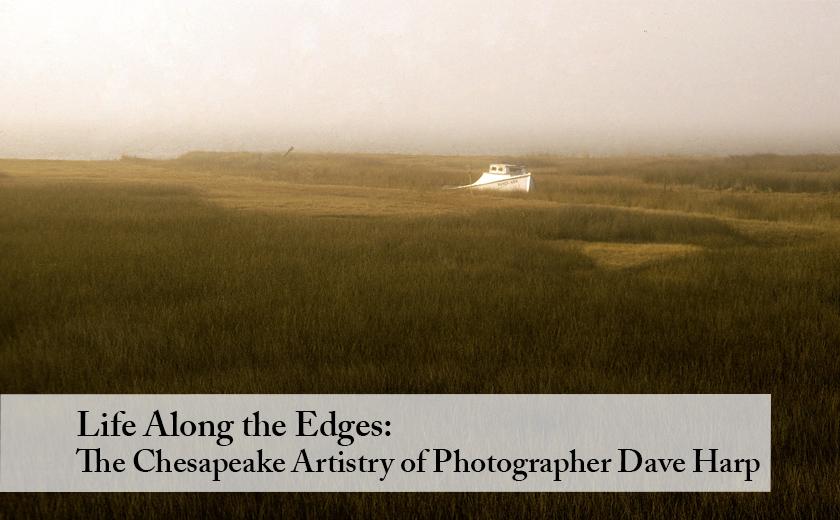

Life Along the Edges: The Chesapeake Artistry of Photographer Dave Harp

The Spy Newspapers may periodically employ the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance the clarity and accuracy of our content.

Nonpartisan and Education-based News for Chestertown

The Spy Newspapers may periodically employ the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance the clarity and accuracy of our content.

View of Chesapeake Bay from the shore of the farm where Frederick Douglass lived in 1834 showing Poplar and Kent Islands in the distance.

Frederick Douglass devoted some of his most famous passages to describing the anguish he felt as he stood on the shores of the Chesapeake during his brutal 16th year of slavery and watched the ships sail by to distant lands of freedom.

“Those beautiful vessels, robed in purest white, so delightful to the eye of freemen,” he wrote, “were to me so many shrouded ghosts, to terrify and torment me with thoughts of my wretched condition.”

A series of press reports over the years, including a fresh outpouring this summer, has sought to rob Douglass of that vision and the particulars of his life in 1834.

Instead of suffering abuse in a field along the shore of the Chesapeake where he could see the Bay’s broad expanse and the ships coursing through it, they have put Douglass on a distant waterway called Broad Creek miles from the Bay on a property later owned by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. These stories blossomed anew after Rumsfeld died in June, when MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow and others lambasted the deceased Pentagon chief at length for having owned the same estate where Douglass suffered his grimmest year of enslavement.

The details of that version of Douglass’s life were simply too good to check. Rumsfeld’s property, said all the reports, was known everywhere as Mt. Misery in honor of the deeds that went on there. That miserable place was owned in 1834 by a brutal slave breaker named Edward Covey. And it was to that estate that Douglass was sent that year by his owner to be broken of his will to resist and be free.

It just so happens that none of that is true.

Here is what is true: In 1834, Frederick Douglass was sent to work for a man named Edward Covey who had leased acreage along the shore of the Chesapeake. While he was at that farm, Douglass was beaten savagely until, in the summer of that year, he rose up and beat Covey back. Two years after Douglass left Covey’s farm, Covey went on to purchase the property that much later came to be called Mt. Misery.

So, just to be clear, Douglass did not spend time at the property now known as Mt. Misery, nor did Covey own that property during the time in question.

These facts are not a matter of actual dispute. If you want to know where Douglass spent his fateful 16th year, just read what Douglass himself wrote of the experience. He devoted a total of seven chapters in his three autobiographies to describing that year in vivid detail.

This willful misreading of the historical record has led many to perpetuate a false story about Talbot County, the place of Douglass’s birth and the location of the most important year of his teens. It has also spawned an avalanche of opinion pieces, a play, multiple news stories and countless meditations on the heartlessness of Rumsfeld to ever have owned such a place. One historian in 2006 opined in the Baltimore Sun that Mt. Misery should be turned into a national monument to mark Douglass’s time there. On the day of Rumsfeld’s death, The Rachel Maddow Show began its evening broadcast with an eight-minute segment on the late defense secretary’s ties to Douglass and Mt. Misery.

