“Along the Shore” All photos by Jeff McGuiness

How do you thank a place, not just for showing you things you hadn’t seen before but for showing you a new way of seeing? Maryland’s Eastern Shore did just that for me during the first year of COVID-19—an offering that hasn’t stopped since.

When the virus hit in March of 2020, a dear friend offered my wife and me her guest house in Claiborne beside a pond and large meadow that skirts an inlet of the Chesapeake. The whole of it—the pond, the meadow, the inlet, the roads radiating out from that corner of Talbot County—became an open-air schoolhouse, instructing me in multiple mysteries and cleansing my eyes.

I had planned to take a slow walk later that month from my house near the U.S. Capitol to New York City. Instead, as we all sought distance from each other and the virus, I had this refuge, this silent teacher.

When I did set out, exactly a year later, on a walk that then became a book, I was a changed being, enriched and sensitized by my time in those soggy woods and fields. Neither the walk nor the book would have been what they were without the enchantments, and lessons, of the Eastern Shore.

Leeds Creek

As a Colorado native and longtime Washingtonian, what did I know of pond frogs, redwing blackbirds, the habits of crickets, or the nest-building drama of the osprey every spring? I became attuned, as are all country people, to the phases of the moon and how they color—or make treacherous—any nocturnal stroll.

When I found dead deer in the woods, often led there by the circling vulture, I learned how the tender, juicier parts go first, which birds get first dibs—eagle, vulture, crow—and how long it takes to strip the bones clean. I marveled at the mechanical clicking of geese wings when vast flocks flew overhead.

I learned where the deer slept at night and how the snakes, shrew and foxes moved through the grasses. The budding, blossoming and leafing of the many trees revealed the intricate phases of each spring that I hadn’t understood before.

Snow Geese

The deeper lessons, though, were the human ones. My wanderings spoke to how quickly the land consumes what we leave behind and how the earth, too, wants to forget. How weather and vines will devour the untended barn. How whole family graveyards, if neglected, can be gobbled by earth and woods so that even the headstones sink into the ground.

What we call our history, our telling of the past, is equally slippery. I became obsessed with the memoirs of Frederick Douglass, Talbot County’s greatest native son, and particularly the accounts of his 16th year when he was sent to work for a brutal farmer about a mile from where I slept. He fought with that enslaver—a now-famous moment in the annals of American slavery.

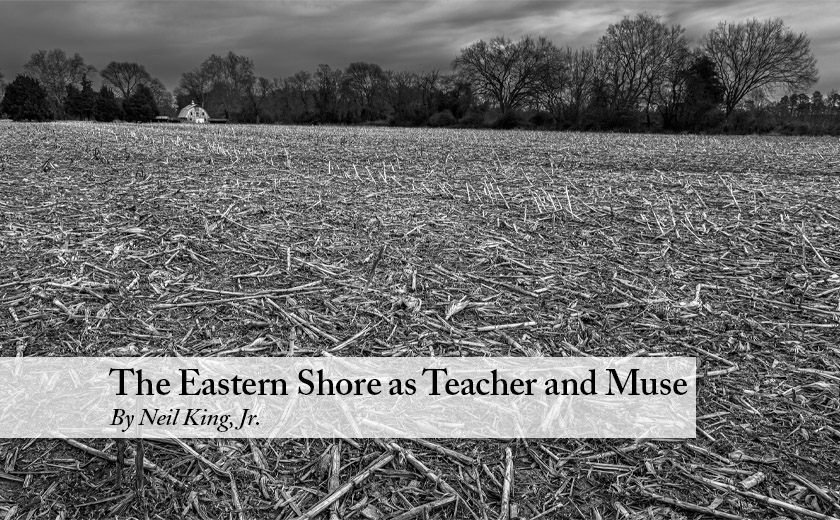

Field in Winter

But where was this field exactly? What had happened to the house? Did anyone along that stretch of highway between St. Michael and Tilghman Island have any knowledge of these events? When I finally pinpointed the place, there was no marker, no remembrance of any kind. Just a soggy cornfield with cars speeding by.

That quest drove home the vital importance of place and of honoring the land for the stories it holds, even when they remain mute. The micro-observing of one patch of Talbot County trained me in a more devotional way of interacting with the land—a slower, more deliberate, more attentive way of seeing.

All this fed into my long walk in the spring of 2021. That journey didn’t bring me anywhere near the Eastern Shore but instead took me straight north from Washington into Pennsylvania and then east to Philadelphia and on to New York City.

But with every step, I carried a bit of the Shore with me, a deepened awareness and attentiveness that those many months had given. I better understood the stories of all I passed along the way. The railbeds, the intricate stone walls, the canals dug with unimaginable exertion, the varied styles of the old barns, all whispered secrets I might not have heard otherwise. For which I give the place abundant thanks.

Neil King Jr. is a Washington-based writer and the author of “American Ramble: A Walk of Memory and Renewal.”

Jeff McGuiness was the senior partner of a public policy law firm based in Washington, DC, and founder of HR Policy Association. A fine arts major in college who served as a photographer in the Air Force during the Vietnam War Era, he has picked up where he left off 50 years ago with Bay Photographic Works. He lives in St. Michaels, MD.

The Bookplate is continuing its 2024 season of author lectures on Thursday, April 4th, with Neil King, Jr. for a 6 pm event at The Kitchen and Pub at The Imperial Hotel in Chestertown.

Paula Wilhelm says

Thank you for your observations and perspective.

Matthew W. Tobriner says

Neil, Your beautiful sililoquy about absorbing nature and its connections to human history is quite inspiring. By chance, due to my fiendship with Lucy Maddox and a discussion we had as to what animal we would choose to be if given the chance, she loaned me a book enitled “Ring of Bright Water” by Gavin Maxwell (Longmans,Green and Co., London 1960). I haven’t finished it but thought you would like it because it deals with your theme. Thanks for your thoughtful piece. Let’s all pause, take a deep breath and don’t forget to cherish the otters.