Putting down a book after reading its final page is usually just that. Done. What’s up for dinner? Finishing American Ramble: A Walk of Memory and Renewal by Neil King Jr. due out April 4 from Mariner Books rearranged my universe. It brought me into a new dimension, one in which I could see and appreciate everything around me more vividly and with greater compassion and comprehension. That sounds a lot like a religious experience, and perhaps Ramble is, because something changed in me fundamentally for having read it.

That feeling was doubly odd, because I had pored through three previous drafts of Neil King’s book as well as a daily blog that was the foundation for its development. Shouldn’t the published version have been déjà vu?

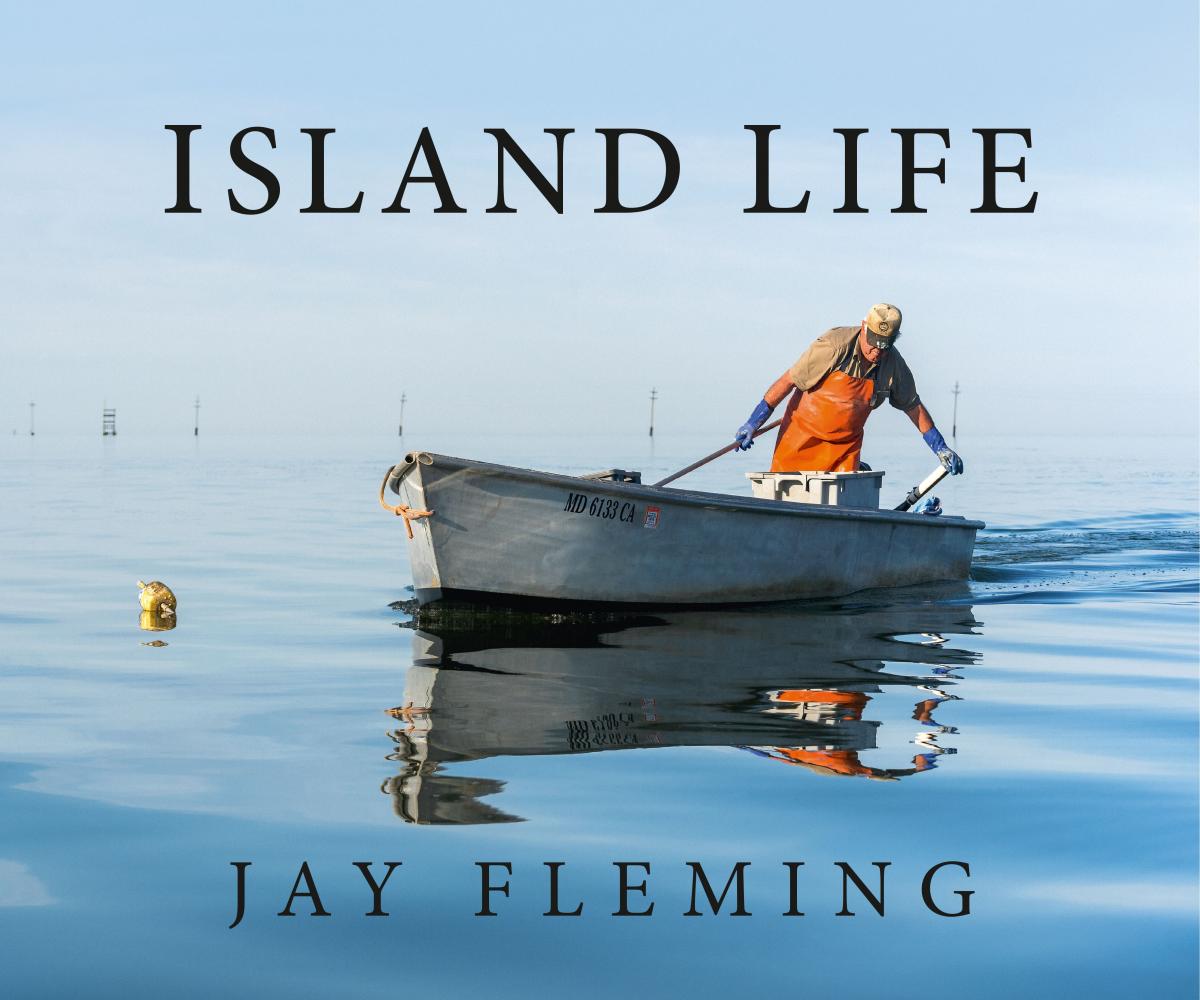

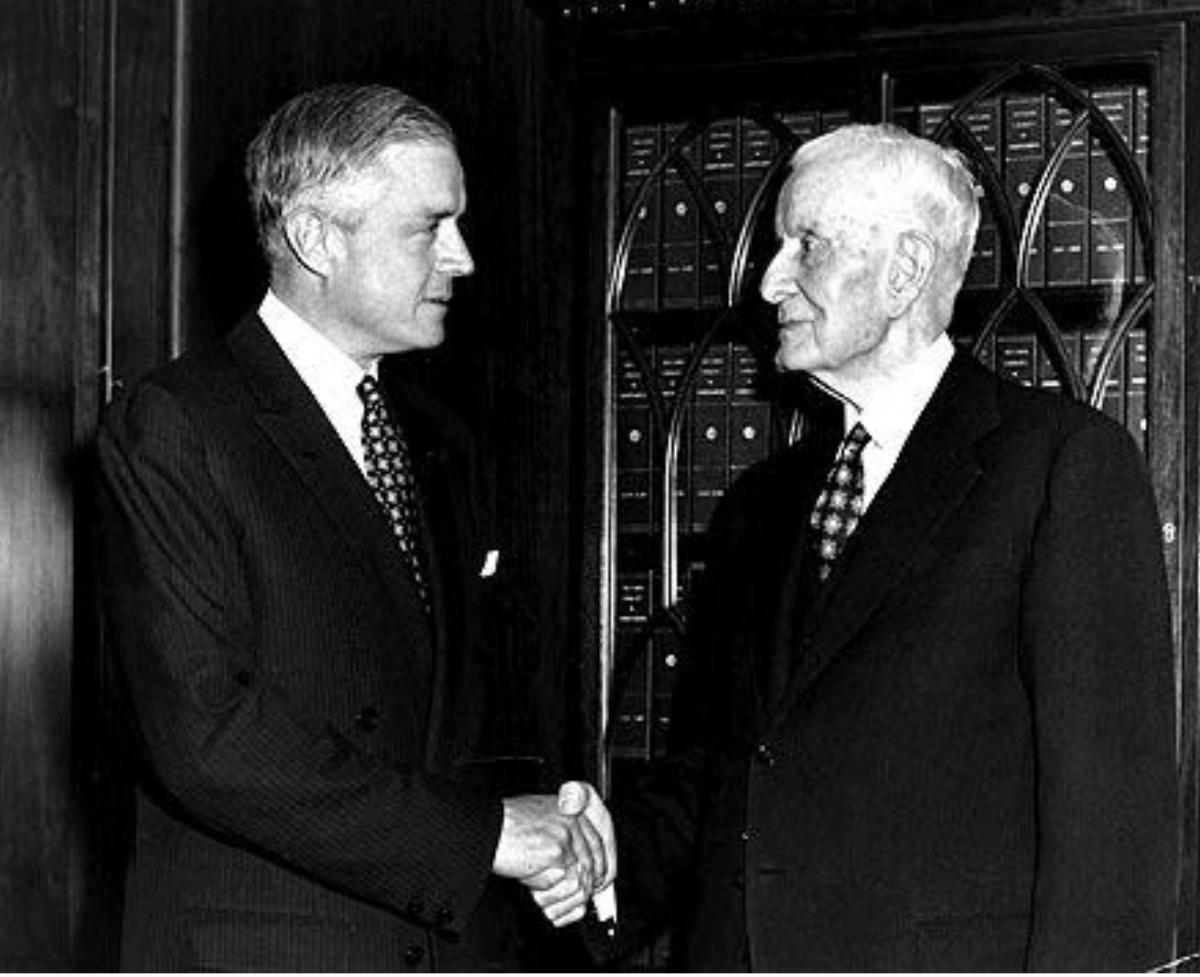

I first met Neil two years ago on a cold January morning while being driven around a farm near Claiborne, Maryland, by George Hamilton. George would go on to do the beautiful pen and ink drawings that illustrate American Ramble. I was looking for shots I could use in a photographic essay when a raspy voice rumbled, “You the guy working on a Frederick Douglass book?” George introduced me to the former global economics editor of the Wall Street Journal whose byline I had relied on for years in my policy work in Washington, DC. The Neil King Jr. in my mind was someone short like myself. To my surprise, towering over me was a rail thin figure on the legs of a heron. That started a conversation in the 25-degree weather that had five themes running simultaneously until George said enough—and drove us away.

