As the saying goes, it takes a village to raise a child. In the latest novel from Brazilian-American author Marcelo Antinori, it takes a village to protect the loved ones of a fallen guerrilla fighter who has been declared dead three times. And behind that enigma lie even more precious and remote secrets, including – perhaps — the location and real meaning of the fabled city of El Dorado, which has been protected with the lives of generations of Indigenous people.

As the saying goes, it takes a village to raise a child. In the latest novel from Brazilian-American author Marcelo Antinori, it takes a village to protect the loved ones of a fallen guerrilla fighter who has been declared dead three times. And behind that enigma lie even more precious and remote secrets, including – perhaps — the location and real meaning of the fabled city of El Dorado, which has been protected with the lives of generations of Indigenous people.

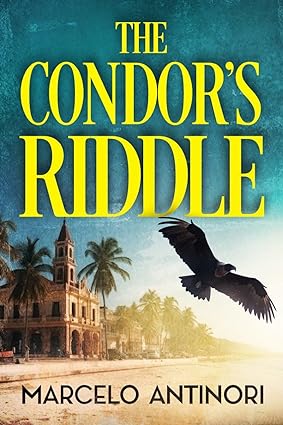

An entire society of expatriates and eccentrics is brought to life in Antinori’s newest tale of international intrigue, The Condor’s Riddle, which populates the mythical port of Santa Clara by the Sea with a rogue’s gallery of heroes and antiheroes. Caught between the inexorable pincers of the Chinese and American embassies, along with the heavily armed drug cartels who demand answers about the dead man, the endearing cast of characters struggles to stay alive and safe in their marginal but customary way.

One of the indispensable band of friends is Bebéi, a naïve and simpleminded French archivist with a photographic memory. His guileless, camera-like observations become indispensable to solving an ever-deepening mystery and calming the streets. His investigative work is assisted by a Caribbean ex-president who lives among cats; a Chinese exotic dancer with a doll face; a Rastafarian workaholic; a Greek sea captain; even a remorseful German terrorist, who shares a vagabond life on the church stairs with a runaway Wall Street investor and a stoned Canadian hippie. Threading in and out of the narrative is a blind indigenous child who “sees” and senses much more than the sighted adults around her.

Says Antinori: “I aim with my novels nothing more than to entertain readers. The Condor’s Riddle was written in the old town of Panama City. I can swear that all characters, no matter how bizarre, eccentric, and lunatic they might look, were my daily companions on walks around the city.”

Regarding Latin American literature in general, he continues: “Religious immigrants did not build South America; our ancestors were ambitious irresponsible dreamers. It’s in our DNA and our stories. It doesn’t matter if they were revolutionaries, drug dealers, drunkards, or prostitutes; they all spit blood, have a stinky sweat, cry tears, and laugh as if nothing else matters. That’s what you will read in The Condor’s Riddle.”

According to Kirkus Reviews, “Antinori has crafted a vigorous, detailed, and delightfully quirky tale filled with scene after scene of detailed developments and an author’s confident prose determined to amuse and entertain.”

That there are strong elements of magical realism in The Condor’s Riddle is no accident. Antinori notes that “I was raised reading Garcia Marquez, Vargas Llosa, Borges, Amado, Puig, and Cortazar. What else could someone wish to write after that?”

The Condor’s Riddle is merely one of his answers – with more to come.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.