“Today, all I know is that I have learned to interpret the whole of life in terms of conspiracy,” George Smiley, in a letter to his wife at the conclusion of John le Carré’s novel The Honorable Schoolboy (1977).

The author who epitomized the literary spy genre kept one last novel concealed from his vast readership before he passed in December 2020. Silverview is a relatively short tale set primarily in Britain where John le Carré’s descriptions of his native land masterfully capture the remnants of the Cold War and a world that has moved on. The dust jacket illustration alludes to a passage with characters walking through the remains of a civilization on a run-down quayside with “distant forests of abandoned aerials rising out of the mist, abandoned hangars, barracks, accommodation blocks and control rooms, pagodas on elephantine legs for stress-testing atom bombs, with curved roofs but no walls in case the worst happens.” England’s more pastoral landscapes and small towns, as well as London, are depicted in cinematic detail and read like a deeply affectionate adieu from the aging author.

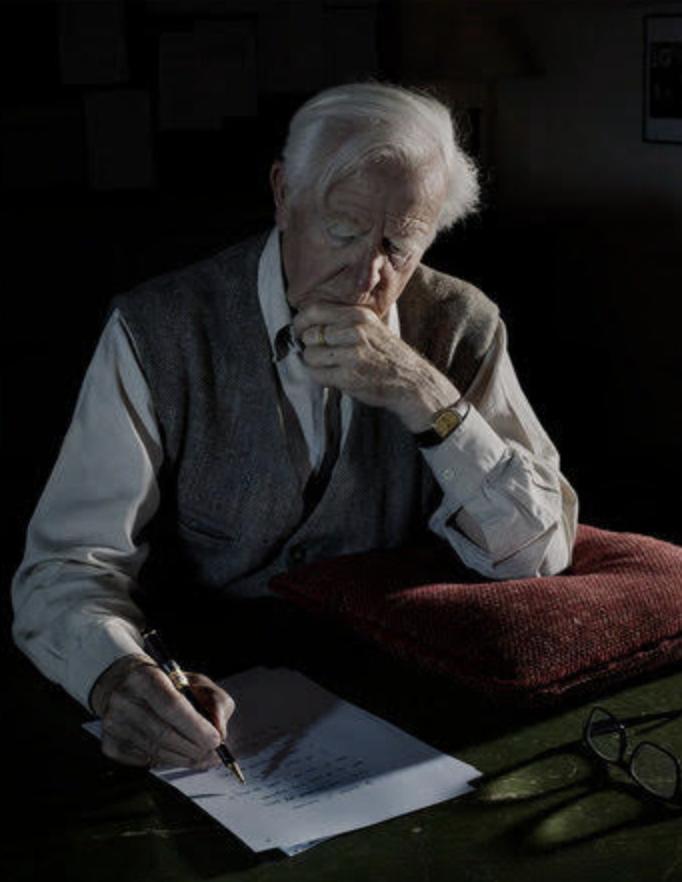

Yet as Le Carré readers would expect, this posthumously published (October 2021) novel includes many remembered scenes of recent history in distant lands and several vividly imagined foreign characters. With his half-French pseudonym, the author (whose real name is David Cornwell) was a cosmopolitan who spoke German with native fluency—the novel title itself is a translation of a name, Silberblick, the house in Weimar where Nietzsche spent his final days.

Yet as Le Carré readers would expect, this posthumously published (October 2021) novel includes many remembered scenes of recent history in distant lands and several vividly imagined foreign characters. With his half-French pseudonym, the author (whose real name is David Cornwell) was a cosmopolitan who spoke German with native fluency—the novel title itself is a translation of a name, Silberblick, the house in Weimar where Nietzsche spent his final days.

Le Carré returns in his twenty-sixth novel to the subject of an internal security investigation, this time a cyber breach. Gone is the impassive yet deeply perceptive George Smiley, the author’s celebrated mole-hunting, agent-running character seen in eleven prior novels. Enter Stewart Proctor, the nearly retired head of internal security for the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS or MI6, previously euphemized by the author as “the Circus,” more recently “the service” or “the office”). Proctor, like Smiley, suffers from marital problems and inferior superiors. Unlike his predecessor who largely ignored his wife’s promiscuity, Proctor uses his bloodhound sense to sniff out his wife’s suspected infidelity to his satisfaction through a probing phone conversation that borders on an interrogation. Proctor hangs up on her, which is something Smiley would never do to his wife.

Le Carré is particularly skillful when exploiting the advantageous gap afforded to novelists between speech and thought during these interrogatory dialogues. At one point Proctor listens to his wife’s travel schedule and thinks to himself: Too much information. One lie after another in case the last one didn’t work. Le Carré uses this gap in several other ways—such as having a younger character, bookstore owner Julian Lawndsley, first take in what is said then pose questions to himself about what is really meant by the star of the book, the aging polyglot Edward Avon.

