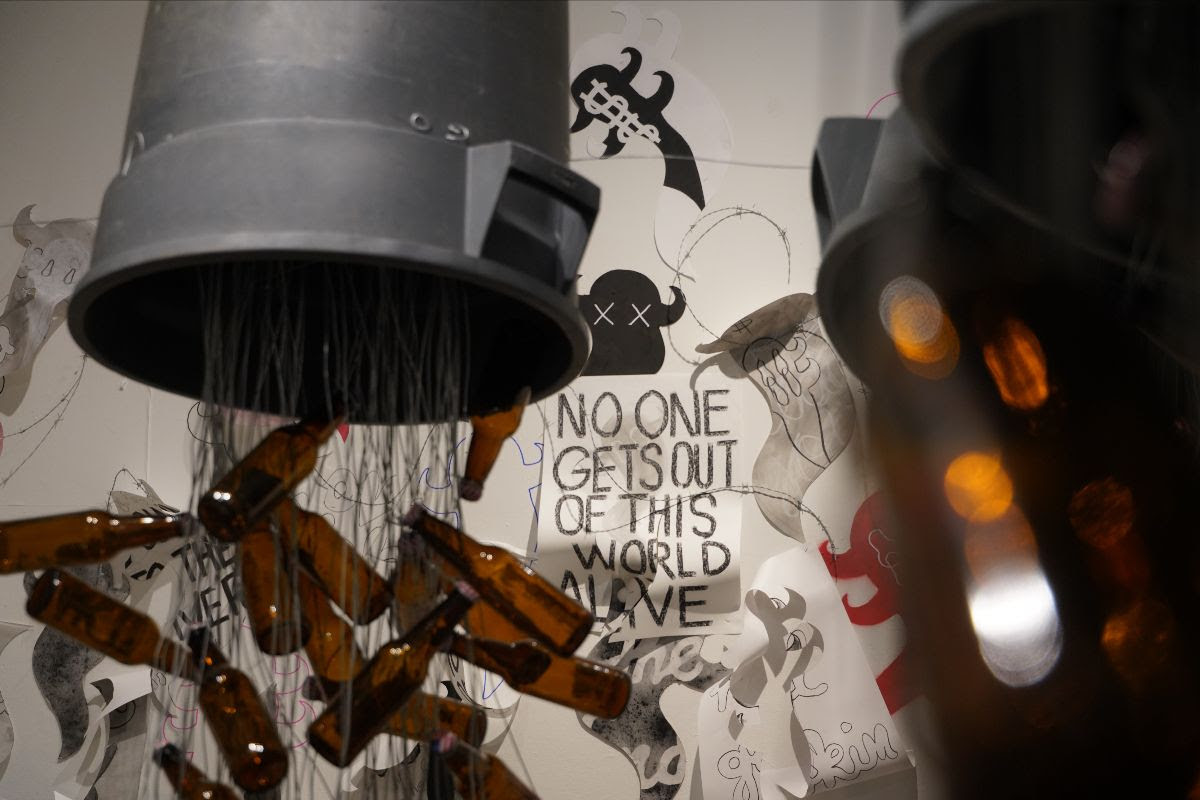

Before you leave, if you haven’t already done so, see what you make of the immersive “Dominion” installation in the museum’s entryway Atrium. Marty Two Bulls Jr. critiques American consumerism and its harmful environmental effects. He focuses on the barely averted extinction of bison herds that defined the livelihood of the nomadic Oglala Lakota tribe of the Northern Plains. As seen from above, paper cutouts of buffaloes are strewn on walls and windows of the Atrium – with bronze-colored beer bottles suspended as they appear to be falling out of overturned trash cans. Some “buffaloes” are branded with dollar signs, while others are marked with interactive QR codes. Take a picture of one or two on your cell phone to see what you may learn.

Marty Two Bulls Jr. will present an artist’s talk at AAM on March 1.

‘A Fire That No Water Could Put Out’

Photographs from the Civil Rights Movement, through March 10 at the Academy Art Museum, 106 South St., Easton. “King: A Filmed Record . . . Montgomery to Memphis” will be screened, free, on February 17. Also exhibited now are “Sebastian Martorana: Public/Private” through March 24, “Brett Weston: Immaculate Landscapes” through March 31, and “Marty Two Bulls Jr.: Dominion” through September 1, 2024. academyartmuseum.org

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.