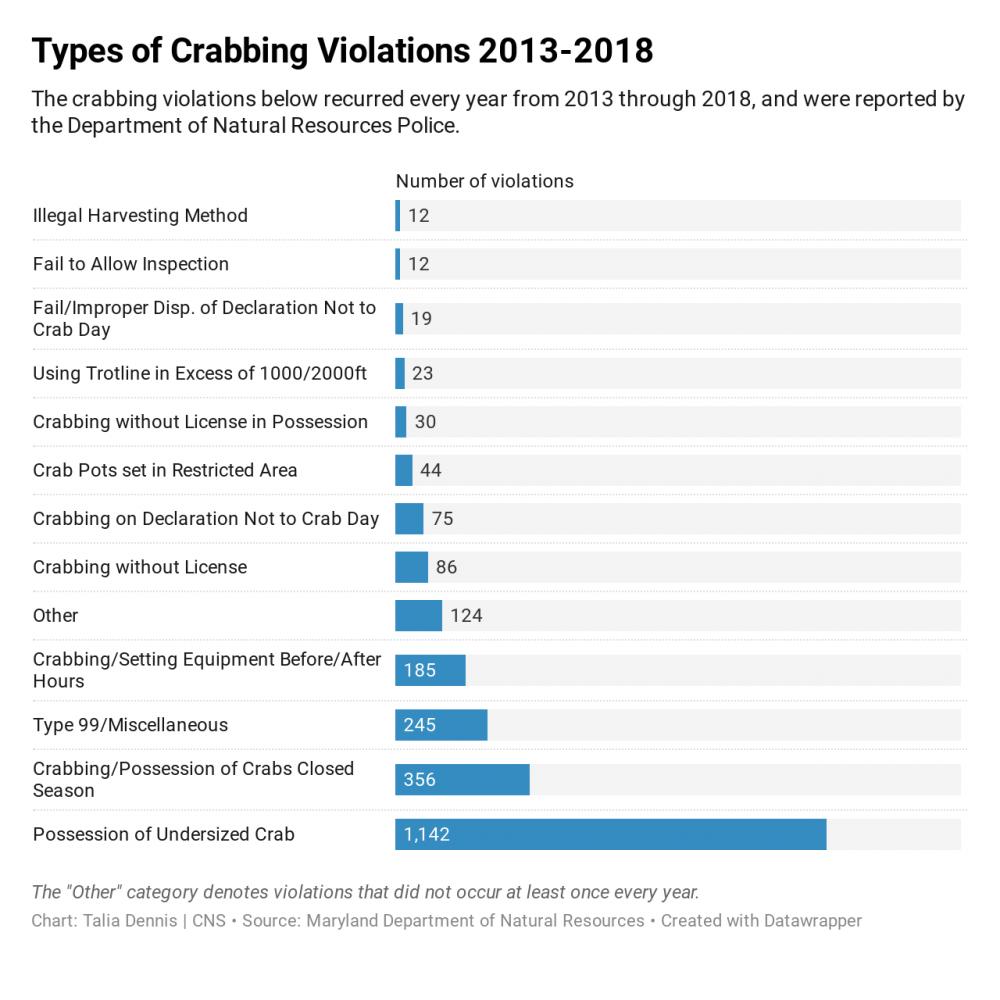

Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources reported 2,341 crab-related violations across the state from 2013 through 2018. There were 27 types of infractions ranging from undersized crab possession to illegal harvesting methods.

Possession of undersized crabs was the highest reported infraction and made up nearly half of the reported violations. Crabbing or possessing crabs during the closed season was the second most common offense with 356 reported citations during the six-year period. Crab season opens April 1 and closes Dec. 15, according to DNR’s eRegulations website.

Soft crabs must measure at least 3 ¼ inches, tip to tip on the spikes, throughout the season, according to eRegulations. Male hard shell and peeler crabs must measure at least 5 and 3 ¼ inches respectively. After July 14, the size requirements increase for both male hard shell and peeler crabs by a quarter of an inch.

Soft crabs must measure at least 3 ¼ inches, tip to tip on the spikes, throughout the season, according to eRegulations. Male hard shell and peeler crabs must measure at least 5 and 3 ¼ inches respectively. After July 14, the size requirements increase for both male hard shell and peeler crabs by a quarter of an inch.

“Officers are issued gauges for each size limit outlined by regulation,” said Lauren Moses, the public information officer for the Natural Resources Police. “If one or both tips [of the crab] fits inside the gauge, the crab is below the legal limit.”

Moses explained that live crabs illegally possessed at the harvest site are immediately returned to the water.

But the ones not discovered near the water are typically donated to a food bank or shelter, while rancid crabs are “disposed of properly,” she said.

There are some cases in which commercial watermen illegally possess the official state crustaceans in large quantities. Moses said Natural Resources Police sometimes sell adequately sized crabs to a dealer. She explained the money is held until a court rules it to can go to state general fund.

Moses noted that dealing with most crab-related violations is similar to speeding ticket procedures.