A complex personage of Polish origins and many lives, Avon speaks his native tongue, French and German like the author, as well as Czech, Serbo-Croatian and “a bit of Hungarian.” Also known as Edvard, Ted, Teddy and Florian, he exudes a charming false modesty through his excessively eloquent English. Avon’s obvious intelligence is undermined by his romantic attachment to a succession of causes, which is how he ends up in hot water.

A dual storyline is established around Proctor’s investigation and Lawndsley’s transition from City trader to the owner of an East Anglia bookshop where Avon becomes a frequent visitor. Through the voice of the Avon character, the reader experiences the full effects of Le Carré’s worldliness and the hall-of-mirrors quality of an agent’s life. Elsewhere the author says of his style and technique that he combines “classic austerity” with “neurotic excess” and often disguises the one with the other, which might well describe the voice given to Avon.

The novel is populated by numerous strong women characters who are essential to the tale, almost as if the author went all out to disarm his critics. Readers of Adam Sisman’s John le Carré: The Biography (2015) will be aware that the novelist suffered abandonment by his mother as a child and that critics of prior novels have found shortcomings with his female characters. Readers of the novel might want to know more about Avon’s intriguingly elusive lovers—the Jordanian militant Salma and the Polish dancer Ania. Readers will not, however, be disappointed by the authenticity of Lily, a foul- mouthed, single mother of a mixed-race child; or by Lily’s retiring intelligence analyst mother, Deborah, who seems to harbor racist sentiments for her grandchild yet gets along fine with her black, Bahamian caregiver.

Then there is Joan, the retired agent-handler whom Le Carré portrays with great love despite the failings of age and to whom the author gives stunning descriptive powers of remembered scenes of war in the hills outside Sarajevo. Joan and her husband Philip, who is recovering from a stroke, give voice to some of the most perceptive character analyses regarding agents—these views are so insightful and forcefully expressed that they can be read as lessons on ignoring the elderly and injured at one’s peril. More sagacity comes through in depictions of the stages of retirement with Stewart Proctor on the verge, Deborah Avon in the process, and Joan and Philip recently retired. Proctor drops what is perhaps the ultimate pearl of wisdom in the novel when he wonders to himself whether marriage is just “one big cover story.”

Silverview is not a work on the scale of Our Game (1995) or Absolute Friends (2003), to mention two colossal Le Carré novels that that have not yet made it to the silver screen.

A younger version of the author might have written more than the 208 large-type pages in this Viking hardback—although the concision in this last work may come as a relief to readers who have struggled with the outsized casts of characters, often with aliases, and plots that can be tortiously complex making for what reviewers sometimes said were books that are too long. The 1979 seven-part BBC television series based on the novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, for example, was generally well received yet famously left the public perplexed as to what was going on.

Unfortunately Le Carré is no longer here to give us another of his expertly shifting narratives, which in Silverview is primarily omniscient yet occasionally moves subtly into the first person for the last paragraphs of a chapter. Readers are left wondering about the fate of Edward Avon’s lofty proposal for Lawndsley’s bookstore, the creation of a Republic of Literature. Another well-mannered, multilingual Pole transplanted to England, Joseph Conrad, may have inspired the Avon character. Le Carré has mentioned Conrad as a major literary influence so it’s no stretch to view the Avon character, his Homburg hat in hand among the bookshelves, as an homage to the author of The Secret Agent (1907). The Graham Greene novel Confidential Agent (1939) also comes to mind with regard to Avon as its chief protagonist was a former university professor from Europe on a clandestine mission in Britain and Greene was another acknowledged influence on Le Carré.

Both authors worked for MI6, for a few years at separate times. They famously clashed over what motivated high- ranking British intelligence officer Kim Philby to spy for the Soviet Union. Greene sympathetically cited ideological motives in his introduction to Philby’s memoir. Le Carré characterized the defector as “a shit” and refused to meet him during a trip to Moscow.

In his afterword to Silverview, the author’s youngest son, Nick Cornwell, recounts the circumstances in which the book was written and his own role in making limited edits prior to publication, which he equates to a “clandestine brush pass,” assuring the reader that the novel “is by any reasonable measure pure Le Carré.” Nick shares numerous insights that are worth the price of the book, notably about his father’s relationship with the service and the strong views on it in Silverview—Proctor, for example, concludes that the service has “become too big for its britches.”

There is one passage in the novel which makes one wonder whether Nick might not pick up the story of his father’s life where Sisman’s biography left off—Julian Lawndsley says of his departed father’s archive: “Nothing was too humble to be stored away for his future, non-existent biographers: no sermon note, no unpaid bill or letter—be it from a discarded mistress, an outraged husband, tradesman or bishop— escaped his egomaniacal net.” Will more be published about Le Carré’s life, beyond his semi-autobiographical novel A Perfect Spy (1986) and essay collection The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories from My Life (2016), either by the father or the son? Or could this passage indicate authentic humility and be a sign that whatever remains will be left untold?

Published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, in October 2021; 215 pages; price, $28)

Len Bracken is a former international trade reporter for a major news service and the author of numerous books, including three novels.