Ruth Asawa was born in 1926 in Norwalk, California, and she died in San Francisco in 2013. Her parents were immigrants from Japan. They worked on a truck farm picking seasonal crops until 1942, when the family was placed in Japanese internment camps. Her father was interned in a separate camp. The family did not see him for six years.

Asawa became interested in art in elementary school, and her third-grade teacher encouraged her. She won first prize in the school competition. She and her six siblings attended elementary school and Japanese school on Saturdays, where she learned calligraphy using brush and ink. At the internment camp, located at the Santa Anita Racetrack, Asawa studied drawing with three Walt Disney Studio artists, also Japanese.

Asawa and her family later were transferred to the Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas, where she finished high school in 1943. She was awarded a Quaker scholarship to attend Milwaukee State Teachers College. She completed the course work; however, she was not allowed to student teach and Wisconsin withheld her teaching certificate because she was Japanese. The College finally awarded in 1998 the degree she had earned all those years ago.

Asawa attended Black Mountain College in Asheville, North Carolina, from 1945 until 1949. Among her instructors were Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Jacob Lawrence, Willem de Kooning, Buckminster Fuller, and Joseph and Anni Albers, all major influencers on the direction of American arts, dance, music, painting, and sculpture after the War.

Ruth Asawa Commemorative United States Postage Stamp (2020)

Ruth Asawa created wire sculptures beginning in the 1950’s. The Ruth Asawa Commemorative United States Postage Stamp (2020) is a depiction of a relatively narrow range of her looped wire sculptures. She did not name her pieces, only numbered them. Information about the dates and measurements is not readily available. This forever postage stamp provides ten examples of Asawa’s looped wire sculptures. The hanging pieces range in length from three feet to twelve feet.

In the summer of 1947, while on a trip to visit Joseph Albers during his sabbatical in Toluca, Mexico, Asawa was inspired by a crocheting technique used to make baskets with galvanized wire: “I was interested in it because of the economy of a line, making something in space, enclosing it without blocking it out. It’s still transparent. I realized that if I was going to make these forms, which interlock and interweave, it can only be done with a line because a line can go anywhere.” The sculptures are looped wire constructions and are numbered, not titled. At her first exhibition at the Peridot Gallery in New York City, Asawa described her sculptures as a “woven mesh not unlike medieval mail. A continuous piece of wire, forms envelop inner forms, yet all forms are visible (transparent). The shadow will reveal an exact shape.” Asawa’s childhood drawings were lines that repeated forms and were evocative of flowers and plants.

“Untitled” (Ruth Asawa on bed kneeling inside looped wire sculpture) (1957)

“Untitled” (Ruth Asawa on bed kneeling inside looped wire sculpture) (1957) (7.75”x7.5’’) is a gelatine silver print photograph by Imogene Cunningham, one of America’s best-known women photographers. Cunningham and Asawa met in 1950, and they became fast friends despite their 43-year age difference. Cunningham’s photographs add to the public’s understanding of Asawa’s process. She experimented with several types of wire, including the more common copper and brass, but also bailing wire. The looped wire sculptures were very large, very intricate, and required a major effort to construct.

Asawa married architect Albert Lanier in 1949, and they had six children. Her internment had taught her to persevere despite obstacles, as did the prejudice against the Japanese people when she was denied the degree she had earned. At Black Mountain College she had experienced equality of treatment on the campus, but not in the town. The newly married couple moved to San Francisco’s Noe Valley because interracial marriage was illegal in all states but California and Washington. Asawa triumphed. She was the subject of a feature article in Life Magazine in 1954. Her work had become a commercial success early in the 1960’s.

