The boat ride on the Alabama River to the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park in Montgomery takes only fifteen minutes; the morning my friends and I went the ride was cool and serene. It seemed almost too serene given that we were going to a 17-acre site which has as its mission to honor the ten million who were enslaved in the United States, some of whom were transported on the Alabama River to auctions, to imprisonment, separating them from their families, in most cases, forever.

The Sculpture Park is the newest of three Legacy Sites created by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). (https://legacysites.eji.org/) The park opened in March; however, this Juneteenth included a special celebration and dedication of the park and the monument. EJI’s founding director, Bryan Stevenson, has always been committed to what he calls “visual truth-telling” and that the arts have the power to evoke strong and lasting emotions while speaking hard truths. Ancestors’ and artists’ souls are palpably present in the Sculpture Park.

The Sculpture Park is the newest of three Legacy Sites created by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). (https://legacysites.eji.org/) The park opened in March; however, this Juneteenth included a special celebration and dedication of the park and the monument. EJI’s founding director, Bryan Stevenson, has always been committed to what he calls “visual truth-telling” and that the arts have the power to evoke strong and lasting emotions while speaking hard truths. Ancestors’ and artists’ souls are palpably present in the Sculpture Park.

At the entrance to the park, staff told us that photographs could be taken at only two places in the park—the first, at the entrance, with the 16-foot tall bronze bust of a Black woman, “Brick House,” by artist Simone Leigh, and, the second, at the Freedom Monument, at the end of the park. There are forty-eight sculptures by twenty-seven artists in the park, along with various historical artifacts. As I began to walk, I reached for my phone several times to take photos, then remembered the rule. That rule created a calm, quiet, almost reverential atmosphere. No frenetic picture-taking here.

An early section of the park gives an account of The Middle Passage, with an engraved, large wooden map showing the cities on the west coast of Africa where kidnapped Africans were held and loaded on to ships. On each side of the walkway, are four-sided, wooden posts, of varying heights, none more than three feet tall, with the names of cities and counties where these enslaved persons were sold in the United States. Several posts have names of Maryland counties.

Further along the pathway stand ten feet by four foot wooden-like panels, each with the heading, “LAST SEEN.” The Freedom Monument Sculpture Park book states: “Following Emancipation, thousands of formerly enslaved people spent their entire savings to place ads seeking loved ones who had been taken from them.” On these panels are ads, quoted verbatim. On the first panel, at the top, is this ad:

“Information wanted of my mother, Deborah Brown, of Chestertown, Kent Co., Md

“Information wanted of my mother, Deborah Brown, of Chestertown, Kent Co., Md

She was a slave of Daniel Collins, but escaped from him in 1854. Five years ago I heard she was in Canada. Any information of her whereabouts will be thankfully received. Address SARAH ELIZABETH BROOKS [sic], Chester, Pa. June 12, 1869.”

I read this ad several times. I also thought about how those same words, “LAST SEEN,” tragically applied to kidnapped Black persons on the west coast of Africa—those who saw their dear ones for the last time as they were loaded on to slave ships.

