Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) was one of the most important artists of the German Romanticism movement at the beginning of the 19th Century. He was born in Greifswald on the Baltic Sea. His family were strict Lutherans. He was the sixth of ten children. His mother, two sisters, and a brother died when he was young. His interest in art was developed early, and he began to take drawing lessons at age 16. He met Ludwig Gotthard Kosengarten, a poet and preacher, whose works were metaphysical in nature. Kosengarten stated that the beauty of nature was related to the divine, beyond the perception of human senses. Kosengarten’s writings were a significant influence on Friedrich, and on the music of Franz Schubert among others.

Friedrich studied art at the Academy of Copenhagen, where he was able to visit the Royal Picture Gallery’s collection of 17th Century Dutch landscape paintings. He was taught to paint in the Neo-Classical tradition, in which the object was to copy nature precisely. However, the popular literature of the era, Icelandic legends (Prose Edda) and The Poems of Ossian (1760) (Irish mythology), greatly influenced his developing artistic style. “Cross in the Mountains” (Tetschen Altar) (1808) (45” x43”) is considered Friedrich’s first work to abandon Neo-Classical style for Romantism. The Crucifixion is silhouetted on a mountain top against a dramatic pink and gray cloudy sky. Light coming from five sources penetrates the dark clouds to focus on the mountain top and the Crucifixion. An evergreen forest surrounds the mountain top, typical of Friedrich’s native landscape. Evergreens are symbolic of everlasting life.

Friedrich designed the frame of the altarpiece, which was carved according to his specifications. At the bottom center of the frame, he placed the eye of God within a triangle surrounded by rays of heavenly light. At the left is a sheaf of wheat representing the bread of the Eucharist, and at the right are the grapes representing the wine. Above, five cherubs are placed among the palm branches. A single star is placed in the center. Friedrich intended the altarpiece to be a gift to the King Adolphus IV of Sweden in recognition of his part in resisting Napoleon’s attempts to conquer Sweden. However, Adolphus IV was deposed in 1808. Count von Thun-Hohenstein convinced Friedrich to sell the altarpiece to him for his castle chapel in Tetschen, Bohemia.

Friedrich exhibited the painting/altarpiece at the Academy in Berlin in 1810, where it received mixed reviews. Basilius Von Ramdohr, a conservative lawyer, art critic, and amateur artist, published a long article in Dresden, rejecting Friedrich’s use of landscape as a religious painting, calling it “a veritable presumption, if landscape painting were to sneak into the church and creep onto the altar.” Friedrich responded that his intention indeed was to compare the rays of evening sunlight to the Heavenly Father.

“Monk by the Sea” (1809) (43” x68’’) broke with all of traditional landscapes by eliminating everything but the small figure of a solitary monk within the vast panorama of land, sea, and sky. X-rays show that Friedrich had painted two boats on either side of the monk and a flock of sea birds in the sky, but painted them out. Reactions of viewers varied, but generally unfavorable. Marie von Kugelgen, an early admirer of Friedrich’s work, wrote to a friend about her reaction to the work: “A vast endless expanse of sky…still, no wind, no moon, no storm–indeed a storm would have been some consolation for then one would at least see life and movement somewhere. On the unending sea there is no boat, no ship, not even a sea monster…and in the sand not even a blade of grass.”

The German poet, writer, and journalist Heinrich von Kleist described the painting in 1810: “Nothing could be more somber nor more disquieting than to be placed thus in the world: the one sign of life in the immensity of the kingdom of death, the lonely center of a lonely circle…the picture seems somehow apocalyptic…its monotony and boundlessness are only contained by the frame itself.”

“The Monk by the Sea” and its companion painting “Abbey in Oak Forest,” depicting the burial of a monk in a ruined church yard, were exhibited together. Their purchase by Prussian King Frederick Wilhelm III surprised the critics. Friedrich’s venture into a new style of painting took hold. The isolation and emptiness reflected for some viewers the results of Napoleon’s invasion of Germany. To those viewers, Friedrich’s paintings exhibited a patriotic image of contemporary Germany, diminished but not defeated. Friedrich was elected a member in the Prussian Academy of Art as a result of these paintings.