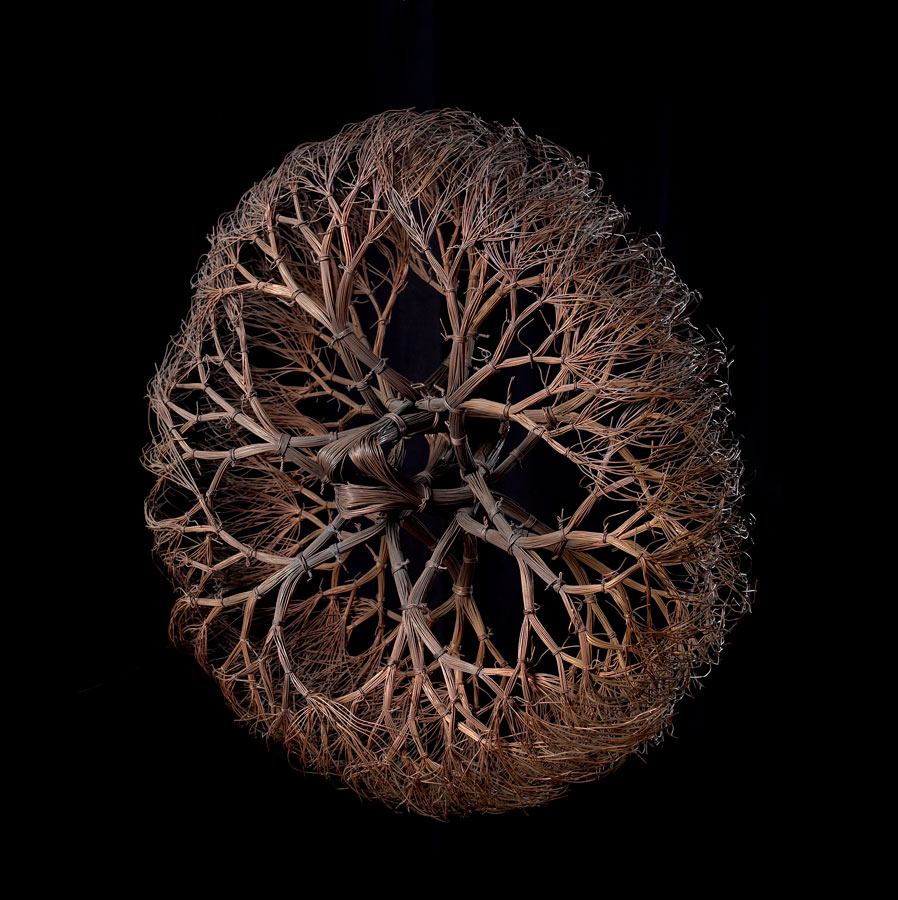

“Desert Flower” (1962)

Asawa became interested in a new technique called tied wire sculpture in 1962, when a friend brought her a desert plant from Death Valley. She tried to draw it: “It was such a tangle that I had to construct it in wire in order to draw it…I began to see all the possibilities, opening up the center and then making it flat on the wall, and putting it on a stand.” She experimented with new branching forms and with some of the Mexican wire crocheting forms. “Desert Flower” (1962) is geometric with a core at the center, similar to the Mexican star and sun patterns. Asawa bundled multiple pieces of wire and tied them before shaping them into the branch forms.

“Tied Wire Sculpture” (1960’s)

Asawa then became interested in cleaning the wire. She was turned down by several industrial plating companies because they considered her work to be insignificant and feminine. She recalled that C&M Plating “took pity on me and were willing to try new things.” After much experimenting, the company was able to electroplate the wire so that it would not rust or otherwise deteriorate. At the center of “Tied Wire Sculpture” (1960’s) is a star pattern. Asawa made the tied wire pieces to be hung on the wall. The diameters of the pieces vary from 36 inches to 60 inches or more, and the pieces extend several inches from the wall.

“Andrea” (1966-68)

Asawa extended her work in metal by experimenting with cast sculpture: “I am fascinated by the possibilities of transforming cold metal into shapes that emulate living organic forms.” She received her first public commission from the City of San Francisco to create a fountain sculpture in Ghirardelli Square. “Andrea” (1966-68) (cast bronze) is a depiction of two mermaids, sea turtles and frogs. One of the mermaids nurses a merbaby. Controversy arose; the work was too feminist for public art. The architect who designed Ghirardelli Square called it a lawn ornament and demanded it be removed. Asawa responded to the criticism: “For the old, it would bring back the fantasy of their childhood, and for the young, it would give them something to remember when they grow old.” The women of San Francisco supported Asawa’s fountain, and it remains in Ghirardelli Square today.

“San Francisco Fountain” (1970-73)

“San Francisco Fountain” (1970-73) (cast bronze) was commissioned for the front of the Grand Hyatt Hotel on Union Square. Asawa recruited over 200 school children, friends, family members, and visitors to mold their images of San Francisco in simple baker’s clay. The molds were cast in bronze, and Asawa assembled them to create the fountain. The Apple Corporation built a new store nearby and wanted the fountain removed. Public outcry prevented its destruction. The fountain was shifted a few feet to accommodate the new building.

“Origami Fountains” (1976)

The two “Origami Fountains” (1976) were placed in Buchanan Mall in San Francisco’s Japantown, their design based on the ancient Japanese paper folding art origami. San Franciscans called Asawa the fountain lady. She also designed “Aurora Fountain” (1986) along the Embarcadero waterfront, and the “Japanese-American Internment Memorial Sculpture” in San Jose (1994).

Not only was Asawa the San Francisco fountain lady, she was a San Francisco artist through and through. Appointed in 1968 to the San Francisco Art Commission, she lobbied for the support of art programs for young children. She was co-founder of Alvarado Workshop for school children. By 1970, Alverado had become a prototype for projects funded by the U.S. Comprehensive Employment and Training Act to employ artists to create public works of art for cities. In 1972 Asawa became a board member of the California Arts Council and the National Endowment for the Arts. She served on Jimmy Carter’s Mental Health Commission in 1977. Governor Jerry Brown appointed her to the California Arts Council during this period.

In 1982 she was one of the founders of the San Francisco School of the Arts, a public high school that later was renamed the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arta. The day of February 12, 1982, was declared Ruth Asawa Day to acknowledge her many contributions to the City as both an artist and a teacher. From 1989 until 1997 she was a trustee of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

“Garden of Remembrance” (2002)

Asawa’s last public commission was the “Garden of Remembrance” (2002) at San Francisco State University. Nineteen Japanese San Francisco State students were removed from their classes by the United States military and taken to internment camps along with 120,000 others. There are 10 boulders placed on the lawn, each from one of the ten internment camps.

“Garden of Remembrance” (waterfall)

The waterfall represents energy and forward movement. Ruth Asawa said, “It was in 1946 when I thought I was modern. But now it’s 2002 and you can’t be modern forever.” She was a teacher, a sculptor, a painter, a printmaker, and did not stop working until she died in 2013. Since then, her work has been recognized in countless exhibitions. The United States Postal Service honored her with ten stamps. Images of them are included at the beginning of this article.

“A child can learn something about color, about design, and about observing objects in nature. If you do that, you grow into a greater awareness of things around you. Art will make people better, more highly skilled in thinking and improving whatever business one goes into, or whatever occupation. It makes a person broader.” (Ruth Asawa)

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.