Alexander Calder (1898-1976) was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania into a family of artists.. His grandfather and father were known for their public sculpture commissions, and his mother was a portrait artist. Alexander, better known as Sandy, started making small sculptures of mixed materials by1902. The first one was an elephant. By age ten, Sandy had a small workshop. However, his parents having experienced the artist life, wanted Sandy to choose another line of work. Sandy graduated from the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey with a degree in mechanical engineering. The following inscription was written in his yearbook: “Sandy is evidently always happy, or perhaps up to some joke, for his face is always wrapped up in that same mischievous, juvenile grin. This is certainly the index to the man’s character in this case, for he is one of the best natured fellows there is.”

Calder held several jobs as a hydraulic engineer, draughtsman, mechanic, and timekeeper at a logging camp. From the camp he wrote home to request paint and brushes to paint the mountain scenery. He started his art studies in 1923 at the Art Students League in New York City. He frequently visited Coney Island, the circus, and the Bronx and Central Park zoos. He began the creation of the “Calder Circus” (1926-1931). Over the next several years the “circus” grew to over 70 miniatures of performers, almost 100 accessories, 30 musical instruments, records, and noisemakers. Eventually the work filled five suitcases. The figures were made of wire, wood, metal, cloth, yarn, cardboard, leather, cloth, string, rubber tubing, corks, buttons, rhinestones, pipe cleaners, bottle caps, and other found objects.

Calder moved back and forth from Paris to New York from 1926 until 1933. He performed the show over 70 times. In Paris his audience included critics, collectors, and artists from the theatre, and literature, including the Parisienne avant-garde, Miro, Duchamp, Cocteau, and Leger. Paris audience members sat on bleachers made from champagne crates, and they ate peanuts. They were given noisemakers to sound when Calder gave the signal. In New York his audience included members of high society. Calder announced the acts in French or English, choreographed all the movement, gave voice to the performers and animals, played music, and created sound effects. The shows were so well received they often lasted for two hours.

At the lower right-side corner of the display is the “Little Clown Trumpeter.” In a performance, Calder would place a balloon in the clowns mouth and then blow through the hose until the balloon burst and knocked over the bearded lady that was placed in front of him. The figures in the middle are a cowboy wearing wooly chaps, a bull made of wire and corks, a cowboy on horseback wearing a red bandana and holding his black hat, and a woman waving an American flag. A street lamp, and a dachshund fill in the left front corner. At the rear, three trapeze artists hold onto the high wire that Calder would vibrate to animate them. In case one should fall, a net was suspended beneath.

The clown (10.5’’x7’75’’x5’75’’) is dressed in a long brown coat with arms made of Yarn. Calder would strip off the clown’s clothes in layers until he was dressed in coveralls, and revealed to be a thin wire figure. The camel is a cloth sculpture sewn together and wired for stability (6.5’’x5’75’’x4’25’’). The kangaroo is made from shaped pieces of metal nailed to a wooden base on a wheel. When the kangaroo is pulled by an attached cord its legs appear to move, similar to a child’s pull toy. As a result of the success of his inventions, Calder went to Oshkosh, Wisconsin, in 1927, to meet with a children’s toy manufacturer. They signed a contract for his Action Toys: a hopping kangaroo, a skating bear, and a goldfish that appeared to swim, opening and closing its gills when pulled.

Standing in the center ring, ringmaster Monsieur Loyal in top hat and tails points to the lion in cage. Out of the cage for a performance, the lion completed a few tricks and then sat on a pedestal. The lion then dropped a few chestnuts as if popping, which were quickly removed. Calder planned to add scent to the performance, but he found musk perfume too expensive and abandoned the idea.

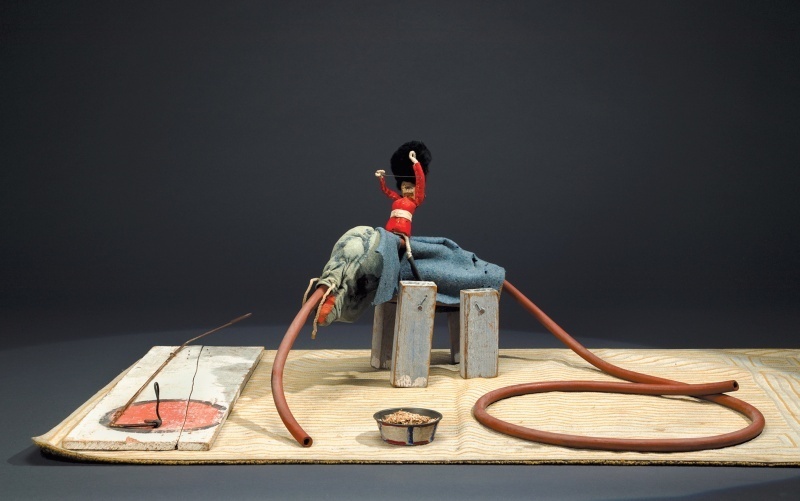

Other attractions at the Calder Circus included a sword swallower, Sultan of Senegambia, who threw spears and axes, a belly dancer who gyrated, a horse and chariot, cows, seals, a tightrope act, dogs, and other acts from the circus and the side show. The rider on the elephant appears to an English Kings Guard wearing a bearskin hat and bright red tunic. The elephant has a tube running through its body. In a performance the tube/trunk hung down as if the elephant were drinking water, but when Calder blew into the tube the trunk raised up and spewed out small pieces of paper to give the effect of spaying water.

Calder included well-known circus performers in his show. May Wirth, a famous bareback rider from the Barnum and Bailey circus, performed in the center ring. “Rigoulot the Strong” was a popular performer. When Calder loosened the cord, Rigoulot bent forward and picked up the barbell with his wire-hook hands. When the cord was tightened, the figure returned to the upright position and groaned. The figure then proceeded to lift the barbell backward and over his head.

During the run of the “Calder Circus” from1926 to 1931, Calder added a new dimension to the show with a series of figures constructed of wire only (1929). After meeting Piet Mondrian in 1930 and after being introduced to totally abstract art, he wrote a letter to Mondrian stating it was “the shock that converted me. It was like the baby being slapped to make its lungs start working.” It was then that Calder began to work as he said, “Just as one can compose colors, or forms, so one can compose motions.” He began creating his “Mobiles” in 1931.

Calder gave the last performance of the Calder Circus in 1961, for the filming of Le Cirque de Calder by Carlos Vilardebo. The Whitney Museum in New York City raise $1.25 million in 1932 to the purchase the Circus. The work continues on display at the Whitney.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.