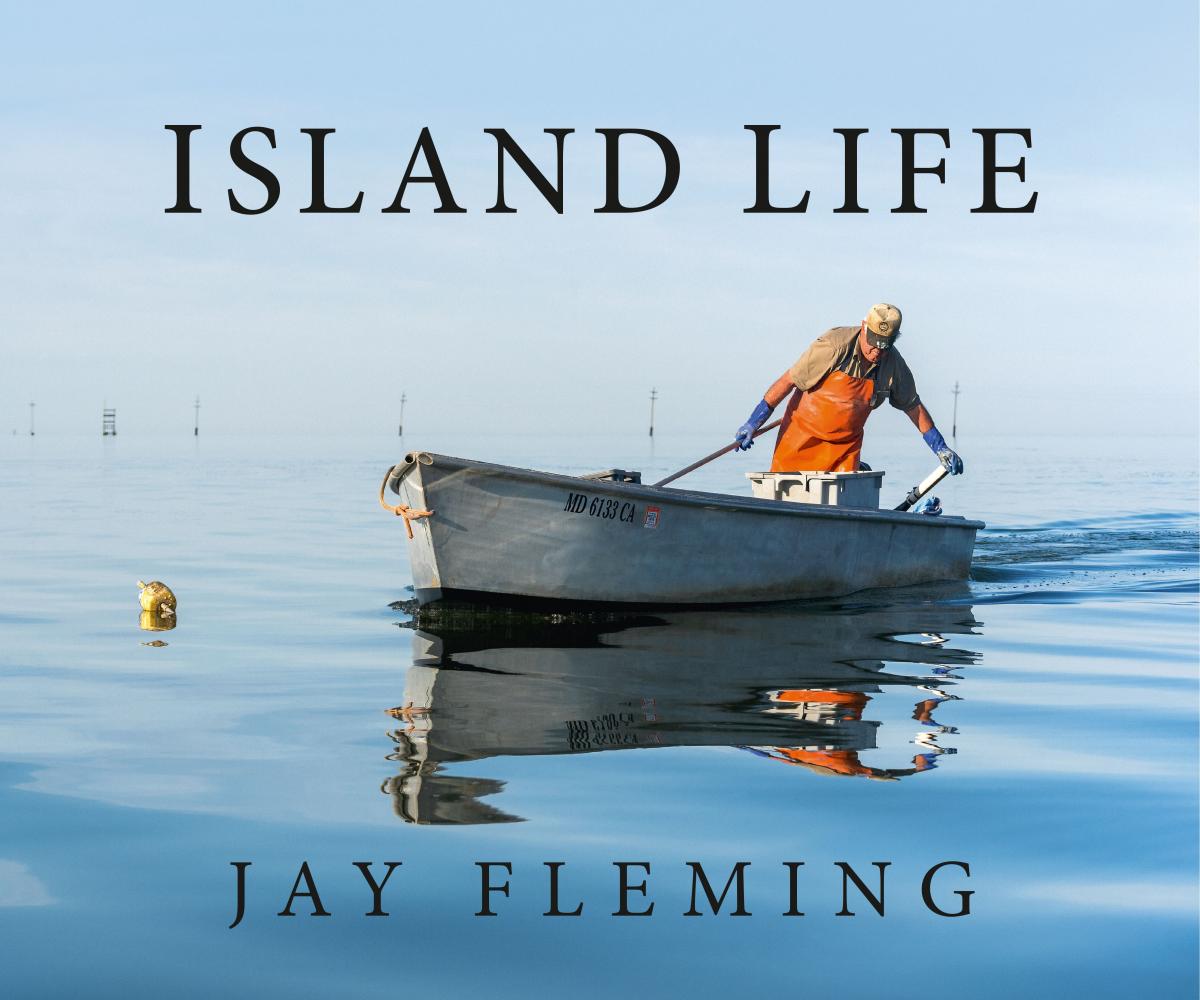

Editor’s note. It is with profound sadness that we must note that Dwight Marshall, a central figure of Jay Fleming’s book and whose photo graces its cover, passed away as he was working on the water yesterday. The Spy has decided to publish Jeff McGuiness’ article of Jay’s work today as a tribute to Dwight, his family, and their remarkable contributions to our Chesapeake Bay heritage and culture.

Its title deceptively simple, Jay Fleming’s magnificent new book, Island Life, uses brilliant photography to address a fundamental issue of our time, dealing with overwhelming change while joyously appreciating the beauty surrounding us as we do. His photographic essay is so moving that ever since I saw the book’s proofs, I’ve had a recurring dream that is a metaphor for what our lives have become.

I wake up in our home in St. Michaels with unsettling images of a vanished life. I am walking through the home we left in Northern Virginia that was torn down by a developer, a house in acres of woods that was part of a land of pastoral farms in verdant fields of clover that became cloverleafs, shopping centers, mega developments, and office towers, all within a thirty-year span. As I open my eyes, I wonder what the dreams are of those who live a few feet above sea level on the distant islands of Smith and Tangier in a remote part of the Chesapeake. Do they sleep with images of the heaving waters around them, the enormous skies of the lower Bay, workboats disappearing in the shimmering haze of summer, winter gales sweeping over the frail soil, the land underneath gnawed away by salt water?

These islanders and those that came before them live with that water constantly in sight, a still pond one day, a sea surging past their doorsteps the next. They trace their heritage to those who emigrated from Cornwall, Devon, and Dorset in southern England in the 1600’s after the death of Queen Elizabeth I. Their ancestors settled along the shore and on the islands of the lower Chesapeake, planting crops and drawing sustenance from the area’s bountiful waters which, unlike the privations faced in other New World settlements, made starvation impossible. Their descendants have lived on these islands for eight to ten generations, first primarily working the land, then as fortunes changed, moving onto the water. Those who have remained on the islands prefer the slower pace of life, separation from what our world has become, the intimacy with elemental forces.