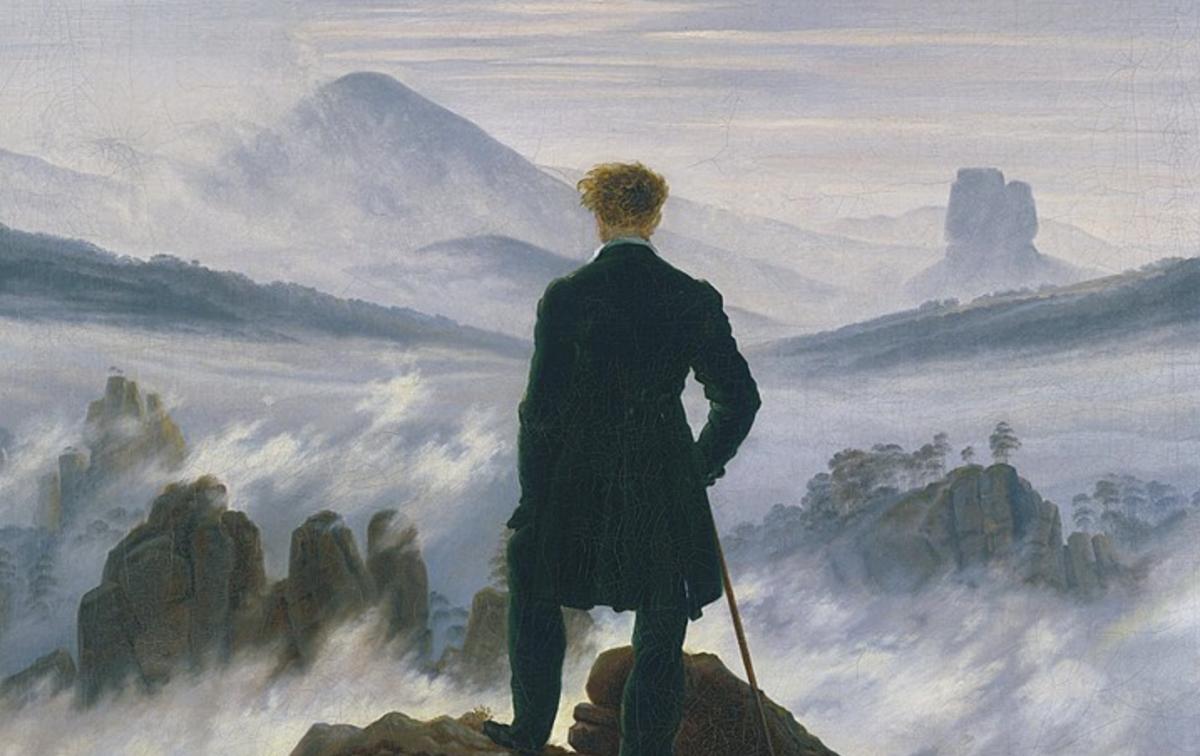

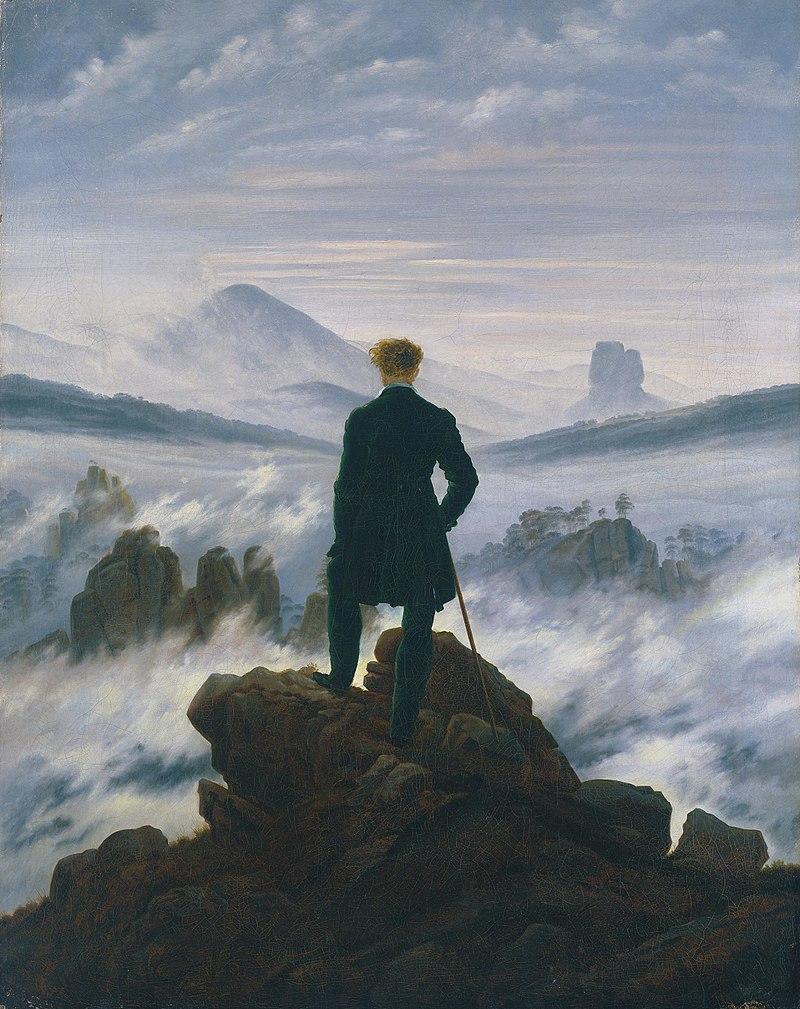

“The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” (1818) (38.5’’ x29”) is considered by art historians to be a masterpiece of the Romantic Movement. The single male figure, dressed in dark green and holding a cane, stands on a rocky outcropping that rises dramatically in the foreground of the painting. Bearing a few green trees, jagged rocks pierce the fog. Two ridges are painted so they come to a point at the chest of the man. Mist-covered mountains and clouds stretch into infinity. Friedrich wrote, “When a region cloaks itself in mist, it appears larger and more sublime, elevating the imagination, and rousing the expectations like a veiled girl.”

Friedrich most often employed the technique “ruckenfigur.” Figures are placed with their backs to the viewer, inviting the viewer to gaze upon the scene from the same perspective, but giving no suggestion of their reaction to the scene. Friedrich stated, “The artist should paint not only what he has in front of him but also what he sees inside himself.” Friedrich sought the spiritual and the divine.

The subject has often thought to be a self-portrait, because the figure with the red hair resembled Friedrich. He dressed the figure in altdeutsche (old German clothing), the clothing of Germany’s heroic age, 16th and 17th Centuries. A Nationalist, Friedrich supported a new more liberal government and wanted to abolish the rule of the German nobility. Nationalists wore the old German clothing as a form of protest. The trend was so threatening to the German nobility that altdeutsche clothing was banned in 1819.

Friedrich married Christiane Caroline Bommer, 19 years his junior, in January 1818. They had three children. The family lived a solitary life. Following his marriage, Friedrich often included a second figure in his paintings. “Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon” (1818-1825) (13” x 17.3’’) depicts two figures on a rugged hill top, their backs to the viewer. Critics generally refer to them as Friedrich and his wife. The man wears altdeutsche clothing, and the woman’s hand rests calmly on his shoulder. The couple stand close together, contemplating the full moon and the distant landscape.

Friedrich places the couple under several evergreen trees, their branches forming a lacy pattern against the moonlit sky. The other major element in the painting, taking up half the hill top, is an ancient tree. Its roots, partially pulled up from the earth, are exposed and form hairy fingers. The wide-spread branches are bare. The tree lists to the right, but remains standing. Throughout the ages, the Moon has always been considered as feminine and a symbol of the cycle of the seasons and of abundance. The full moon completes a heavenly cycle, the time to prepare for the future. Friedrich’s painting communicates hope for the future.

