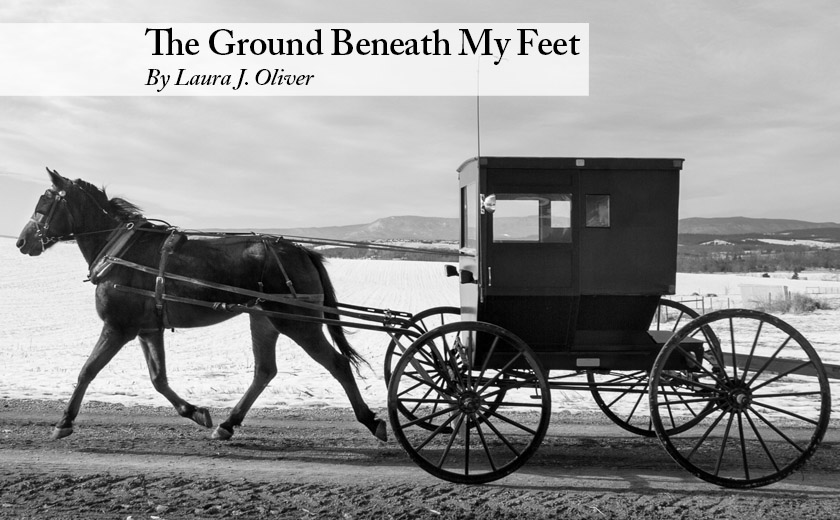

My great-great grandmother, Mary Jane Aten and her husband Robert, set out in their horse and buggy on a cold November afternoon in 1900 to visit their son Henry in the town of Vermont, Illinois. Along the way, they stopped in Table Grove for lunch with their daughter, Flora, staying for a couple of hours of roast turkey and talk. When they resumed their journey, they closed the buggy’s side curtains against the autumn wind, and Robert snugged down the earflaps on his brown cap. Mary Jane leaned against him, bundled up tight in a coat with a hood.

This is why, the theory goes, they never heard the train at the crossing two miles north of Vermont where the CB and Q road crosses the tracks. Robert drove the buggy onto the rails, directly into the path of the train barreling toward them. The conductor saw the carriage, applied the brakes, and frantically blew the whistle, causing the horse to freeze. Barely able to slow, the train plowed into them at near full speed.

In an instant the buggy was kindling, no piece left bigger than the wheels. The bulk of it remained on the train’s pilot. When the crew doubled back, they found the horse was uninjured—though the force of the impact had stripped him of his bridle and harness.

My great-great-grandparents had been married since 1852 and had nine children. But what moves me about this story is where and how they were found. Robert 82 and Mary Jane 72 were discovered lying together on the bank—Robert’s arm flung outward, and Mary Jane cradled in the crook of it—as if they were sleeping. Their catastrophic wounds were invisible—their clothing untorn– and her hair, long and still dark, remained tied back like a girl’s.

Ridiculously, I’m grateful more than 100 years later that an obedient horse was not hurt. And less ridiculously, that two people who were ahead of me in the family line stayed married for more than half a century and loved nine children. I like how that feels because I’ve been seeking a solid sense of self for most of my adult years.

My father left when I was so young that when, at 36, I saw him seated next to my mother at Capers for brunch, I was silently stunned. It was as if I had been swimming off the deep end all my life, and my toes had just touched the bottom. Suddenly I was someone new—someone with parents—not just a mother. For the first time, there was solid ground beneath my feet. I felt like I came from somewhere. And we all need that– our origin story—and I’ve come to realize an origin story starts long before your parents. It begins as far back as you need it to.

You can look for clues in a variety of places, family history, stories like Robert’s and Mary Jane’s, and even your genetic makeup–which is why I was excited when I was gifted with one of the very first DNA test kits to come on the market.

At last, I would discover more clues as to who I am from the inside out. I expected to have Robert and Mary Jane’s English and Scottish ancestry confirmed and hoped for a surprise or two. I sent in my samples, waited a week, and logged onto the internet using a private barcode to see the results of what the company called cutting-edge science. The results of my DNA sample were depicted graphically as a target overlaying the ten countries whose populations most closely match my genetic identity. I stared expectantly at northern Europe, but there was nothing there. Nothing.

“So,” the ever-helpful Mr. Oliver said as we scrutinized the screen. “Your primary countries of origin are… Tanzania…” he pushed back from the computer to assess me quizzically, then turned back to the screen, “and Mozambique.”

“Surprise,” he said, but he said it in Leah-the-dog’s voice—which is how we often communicate around here when we want to deflect emotion or, as in this case, we just want to make the other person laugh.

Not a drop of Scottish or English blood. “That can’t be me!” I snapped, indignant and inexplicably offended. Because I had assumed the accuracy of the results and they didn’t jibe with what I knew to be true, I was caught in a space-time anomaly in which I had no identity at all. I think I felt huffy because I felt tricked.

But in reading the fine print, I realized the company’s claim that its analysis was as personal as a fingerprint was valid because it was also just as worthless in decoding ancestry. Their business was analyzing “Junk” DNA, which is non-coding, and though we are still searching, it seems to have no purpose at all, even though it comprises more than 75% of your entire genome. Technically, however, the company was correct. Since early man walked out of Africa, it’s everyone’s home address. When the major religions of the world claim, “we are one,” and anthropologists refer to the “family of man,” they are not wrong.

Until 1972 Junk DNA was referred to as “Selfish DNA.” It seemed to exist only for itself. Maybe that has been its undoing. Why it now sits in our genome, no longer sending instructions to make us who we are but as a record of where we have been.

Body, mind, spirit—we walked out of Africa with all three intricately linked and evolving only to demonstrate that what exists only for itself loses dominion.

My great-great grandparents’ lives ended bookended by family—a son in Vermont, a daughter in Table Grove. Like them, may we all die knowing who we are, in the arms of someone we love.

Laura J. Oliver is an award-winning developmental book editor and writing coach, who has taught writing at the University of Maryland and St. John’s College. She is the author of The Story Within (Penguin Random House). Co-creator of The Writing Intensive at St. John’s College, she is the recipient of a Maryland State Arts Council Individual Artist Award in Fiction, an Anne Arundel County Arts Council Literary Arts Award winner, a two-time Glimmer Train Short Fiction finalist, and her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her website can be found here.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.