Jacob Lawrence was born in Atlantic City, New Jersey in 1917. His parents Jacob and Rosa Lee Lawrence divorced in 1924. Jacob and his two younger siblings grew up in Harlem with their mother. She enrolled him in the Utopia Children’s Center, an arts and crafts settlement house in Harlem, to keep him busy. He learned to use tempera paint, a water based medium, which he would continue to use throughout his career. As a child, he copied the rug patterns in his house: “people of my generation would decorate their homes in all sorts of colors…so you’d think in terms of Matisse.” When his mother lost her job, Lawrence dropped out of high school before his junior year and joined the Civilian Conservation Corps, part of the New Deal, where he planted trees, drained swamps and built dams.

Returning to Harlem after his stint in the Corps, he enrolled in the Harlem Community Art Center, then under the leadership of African-American sculptor Augusta Savage. Impressed by Lawrence’s talent, Savage obtained a scholarship for him at the American Artists School and a paid job with the Works Progress Administration. Lawrence was able to continue making art, which he did at an astonishing rate. An important influence on his work was Professor Seifert, whom he met playing pool at the Harlem YMCA. Seifert had a large collection of books on African American history. He offered Lawrence the use of his books and encouraged him to go to the Schomburg Library in Harlem to read all he could about African and African American culture. He also took Lawrence to see the 1935 exhibition of African Art at the Museum of Modern Art.

Lawrence began his career with three series of works illustrating the lives of African American icons: “Toussaint L’Ouverture“ (1938) (41 images); “Harriet Tubman” (1938- 1939) (31 images); and “Frederick Douglas” (1939-1940) (40 images). The original “Toussaint L’Ouverture” series was created in 1938 with tempera on paper, but with age became fragile, and Lawrence recreated in the 1990’s fifteen of the original images in silkscreen. He recreated several images from many series in silkscreen in his later years

Raised as a slave on a plantation, Toussaint L’Ouverture had been educated and was literate. He was freed when he was given a position of trust as a carriage driver. He rose from there to become Commander-in-Chief of the Haitian army in service to the French. However he was aware of the horrendous living conditions of the black slave population, and led the slave revolt in 1800 against Napoleon Bonaparte’s occupying troops. He helped draw up Haiti’s democratic constitution. On August 29, 1793 Toussaint declared to the black population at St. Dominique, “Brothers and friends, I am Toussaint Louverture, perhaps my name has made itself known to you. I have undertaken vengeance. I want Liberty and Equality to reign in St. Dominque. I am working to make that happen. Unite yourselves to us, brothers and fight with us for the same cause. Your very humble and obedient servant, Toussaint Louverture”

“Deception, no. 13” (1997) (22’’x 34’’) (silkscreen) depicts the 1802 event when Toussaint was invited by French General Brunet to a parlay. It was a deception; Toussaint was captured and taken to Paris, where he died in prison in 1803. He is known as the “Father of Haiti.” Lawrence’s original title for the image of Toussaint from the 1938 series summed up his impressions of Toussaint and his achievements as “Statesman and military genius, esteemed by the Spaniards, feared by the English, dreaded by the French, hated by the planters, and revered by the blacks.”

Lawrence calls his style Dynamic Cubism. In “Deception” we see Toussaint attacked by five French soldiers, all with drawn swords. The colors are limited but effectively used. The black shapes of coats, boots, hats, chair, and wall panels surround and secure the edges and angle diagonally toward Toussaint. A brown floor panel in the center of the composition leads our eyes to the seated Toussaint. The remainder of the floor on which the soldiers stand is ochre in color, and it ends just behind Toussaint’s shoulders an effective contrast to the black and white uniforms of the soldiers. A dark green wall completes the room, and a small contrasting turquoise rectangle in the center of the wall effectively highlights Toussaint’s upper torso. By the position of his turned head we see the surprised look on his face. His is the only clearly seen face. Whether painted with brush and tempera or silkscreened, the of solid and simple, but elegant, shapes are easy to understand and highly effective.