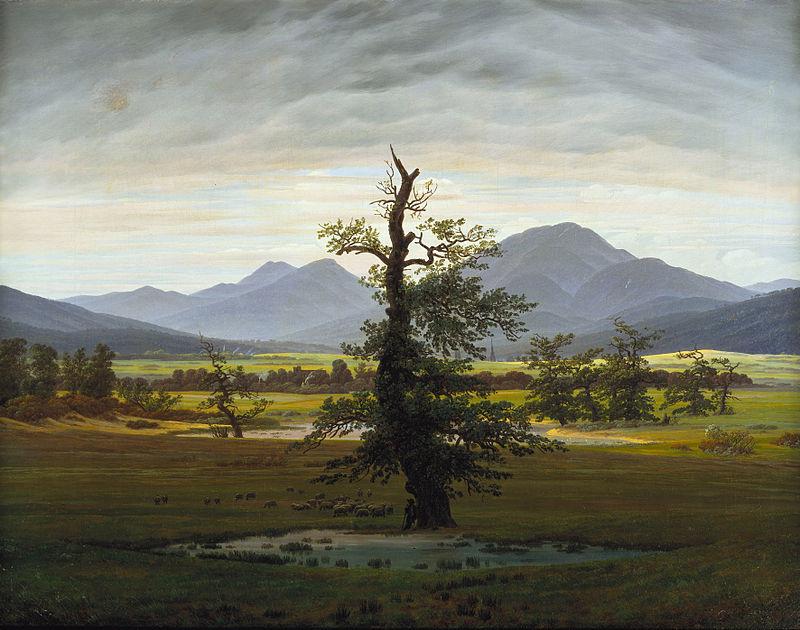

Friedrich’s patrons included the Grand Duke Nikolai Pavlovich of Russia and his wife Alexandra Feodrovna. They visited Friedrich’s studio in 1820 and purchased several paintings to take back to St. Petersburg. Their continued patronage, and that of other Russian nobles, sustained the artist when the Romantic style began to go out of favor in the 1830’s. Friedrich suffered several major episodes of depression during his life, and was said to be the “most solitary of the solitary” by his friends. “Solitary Tree” (1822) (21.6” x28”), was one of two works commissioned by Joachim Wagener, a banker and an art patron. The works were to show a morning and an evening landscape. “Solitary Tree” depicts a beautiful morning as the sun rises over a country village. A large tree at the center of the composition connects the earth and heaven. The size of the trunk indicates the tree has experienced a long life. The lower branches still support green leaves, but the top branches are dead. Friedrich organizes the top branches as a reference to the image of the dead Christ on the cross.

Under the tree, a shepherd leans on his staff and against the tree trunk. His flock of sheep graze quietly in the pasture. Like the dead branches of the tree, the artists inclusion of the shepherd and his sheep refer to the religious connections that Friedrich found in nature. The panoramic landscape beyond the tree contains a stream and stands of evergreens. A small village is nestled to the left of the tree. Bright sunlit pastures and a mountain range spread out under an early morning sky. Hardly visible, a gray church spire stands to the right of the tree at the base of the mountains. The sun has risen over the distant landscape, but sunlight has yet fully to reach the solitary tree. The tree has weathered a long life and endures.

Friedrich’s popularity declined during the last 15 years of his life as the Romantic style he helped to create was considered old fashioned. Throughout his life, he suffered from recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD). He had a stroke in1835 that left him partially paralyzed. He continued to paint, although his painting were smaller and often watercolors rather than oil. He died in 1840. An exhibition in Berlin in 1906 brought his work to the attention of expressionist painters including Bocklin, Kirchner, and Kandinsky, and to the American painters of the Hudson River School. When Hitler discovered Friedrich’s beautiful German landscape paintings, he declared Friedrich to be a forefather of Nazism. This unfortunate and inaccurate association caused a decline of interest in Friedrich. However, Friedrich’s reputation was restored in the 1950’s by the Surrealists, Abstract Expressionists, and a large number of international artists. Friedrich is now considered a painter of international importance.

“I am not so weak as to submit to the demands of the age when they go against my convictions. I spin a cocoon around myself; let others do the same. I shall leave it to time to show what will come of it: a brilliant butterfly or maggot.” (Caspar David Friedrich)

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Sonia Jallane says

Would you be able to tell me if CFD had any connection with Schubert – Did the painting inspire the piano Wanderer fantasia?