By the time Andrew Hamilton reached the Eastern Shore in 1708, Chestertown was well on the way to becoming a prosperous Royal Port, just two years after its founding.

For a 32-year-old attorney, the era was a rich mine of opportunities: land and shipping contracts, tobacco, town charters, boundary disputes, all the growing pains of a wealthy merchant class town.

Hamilton, a Scottish immigrant, first landed in the Virginia colonies, where he learned law and taught classics while building his reputation as a brilliant lawyer. It took him little time to establish a law practice in Chestertown after purchasing the 600-acre farm “Henberry,” an area we know as the town of Millington while keeping property—and clients— in Virginia.

Hamilton, a Scottish immigrant, first landed in the Virginia colonies, where he learned law and taught classics while building his reputation as a brilliant lawyer. It took him little time to establish a law practice in Chestertown after purchasing the 600-acre farm “Henberry,” an area we know as the town of Millington while keeping property—and clients— in Virginia.

1712 was a watershed year for the attorney. He left for England and joined Gray’s Inn, one of London’s prominent societies for barristers. The society’s membership included Francis Bacon, and William Cecil, advisor to Queen Elizabeth I and proponent for the execution of Mary Queen of Scots.

Hamilton was admitted to the Bar, a necessary accreditation for practicing law in Britain. That same year William Penn hired Hamilton in a replevin case whereby the seized goods, in this case property, were returned to the owner until the case outcome. Penn was impressed with the colonial barrister, and Hamilton would go on in Penn’s service when he returned to Pennsylvania to tend to his friend’s many business interests.

For the next 17 years, Hamilton practiced law in Pennsylvania, but it would be a New York case in 1730 that would anchor his legacy as “The Philadelphia Lawyer.”

At that time, New York’s governor was William Cosby, a greedy, jealous, petty tyrant who lived up to one historian’s assessment of colonial governors as “often being members of aristocratic families whose personal morals, or whose incompetence, were such that it was impossible to employ them nearer home.” Cosby had already fired the Chief Justice of New York for deciding a case against him and justified his decision in the New York Weekly Journal, printed by one of two printers in the colonies, John Peter Zenger.

Scathing satires and controversial editorials written under pseudonyms were fired back at Cosby. Cosby had none of it and had Zenger arrested on charges of seditious libel, a holdover from Henry VIII’s Privy Counselors of Star Chamber. Dare to criticize authority with the truth, go to prison. Zenger spent ten months in prison awaiting trial, never revealing the authors of the editorials and satires. At the same time, his wife kept the press running, only missing one edition of the paper.

Cosby used the State Supreme Court, minus the Chief Justice he fired, had two attorneys defending Zenger disbarred, and appointed a pro-Cosby public attorney to the printer.

Things took a Perry Mason turn. Zenger’s remaining attorneys arranged for Andrew Hamilton, “the lawyer from Philadelphia,” to take over the defense. Ne accepted the job for no fee.

What happened next planted the idea of freedom of the press.

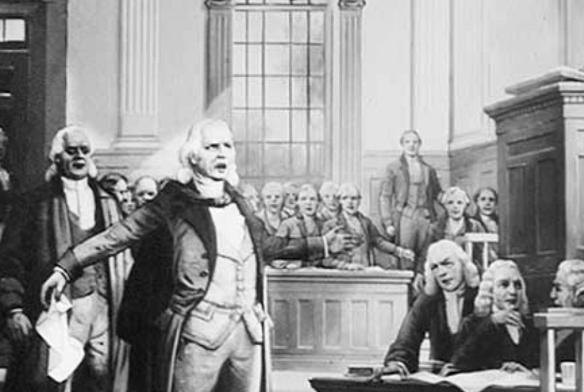

Hamilton addressed the jury attending the trial, admitting that Zenger had printed the editorials, but the Crown would be required to prove that they were false statements.

“The question before the Court and you, Gentlemen of the jury, is not of small or private concern. It is not the cause of one poor printer, nor of New York alone, which you are now trying. No! It may in its consequence affect every free man that lives under a British government on the main of America. It is the best cause. It is the cause of liberty.”

In other words, the truth is the best defense against libel. “The laws of our country have given us a right to liberty of both exposing and opposing arbitrary power (in these parts of the world at least) by speaking and writing truth,” he said.

The judge, however, ordered the jury to dismiss Hamilton’s plea, adhere to the current laws of sedition and convict Zenger for printing the editorials.

The jury, convinced by Hamilton to judge the law of the case rather than Zenger’s action as a printer, took ten minutes to return a “not guilty” verdict. It became one of the most famous cases of a jury nullifying a standing law.

Decades later, one of the Founding Fathers, Gouverneur Morris, wrote that the case was “the germ of American freedom, the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionized America!” His grandfather was the judge dismissed by Cosby at the outset of the Zenger trial.

In 1964, U.S. Supreme Court cited the Zenger case in its landmark free-press decision of New York Times v. Sullivan, a dispute over a full-page ad by supporters of Dr. Martin Luther King. The ad criticized southern officials for violating the rights of African Americans. The Court said that the Zenger case showed Americans valued the right to complain about the government and their leaders.

If it weren’t enough for Hamilton to have planted the seeds for the First Amendment of the Constitution, the “Lawyer from Philadelphia” had another interest: architecture. Look no further than his design for a building in Philadelphia that would come to be known as Independence Hall, the site of the 1787 Convention that created the United States Constitution.

“Truth does not matter” is not a new dictum. It’s an age-old flag hoisted by kings, authoritarians, and insurrectionists now flaunted in a post-factual era of fake news, alternative facts, and the push to exhaust critical thinking. Whether or not we have the spirit and ability of Alexander Hamilton to reset the guardrails for the truth to matter remains to be seen.

Vic Pfeiffer says

What a great history lesson and so timely in our current environment. “Men”/people of character – one in this case standing out, but many in ours – to uphold the tenents of our democratic institutions & norms are needed, and that’s all of us in our own small and large ways.

Michael H McDowell says

And the National Press Club in Washington DC has a meeting room named after Peter Zenger.

Cl Ra says

Fantastic article. Enjoyed learning something new. Thank you!