Lawrence’s “Migration Series” (1940 to 41) (60 images) brought him to national prominence when it was exhibited in 1941 at the Downtown Gallery in Greenwich Village in New York City. Lawrence was the first African American to be represented by a New York gallery. The series was quickly purchased by the Philips Collection in Washington, D.C. and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Fortune Magazine ran an issue with 26 illustrations from the series, and the series was also published in 1941 in a book funded by the Works Project Administration. Plate No. 1 of the series was named “During the World War there was a great migration north by southern Negroes” (1938); however in 1993, Lawrence changed the title to read “During World War I there was a great migration north by southern African Americans” (1993). In this image we again see Lawrence’s use of limited but effective colors. African American figures flood toward the three bright orange doorways labeled Chicago, New York, and St. Louis. The scattered use of orange shapes throughout the composition begin at the bottom and are strategically placed to lead the viewer’s eye to the three doorways.

Lawrence continued his career creating such series as “John Brown” (1941-1942) (32 images); “Harlem”(1942) (30 images); “War” (1946-47) (14 image), during his service in the US Coast Guard during WWII; “Struggle? History of the America People” (1953-55) (30 images); “Great Ideas of Western Man” (1958); “Hiroshima” (1983) (8 images); and “Genesis” (1989), based on his memory of Sunday sermons given by Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Sr. at the Abbyssinian Baptist Church in Haarlem. Lawrence drew subject matter from his life and experiences in Harlem, from his extensive reading of history, and from his deep interest in current events.

“Men exist for the sake of one another. Teach them then or bear with them.”(1958) (21’’ x17’’) (oil on fiberboard) is a work from the series “Great Ideas of Western Men”. The title of this piece is a quote from Roman Emperor, Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, VIII: 59. A very large male figure of indeterminate race sits on a rock and is surrounded by children who reach out to him and listen to him. On first seeing the piece, we see three large black cracks running through the figures and the rock. After very close observation we see the man is holding a small tree with a root ball, ready to be planted. The title of the work tells us humans need to exist together, and we either need to be taught how to live together or to learn how to be tolerant of each other. The three tree branches create an interesting enigma; first they are hard to distinguish, and second they cross in front of the three of the figures as if creating divisions between the people and cracking the rock.

