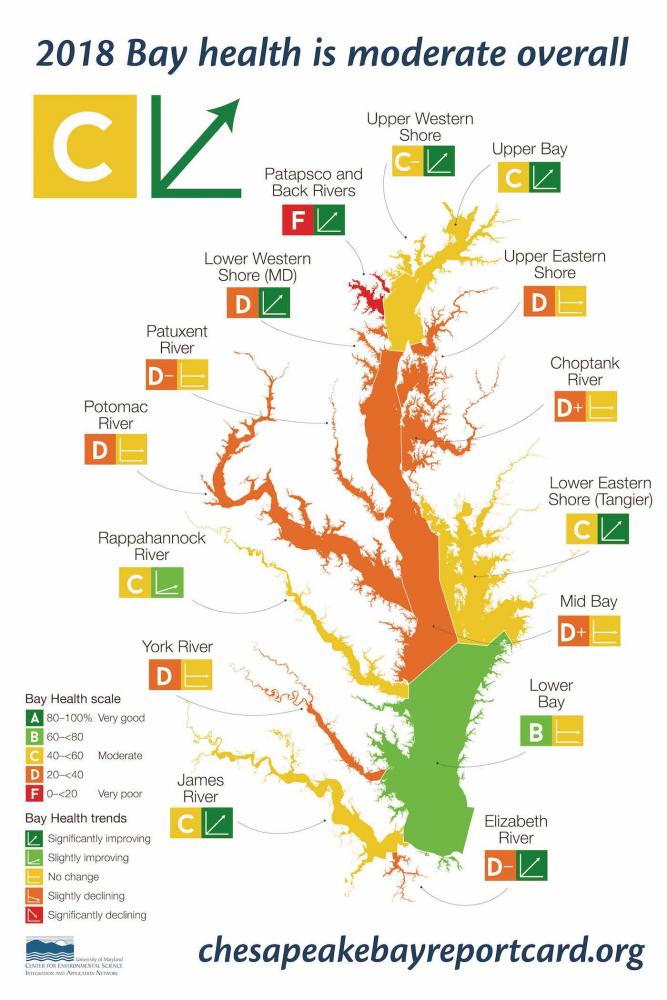

The Chesapeake Bay score decreased in 2018, but maintained a C grade, according to the 2018 Chesapeake Bay Report Card issued today by the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science (UMCES). This was due to extremely high precipitation over the year. Despite extreme rainfall last year, the overall trend indicates that Chesapeake Bay health is improving over time.

“While 2018 was a difficult year for Chesapeake health due to high rainfall, we are seeing trends that the Bay is still significantly improving over time. This is encouraging because the Bay is showing resilience to climate change,” said Bill Dennison, Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

Almost all indicators of Bay health, such as water clarity, underwater grasses, and dissolved oxygen, as well as almost all regions, declined in 2018. In particular, chlorophyll a and total nitrogen scores had strong declines due to very high rainfall causing nutrient runoff that then fed algal blooms. However, the overall Bay-wide trend is improving. Since 2014, all regions have been improving or remaining steady.

Almost all indicators of Bay health, such as water clarity, underwater grasses, and dissolved oxygen, as well as almost all regions, declined in 2018. In particular, chlorophyll a and total nitrogen scores had strong declines due to very high rainfall causing nutrient runoff that then fed algal blooms. However, the overall Bay-wide trend is improving. Since 2014, all regions have been improving or remaining steady.

“Our administration is pleased to see continued improvement in the health and resilience of our most precious natural asset, the Chesapeake Bay. Since taking office, we have been focused on improving the health of the Bay, investing a record $5 billion toward wide-ranging restoration programs. This report, along with the great news that Maryland’s crab population has grown 60%, is yet another promising sign of ongoing improvement of the Bay and that our continued investment is making a difference,” said Maryland Governor Larry Hogan.

Of the many factors that affect Chesapeake Bay health, the extreme precipitation seen in 2018 appears to have had the biggest impact. The Baltimore area received 72 inches of rain in 2018, which is 170% above the normal of 42 inches. As a result, the reporting region closest to Baltimore—the Patapsco and Back Rivers—saw a decline in health, decreasing to an F grade in 2018. The strongest regional declines were in the Elizabeth River and the Choptank River. The two regions that remained steady were the Lower Bay and the York River.

“The extreme precipitation in 2018 was a key issue, and current science shows that with climate change this area is going to be warmer and wetter,” said Peter Goodwin, President of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. “The Bay is in fact showing resilience in the face of climate change and extreme weather events, underlining that the restoration efforts must remain vigilant to continue these hard-won efforts.”

Fish populations received a B grade, showing a steep decline from the previous year’s score of A. Striped bass numbers sharply declined in 2018, while blue crab and bay anchovy scores declined somewhat (although blue crab are showing a revival in early 2019). These drops in scores are a cause for concern as smaller populations could lead to further declines in the future.

“This is not the time to put the brakes on efforts to restore the Chesapeake Bay. Our progress has been hampered by extreme weather events, but we must keep fighting,” said U.S. Senator Ben Cardin. “The health of the Chesapeake Bay depends on all of us in the region—federal, state, local, and private partners—working together toward a common goal: the preservation and restoration of the watershed, which in turn ensures better health for our citizens, economy, and local wildlife.”

“Improving the health of the Bay doesn’t happen overnight, or even in a month or a year. We must be constantly vigilant in our efforts to restore the Bay, and that starts with providing adequate funding for the Chesapeake Bay Program and other cleanup efforts,” said U.S. Senator Chris Van Hollen. “I will continue working through my role on the Appropriations Committee to prevent attempts to cut funding and to provide the Bay with the resources it needs to thrive.”

Actions that individuals can take to contribute to a cleaner Bay include reducing fertilizer use from all sources, carpooling and using public transportation, and connecting with people across the entire Bay Watershed to work together.

This is the 13th year that the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s Integration and Application Network has produced the report card. It is the longest-running and most comprehensive assessment of Chesapeake Bay and its waterways. This report card uses extensive data and analysis which enhances and supports the science, management, and restoration of the Bay. For more information about the 2018 Chesapeake Bay Report Card including region-specific data, visit chesapeakebay.ecoreportcard.org.

View The Chesapeake Bay Report Card here.

s mybay says

What did the Conowingo Dam report card look like?????