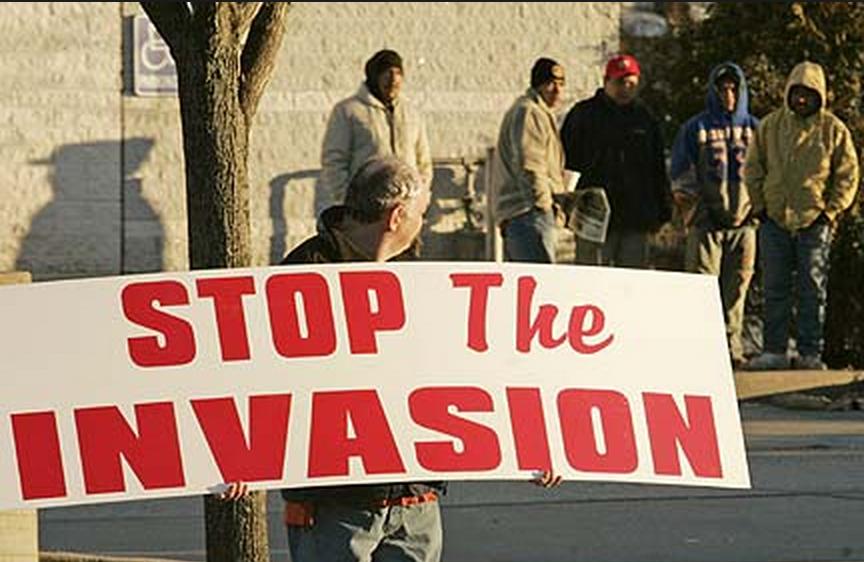

It’s undeniable that when discussing the topic of illegal Latino immigration in the U.S., opinions are often fast and fierce. Compounded by the fact that undocumented Latinos are no longer a small group easy to ignore, once limited to only agricultural regions or towns close to the border, the topic is now relevant to the daily lives of the majority; a tangible shift in terms of “who cares” about the subject. However, the three sides that are perhaps becoming the most important to consider in regards to our communities, schools, and nation are often (still) overlooked: the toddlers, the children, and the young teens.

It can be surprising that the illegal Latino immigrant experience often begins with these three groups, not always the grown men we’ve come to imagine when thinking about who is literally making the trek across the border. Take Isabel, who crossed the border at only five years old, led by a man she had never met and part of a group of strangers.

Or Maria, whose trek across the border at the age of eight took a turn for the worse when one of her traveling companions drowned in the river leading into the US, and the coyote fled, abandoning her in the desert.

Silvia is a young teen who crossed the border with her pregnant mother at thirteen to escape a Mexican town infested with cartel violence. The physical demands of the journey took their toll on everyone, but particularly on Silvia’s mother who lost the baby mid-trek, and on Silvia, who very nearly lost her mother.

The unifying feature of these individuals is how little they were involved in a decision that has affected nearly every aspect of their lives since. Being children, none possessed the knowledge to even begin to predict sociopolitical ramifications of something so humanly basic as wanting to re-join a mother, father, or sibling who was nothing more than a distant memory, if that. Nor did they posses the emotional maturity to knowingly and independently embark on the extremely dangerous and demanding journey across a national border.

What is remarkable about each is how simply American they now are. Upon reuniting with their families each began school in Kent and Queen Anne’s Counties immediately, and by virtue of receiving enormous amounts of support from a very small group of individuals they were able to acquire an English language and Eastern Shore lifestyle fluency that rivals my own. I know this from witnessing it first hand having worked intimately with these women (and many more) for several years.

Their stories are ones of abandonment and struggle, yet also of resolve and nationalization. What if the five year old has since become an elementary school teacher, or that the eight year old earned a scholarship to attend university? What if the thirteen year old was now studying to be a bilingual nurse? Commonly, such outcomes are not only praised for being stories of triumph over adversity, often held up as examples of how the human spirit overcomes struggle, they’re down right facilitated for other immigrant demographic groups.

Unfortunately not one of these endings is possible for these three, or for any of their many, many undocumented peers who find themselves with no future beyond high school. While federal law mandates free and accessible public education for anyone (no questions asked) until 18, no law has yet passed that addresses what an illegal young adult may do after they turn 18 or complete high school. Mind you these are individuals who were raised in American schools, communities; influenced by American culture and expectation just as much as your children, and even you.

So many of these kids don’t even know they carry the loaded label of being an “illegal” until they try to pursue the ambitions that they have been told are possible, because here in the U.S. yes, you can be who you want, yes you can build that dream. Is it fair to so welcomely educate, and more importantly assimilate, this demographic of “Dreamers” who did not knowingly take that first step into a system that promotes promise and access, yet ultimately rejects them?

Our communities are changing, a fact that has long been on the table for discussion yet for equally as long skirted around. Undocumented children, teens, and young adults are here. Once we as a nation fully acknowledge this, would we then be able to discuss the more important matter that for these millions of young people their home, the only home they’ve ever known, is here? Might it lead to finding real solutions that keep families together, and endeavor to eradicate the current state of paranoia, profiling, and trauma, actually leading to progress? While it may be true that “no por mucho madrugar, amanece más temprano”-everything happens in its own time- quite possibly we’re missing that the time for visionary social change is now.

Kaitlin Thomas is a lecturer of Spanish at Washington College

Eric Knox says

Editor,

I could not agree more. Thank you Kaitlin for your thoughtful direct challenge that we must close this American chapter now. I hope your message is acknowledged with action. Thank you. eric knox