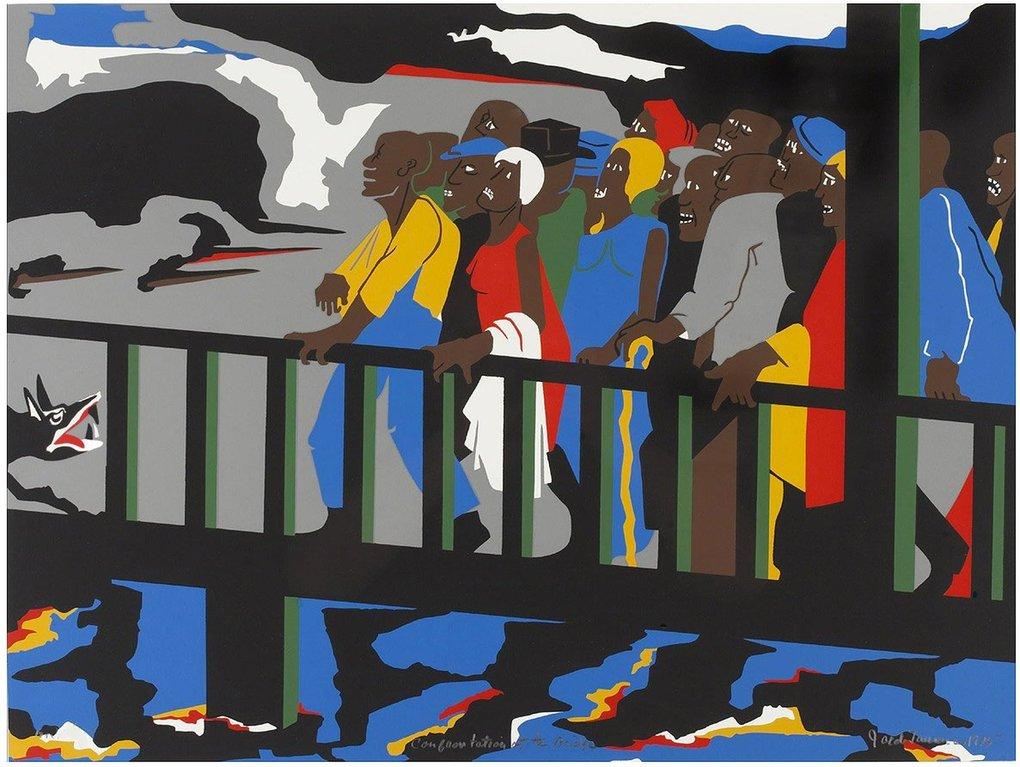

Lawrence was invited to create a work for the 1976 American Bicentennial celebration. “Confrontation at the Bridge” (1976) (19.5’’ x 26’’) (silkscreen) described the March 7, 1965, march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on route from Selma to the Alabama state capital in Montgomery. Led by Martin Luther King Jr., and John Lewis, the marchers were protesting for equal voting rights. To represent the brutal police attack, Lawrence has substituted a viscously snarling dog. Six hundred protestors were turned back. Lawrence does not elect to show the famous leaders of the march; he depicts instead the frightened mass of African Americans exerting their first amendment right to peaceful protest. Later in 1965 the US Congress passed and President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act.

In 1976 Lawrence added to the “Great Ideas of Western Men” series a piece titled “In a free government, the security of civil rights must be the same as that for religious rights. It consists in the one case in the multiplicity of interests, and in the other, in the multiplicity of sects.” a quote from James Madison’s Federalist Papers (1788). Lawrence’s works were carefully chosen to expose the viewer to vast set of images intended to be informative, educational, and thought provoking.

“Exploration” (1980) is a forty foot-long mural of porcelain and steel installed in the Blackburn Center at Howard University in Washington, D.C. The mural presents 12 consecutive images depicting the study of religion, political science, theater, law and agriculture, fine arts and philosophy, astronomy and music, medicine, math and history. Lawrence’s last commissioned public work “New York in Transit” (72 foot long, composed of Murano glass) was installed a few months after his death at the Times Square subway station.

Other Lawrence projects include children’s books containing his images. His first was Harriet and the Promised Land (1968), included in the list of that year’s best illustrated books by the New York Times and praised by the Boston Globe. Books John Brown and the Great Migration followed. He created a new series of work on eighteen Aesop’s Fables (1970) and another set of twenty-three Aesop’s Fables (1998). He was invited to participate in several community projects and received commissions from several private sources. Lawrence also taught at such prestigious institutions as Black Mountain College in North Carolina, The New School for Social Research in New York City, the Art Students League in New York City, the Pratt Institute in New York City, Brandeis University in Massachusetts, and the Skowhegan School in Maine. From 1971 until 1986, he taught at the University of Washington in Seattle.

After visiting Lawrence’s first exhibitions in 1938 at the Harlem YMCA, Charles Alston, one of his teachers wrote in an essay that Lawrence “has followed a course of development dictated by his own inner motivations…. Working in the very limited medium of flat tempera he achieved a richness and brilliance of color harmonies both remarkable and exciting…. Lawrence symbolizes more than anyone I know, the vitality, the seriousness and promise of a new and socially conscious generation of Negro artists.” Alston’s thoughts on Lawrence have proved accurate. Exhibitions of Lawrence’s art are numerous, and they continue to excite and enlighten us.

NOTE: The Mitchell Gallery, St John’s College in Annapolis is presenting free of charge an online exhibition of three of Lawrence’s series.

September 2 – October 6, 2020 -“Genesis” (1989) October 7 – November 1, 2020 – “Toussaint L’Ouverture” (1938, 1997) *******October 15, 2020: Online lecture “Toussaint L’Ouverture” series, FREE November 18 – December 18, 2020 -“Hiroshima” (1983) *******November 18, 2020: Online lecture “Hiroshima “series, FREE.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Jeanette Sherbondy says

Wonderful!