“The majority of citations are pre-paid by the violator, which is an admission of guilt,” she said. “Unless there is an error in the issuance of a citation or some other argument is made, all crab citations in which the violator did not admit guilt by paying the pre-set fine, are set for trial.”

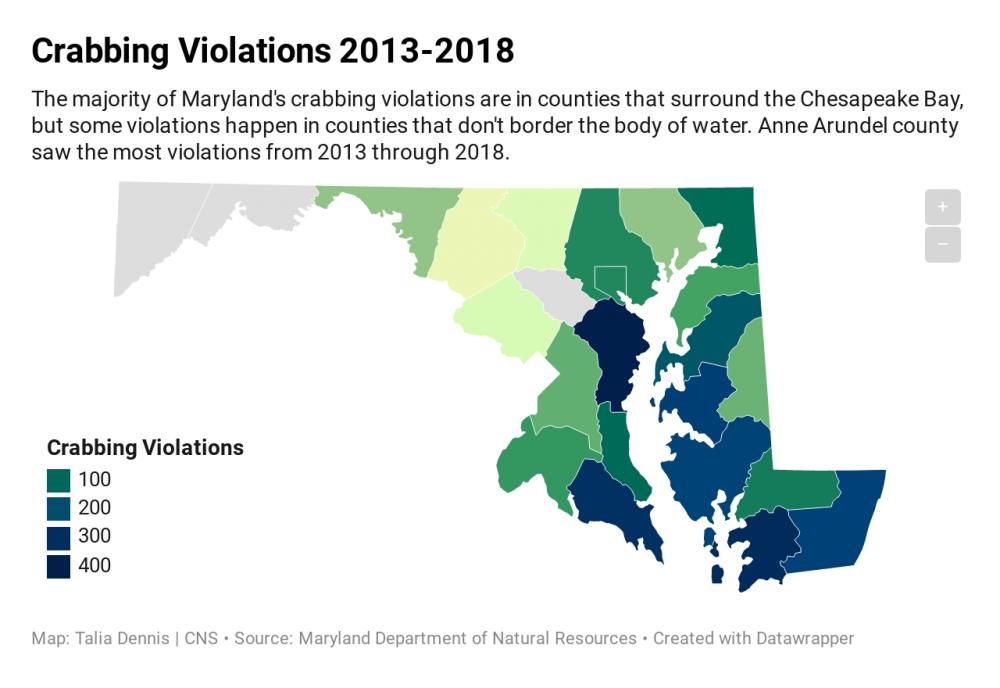

About 81% of all violations from 2013 through 2018 occurred in Anne Arundel, Somerset, St. Mary’s, Talbot, Worcester and Queen Anne’s counties — which all border the Chesapeake Bay. All 20 of the licensed crab processors in Maryland are located in these counties, with the exception of Anne Arundel County. However, the data does not conclude these businesses are the biggest offenders because it includes recreational and commercial violators. Only 1.2% of all offenses are by corporations or businesses, with nearly 40% of those violations reported in counties without crab processors.

About 81% of all violations from 2013 through 2018 occurred in Anne Arundel, Somerset, St. Mary’s, Talbot, Worcester and Queen Anne’s counties — which all border the Chesapeake Bay. All 20 of the licensed crab processors in Maryland are located in these counties, with the exception of Anne Arundel County. However, the data does not conclude these businesses are the biggest offenders because it includes recreational and commercial violators. Only 1.2% of all offenses are by corporations or businesses, with nearly 40% of those violations reported in counties without crab processors.

St. Mary’s County saw a steady incline of violations from 2013, rising from just 11 violations that year to 111 in 2018. It is an outlier in the data because many counties’ violation numbers peaked in 2016, with only a few seeing slight increases in 2018.

Moses named two possible causes for the spike in the county and in 2016. She said the overall increase in citations is “likely due to increasing our staffing and patrol efforts, or an increase in crabbers.”

The staffing growth allowed for more officers to be assigned to St. Mary’s County, which led to the increase in reported violations, Moses said. The average number of staff members at the department overall grew from 160 people in 2013 to 184 in 2016 — a 15% increase.

Less than 2% of the violations during the six-year period came from counties that don’t border a body of water suitable for harvesting crabs — Prince George’s, Caroline, Washington, Montgomery, Carroll and Frederick — and saw a combined 46 violations.

Some of these non-bay bordering counties have tidal waters home to crabs, but overall violations are not as prevalent as those with greater access to the Bay. Moses also indicated that commercial enterprises selling crabs and the vehicles transporting the catch are checked throughout the state.

“Officers conduct routine checks via police boat and on foot,” she said. “We check for any necessary license, the quantity of catch, the size of the crab, if there are sponge or soft crabs, and if the crabs are male or female.”

Routine patrol checks are conducted for both recreational and commercial crabbers, she said.

The upcoming years look to bring stronger efforts to police crabbing with the recent appointment of G. Adrian Baker as the department’s superintendent. Baker was the former Chestertown police chief. He rejoined the Natural Resources Police in September, after serving six years as the department’s central region commander until 2012, according to an August press release.

“He is focused on increased conservation enforcement that would include crab enforcement,” Moses said.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.