I’m looking forward to presenting some of my photographic images at the Trippe Gallery exhibit in Easton for the month of August. Owner Nanny Trippe, invited me, along with her daughter, Charlotte, to present a joint exhibit we have titled, “The Eyes of Three Generations.” We call it that because one of us is young, one, middle aged and the other is, well, old.

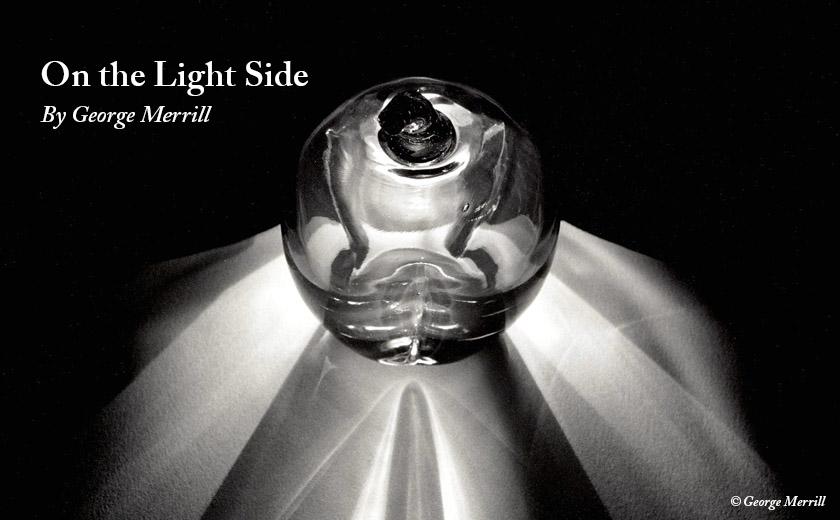

Light promises us its magic when streamed through the lens of a camera, capturing the light on tiny silver halides and transforming them into images. I’ve enjoyed this promise for seventy-one years.

In 1839, the famous mathematician, astronomer and chemist, Sir John Herschel, exclaimed, “It’s a miracle!” when first seeing a Daguerreotype. He was smitten. “They surpass anything I could have conceived.” He thought photographs would replace painting. French essayist Baudelaire wasn’t about to sit still for that. Instead, he lamented the rise of photography by commenting, “From that moment onwards, our loathsome society rushed, like Narcissus, to contemplate its trivial image on a metallic plate. A form of lunacy, an extraordinary fanaticism took hold of these new sun-worshippers.”

And this long before selfies.

In my opinion, Baudelaire was an unregenerate luddite and a snob. He spoke with forked tongue. Since 1685, when the monk Johann Zahn invented the Camera Obscura – the precursor of the modern camera – artists have used primitive cameras regularly as an aid to painting and architectural drawings.

I’ll allow that Herschel may have been over the top in his enthusiasm.

Icons of early photography report almost to a person about the rush of excitement, the thrill photography afforded them. Jacques-Henri Lartique, at age seven, took his first photos. His camera was a simple box with a cork for a shutter which he inserted or removed to adjust exposure. It was cumbersome as the box had to be secured to a tripod. He said of his first photographic adventures: “It’s marvelous . . . nothing will ever be as much fun.”

Renowned French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson took candid shots of people doing what people do; which is just about anything. He was unobtrusive, almost furtive in his photographic sorties and yes, on occasion he wore an oversized overcoat. He secured black tape to the chrome of his Leica’s to make them less visible so no one would realize that they were being photographed. The “right time” was his guiding mantra. There is a decisive moment in life when, he believed, circumstances conspire to create a once-and-for-all scenario. He sought to capture such ‘decisive moments’ or, as he put it, “[You] I want to catch the whole world in that tiny box . . . details that live up to life.”

“There’s an excitement about using a camera that never gets used up,” Edward Steichen said at 94. Steichen took his first photo when he was sixteen and photographed actively up until his death in 1973.

In his last years, Steichen planted a Shadblow tree in his yard in Connecticut. He photographed it seasonally in all kinds of weather, documenting its growth as we might take baby pictures. Reflecting on the magic of photography, he wrote, “I was coming to realize that the real magician was light.”

No doubt, but that the magic of photography is the light.

I know that same rush of excitement many of my photographic forebears did. In my early career, orthochromatic films could be developed with a safelight. In the darkroom, watching images emerge dimly on the negative was like standing by a mist-covered valley at first light anticipating a sunrise. Initially nothing is differentiated; all you see is a milky blur. Then, as the developer does its work, it’s as if the sun had begun burning off the mist, and the contours of the landscape slowly reveal themselves. I’d feel a rush of delight every time I’d see this as if I, like God, had wrought a world into light from the void of darkness.

Many of the chemicals used in early photographic processes were lethal. Before their toxicity was known, some photographers succumbed, if not to death, to madness by exposure to mercury vapor, lye and silver nitrate. I don’t know whether this phenomenon contributed to an interest in photographing corpses, but the practice was in fashion for a time. This would certainly have addressed photography’s early problem of having the subject remaining still for the protracted exposures then required, some as long as an hour. After the legendary shootout at OK Corral, some members of Clanton and McLaurin clans were photographed posthumously, appropriately in Tombstone, Arizona.

I developed Metol poisoning. Metol is a toxic agent found in developing formulas. When I started developing pictures it never occurred to me to wear gloves. In a few weeks, a rash developed on my hands and they itched furiously as if I’d sustained a bevy of bug bites. It grew worse. My photography mentor, the local pharmacist treated me for the condition. He concocted a formula with camphor and other smelly agents. It was a cream that I spread on my hands. To secure it I had to wear white cotton gloves, even to school, which was embarrassing. The kids said I looked like a bellhop and smelled like a cedar chest.

Time frequently imputes greater value to what once seemed ordinary. Photographs are typical in that regard. The first informal portrait I ever made was of my grandmother. It was in the late forties. She was being treated for cancer and had come to live with us. She had a warmth about her. It was infectious and her presence in the house, although we all knew where it would eventually lead, was a blessing for all of us.

I took her picture one day standing in front of a mirror in the dining room. She was wearing her half-hidden bemused smile the way I always remember her. Considering how inexperienced I was, the photograph was well composed combining soft shadows and muted highlights, graphically portraying the gentleness of her personality. Time increased the portrait’s place in the hearts of the entire family. Her time, then, standing before the mirror was a split second, maybe only one thirtieth of one, just a fleeting moment of one’s life captured as only a photograph can.

Please join Nanny, Charlotte and me on Friday evening, August 3rd at the exhibit and an artists’ reception from 5pm to 7pm at the Trippe Gallery in Easton.

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.