It turned out that this journalist was working on a book of his own, one in which he would walk out the front door of his home on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, and keep walking until he ended up in The Ramble in New York’s Central Park. His path would be “a shallow arc through the founding territory of our nation, its original heartland.” It would be an easy walk along a “swath of the country that most travelers want to put behind them.” His plan was to “poke among the graveyards of our past and brush the moss off forgotten things.” He would “to talk to America, listen to her, examine her, to wonder over her.” Neil accomplishes far more than that in American Ramble.

Since that January morning, I have discovered that Neil King is a gifted writer and exceptional intellect. He must have been that unusual guy in college who operated in a different reality, the one who couldn’t fathom a secure, pedestrian life, the type of student for whom schoolwork and struggle are disassociated terms, the free spirit who quits college to work his way around the world and begins by buying a one-way bus ticket to Laredo because he likes the sound of it.

Along the way Neil spent a month in Sri Lanka in a Buddhist monastery but couldn’t get with the program. Later, he went off to Eastern Europe as the Iron Curtain was falling with no real job prospects and landed on his feet as a reporter. With that Kerouacian training, Neil ended up at the most traditionally conservative, buttoned-down newspaper in America writing this trenchant lead sentence in the Journal’s lead story on September 12, 2001, that led to a Pulitzer: “By successfully attacking the most prominent symbols of American power—Wall Street and the Pentagon—terrorists have wiped out any remaining illusions that America is safe from mass organized violence.”

There is a reason I heard a raspy voice that morning. A tick had nailed Neil with Lyme disease, and the man with the FM radio voice lost one of his vocal cords. His immune system had been compromised because of two excruciating bouts with cancer for which the initial prognosis was not good, terrible actually, yet Neil now brims with life, energy and yes, gratitude. He is, as he writes, not in the clear but in a “wide clearing with the forest too far away to see.” Speaking the language of the New Testament, he testifies that his “cleansing began the morning a doctor first uttered the word “cancer” and the trees on the way home impressed me as trees had never before.” His walk of renewal taught him “to bear witness in the most fundamental way. To marvel and behold. To take it in. To be present in a way that tilts toward rapture.”

American Ramble is not a walk up I-95. His path is along the backroads of the Mid-Atlantic discovering distinct regions he characterizes as Capitolia, Southlandia, Englandia, Anabaptistan, Presbyteriana, and Amazonia. He moved through them “in a meditative trance, a space both expansive and entirely my own.” He left “the day open as to what path I would take or what I would see along the way.” But this is not a casual saunter. “For more than a year I had studied the old maps and read the travelogues, this history of the early settlements, the injustices and travesties and triumphs, the decimation and then regrowth of its flora and fauna.” With Neil’s flair for identifying, attracting, and reveling in the offbeat, we are given a master class on how America was really formed and what we have become.

A few weeks ago, Neil sent me and our mutual friend Charlie Yonkers the link to his promo video. My petty interest in watching it was to see if he used any of my photographs. Charlie, who has a more expansive thought, focused on a book Neil had in his backpack, Carlo Rovelli’s The Order of Time. That launched a discussion between the two that was over my head, but in subsequently listening to the Audible version, Rovelli propounds that our concepts of time and how it flows are flawed, that time itself disappears at the most fundamental level. In reading the published version of Neil’s book, I realized the extent to which it is structured around Roveilli’s thinking and Neil’s own view of time. He sees his journey as “the satisfaction of having completed something magnificent, of having stepped outside of time, however briefly.”

Getting from DC to New York along a meandering path takes a lot of steps, 330 miles worth in Neil’s case. He talks about his stride falling “just shy of three feet.” I found that my first step can be stretched to that length, but when my other foot comes forward, I fall over. With the colossal stride that is walking and then writing American Ramble, Neil found something we should all aspire to, “a rhythm, a stillness, that can transfigure whole days and elongate time. A buried beauty that resides right there on the surface, for all to see.”

More information on American Ramble: A Walk of Memory and Renewal and its author can be found on Neil King Jr.’s website which includes purchasing information. The site has a six-minute video which is beautifully done and even uses some of Jeff McGuiness’s photographs.

Jeff McGuiness is the author of Bear Me Into Freedom: The Talbot County of Frederick Douglass. He considers Neil King’s help with it invaluable.