During the War of 1812, the British Navy used Tangier as the base from which they sacked America’s new capital and burned its White House. After returning for a two week break before heading to Baltimore to continue their mayhem, the British asked Tangier’s leader, Joshua Thomas, to “exhort the soldiers” during a ceremony as the marines and sailors prepared to board the fleet. Thomas chose instead to tell the troops that they were making a big mistake, that they would “not succeed,” that Baltimoreans were different from Washingtonians, and that they should “prepare for death.” What prescient message can those distant souls on Tangier and Smith give us mainlanders struggling with life today?

For decades, tourists from metropolitan areas have traveled by boat to this separate world to gawk at the locals and listen to their unusual dialect before smugly returning to the security of their well-ordered communities. Then the Pandemic hit. Those communities emptied as Americans roamed about searching for a different, less vulnerable place to live. For decades, Smith and Tangier have been the target of requiems and elegies from mainlanders focused on the Chesapeake’s waters slowly overtaking the islands’ shores. The writers ask, often condescendingly, don’t you people know what is going to happen to you? Now the islanders can ask, don’t you know what’s happening to you because of the consequences of your hypergrowth? Are you prepared to deal with it? The lesson of COVID is that no one is immune from unexpected change, so the question is, how to do we survive, prosper, and find happiness amid uncertainty?

Island Life is Jay Fleming’s answer. He burst onto the Chesapeake Bay photographic scene five years ago with his first book, Working the Water. We were immediately captivated by his boundless energy and infectious enthusiasm. Never before had we seen someone grinning ear to ear while immersed in a pound net full of fish so things could be photographed from the point of view of the captured. In a world saturated with photographs of the Chesapeake, Fleming’s vivid colors, unusual perspectives, and bold, simple designs set him apart. Soon his work was hanging in galleries, featured on magazine covers, and displayed in design houses. The book, now in its fourth printing with nearly ten thousand copies, is an achievement for someone who is his own publishing house.

Working the Water is a magnificently illustrated guide to everything that goes on in Chesapeake waters—fyke netting, haul seining, gill netting, crab scraping, bank trapping, pound netting, crab potting, and purse seining, for example. It is required reading for any Chesapeake boater not involved in commercial fishing. No more puzzling over what all those flags, floats, and poles are as they slide past your stern.

Island Life goes in a different direction. It is a story of resilience in a world both beautiful and haunting. Unusual marine life in green water harvested in challenging conditions that becomes a delicacy on a dinner plate hundreds of miles away. The making of Mary Ada Marshall’s Smith Island cake, the iconic Maryland state dessert she ships from the edge of the world all over the east coast. A nesting colony of brown pelicans in tall grass hovering over their hatchlings who will soon be able to fly in formation a few feet off the water searching for menhaden. But it is Fleming’s oneness with the lives of the islanders and his depiction of their strong sense of community produced by their isolation and the challenges of their unique way of life that makes the book so distinct.

Mary Ada Marshall shipping her Smith Island Cakes from her dining room on Smith Island. Dwight Marshall is behind her in their living room.

Over the past few years, Fleming has spent months on Smith and Tangier working on his photography and conducting workshops to the point he is no longer an outsider looking in. He is an island waterman in his own right, piloting his center console Privateer, a photographic platform custom built by Mary Ada and Dwight’s son, Kevin, as he documents who the islanders are and what they do. His is a studied observation that has created a connection, a bond, with these god-fearing souls that allows him to see life through their eyes, feel the water’s unpredictable grip, and dream the dreams they dream. Yes, the islanders live amidst fierce forces as they have for centuries, but so now do we all, and the way he shows how they see the wonder of life while living along peril’s edge can be a guide for all of us on the mainland.

Of the dozens of photographs in Island Life, the one that knocked me off my chair shows Darlene and Morris Marsh in their home in Ewell on Smith Island. Morris is seated comfortably in their living room reading the Bible next to a Christmas tree decorated with American flags. Why the flags? Because the Holiday season has not yet arrived. Darlene is in the foreground looking directly at the camera. And what is she doing? Holding a knife while picking crabs. Now, most people who pick Chesapeake crabs are appropriately attired for the collateral damage that occurs when crustaceans are dismembered. Darlene is dressed as if she is about to go out for the evening. She would look no different if she were using the knife to butter a dinner roll at a church social.

When I first saw this image, I was reminded of Grant Wood’s American Gothic, the iconic painting that hangs in the Chicago Institute of Art depicting a middle-aged couple standing in front of an Iowa farmhouse in the early years of the Depression. He holds a pitchfork while she, primly dressed, looks prepared to deal with any challenge thrown her way. American Gothic has come to be regarded as one of the finest representations of resilience, fortitude, and dignity in the face of mounting hardship on the early twentieth century prairie. If the Baltimore Museum of Art is searching for the twenty-first century Chesapeake equivalent, Jay Fleming’s image of the Marshes of Smith Island is worth consideration.

Island Life will be released in November. It is available for purchase on Jay Fleming’s website and will soon be available in book shops, museums stores, and art galleries throughout the Chesapeake region. The Trippe Gallery in Easton, MD, will hold a book signing for Jay on Saturday, November 13, 2021, as part of Waterfowl Festival.

Jeff McGuiness was the senior partner of a public policy law firm based in Washington, DC, and founder of HR Policy Association. A fine arts major in college who served as a photographer in the Air Force during the Vietnam War Era, he has picked up where he left off 50 years ago with Bay Photographic Works. He lives in St. Michaels, MD.

Jamie Kirkpatrick says

Jay has been a generous contributor to The Spy’s Chesapeake Lens Project. His body of work is truly superb.