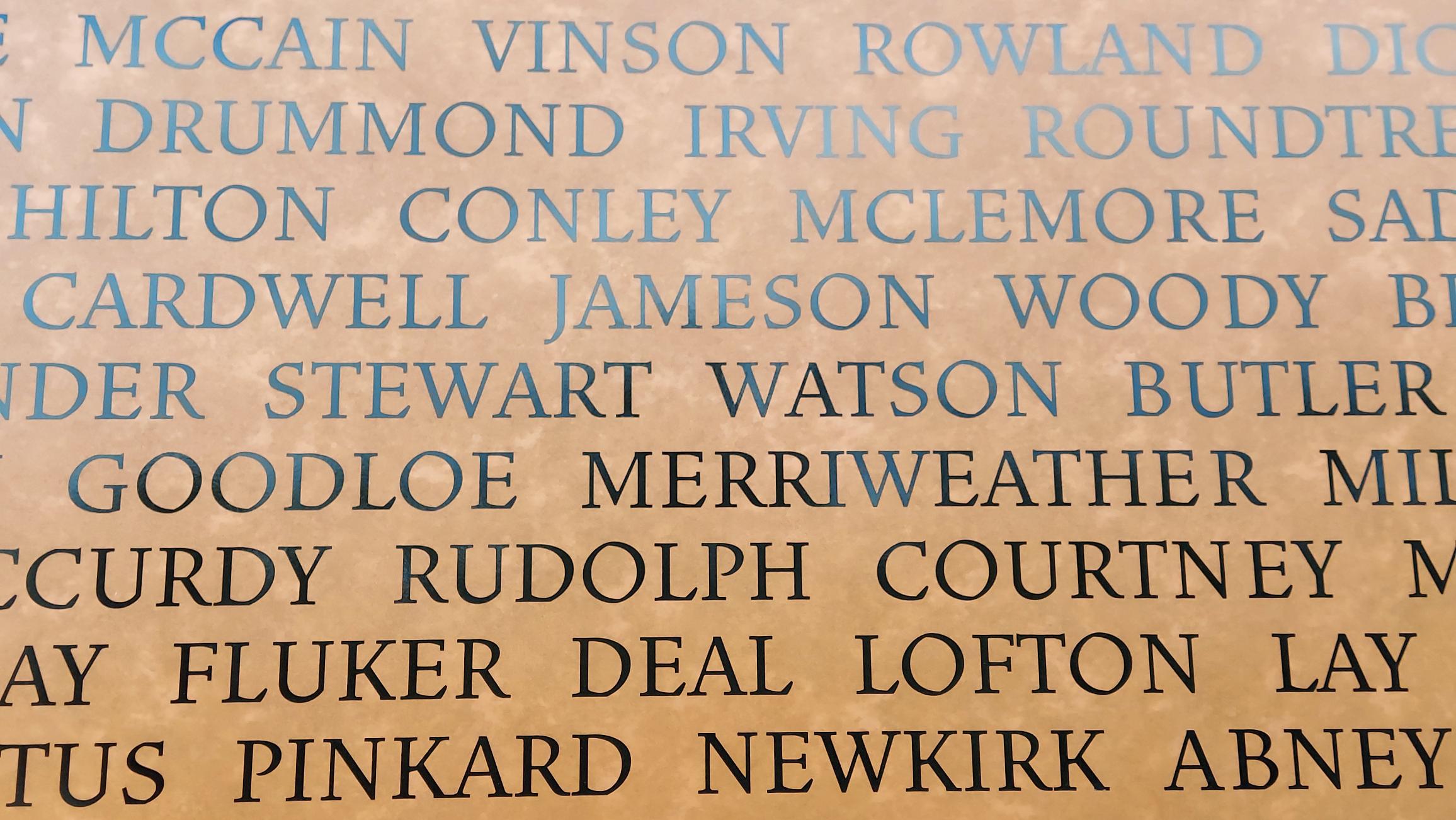

The unexpected reference to Chestertown brought me up short, but there was another reason this visit was personal. Recently I learned that a great-great-great grandfather of mine owned five slaves according to the 1810 census, and, after he had died, his widow and her new husband placed an ad in an1841 Louisville, Kentucky newspaper, stating that five slaves from my great-great-great grandfather’s estate were being sold—two teenaged boys, a twenty-five-year old woman “with a child,” and “a woman about 60 years of age.” Growing up I had no idea about this family history. At the end of the park, I looked up at the National Monument to Freedom, which stands forty-three feet tall and over 150 feet long and has more than 120,000 inscribed surnames that were recorded in the 1870 census by newly freed Black people. I wondered if my slaveholder ancestor’s surname, “Stewart,” was there. Using an app provided by park staff, I found the surname. In 1870, when the census was taken, the twenty-five-year-old woman for sale in Louisville in 1841, would have been around fifty-four, perhaps married. Her child in their late twenties. The teenaged boys in their forties. Maybe they had “Stewart” as a surname, but perhaps they could not wait to leave that surname behind once freed and chose a new one.

On the National Monument to Freedom are these words:

Kidnapped, Trafficked, Enslaved, and Abused

Enduring the horrors and pain of slavery,

You still found the capacity to love,

to dream, to nurture new life, and to triumph.

We honor your strength.

We honor your perseverance in the midst of sorrow.

We honor your struggle for freedom.

Your children love you.

The country you built must honor you.

We acknowledge the tragedy of your enslavement.

We commit to advancing freedom in your name.

And I thought, let it be so.

Gren Whitman says

Thanks for this report! Helps to put July 4 celebrations in righteous perspective.

Patty terry says

This article moved me to tears. Have not found the time to the Freedom Monument park yet, but definitely plan to

CATHY J MORGAN says

Thank you, Kathy. Your description of the week in Montgomery and the Sculpture Park honors such an honorable, educational, emotional event and aim towards reckoning and reconciliation.