We hope with this piece to set the record straight. We hope to give Frederick Douglass the full respect he is due by pushing back against this relentless fiction with the facts of Douglass’s own story, as he told it, all fully supported by the public record.

Douglass was among the greatest of Americans, the fiercest and most determined of abolitionists and among our finest writers, essayists, and orators. The year he spent on a forlorn farm along the shores of the Bay was a turning point in his life, and thus a matter of great importance to the country’s own history.

Getting it right is no less important than maintaining the precise facts of the life of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, or Abraham Lincoln. Getting it right is the least any of us can do to honor the experiences Douglass had on that patch of land, which to this day remains an unmarked and unheralded field dotted with “No Trespassing” signs along the shores of the Chesapeake Bay.

There isn’t the least uncertainty about the route Douglass took to get to the farm where he was sent to spend a year with Covey. Thomas Auld, a shopkeeper and postmaster in St. Michaels, MD, in whose household Douglass had been living, had decided that the only way to tame the headstrong teenager was to lease him to a brutal overseer known for his rough treatment of enslaved workers.

So, on the morning of January 1, 1834, Douglass set off from Auld’s home in St. Michaels to walk seven miles to an area known as Bayside, the district of Talbot County that is alongside the Chesapeake Bay. His destination was a farm on its shores that the 29-year-old Covey, a tenant farmer at the time, leased. All the particulars, all the details, are laid out in Douglass’s own memoirs, or in the many biographies of Douglass.

Douglass writes in My Bondage and My Freedom that he “paced the seven miles, which separated Covey’s house from St. Michaels…” He describes the “little wood-colored house” the Coveys lived in about a mile toward the shore off the main road, and how you could see from that house the Bay “white with foam, raised by the heavy north-west wind.” He described how he could see Poplar Island and Kent Point from where he stood, two landmarks visible along only a portion of that shoreline.

“Covey’s house, small, unpainted, weather beaten, stood near the bay shoreline at the end of a lane,” wrote Dickson Preston in his 1980 book on Douglass’s upbringing, The Young Frederick Douglass: The Maryland Years. “Today, nothing remains of it—even the site has been eaten away by erosion, which has devoured hundreds of yards of shore land.”

Mt. Misery, in contrast, is only a one mile walk from St. Michaels. It does not sit alongside the Chesapeake Bay. It sits on a sheltered cove near the headwaters of Broad Creek. Poplar Island and Kent Point cannot be seen from Mt. Misery nor can any portion of the Chesapeake. Broad Creek flows into the Choptank River, which then flows into the Chesapeake Bay, miles away.

The map below illustrates the locations of the Covey farm and Mt. Misery. While Broad Creek is broad at its entrance, it narrows near its end. We would suggest the skeptical take a boat up Broad Creek, anchor in front of the Mt. Misery house, and read the words of Frederick Douglass. “Our house stood within a few rods of the Chesapeake bay, whose broad bosom was ever white with sails from every quarter of the habitable globe.” Floating in the middle of this narrow slit of water will demonstrate why thinking it could support what Douglass describes as a “moving multitude of ships” is risible.

Let us then try to retrace how this myth got started and then grew over the years into the monster it is now. In reprising all this, we do not seek to settle scores or to add to partisan tensions. There is no doubt that partisanship—in this case, an animosity toward the late Donald Rumsfeld—fueled the Mt. Misery myth and made it, for many, too good to question. In setting the record straight, we hope only to put to rest this misbegotten version of Douglass’s early life.

The first news report to kick off the Mt. Misery/Covey/Douglass/Rumsfeld fiction appears to have run in January 2006 in the Baltimore Sun under the headline A tale of two infamous Maryland slave houses. Written by a New York lawyer, the story quoted amply from Douglass’s first autobiography but never paused to check how Douglass himself described the property.

The story contained sentences like this, which came to typify many of the stories that came after: “I can’t imagine a greater denial of our past than to have a defense secretary sitting in a lounge chair, savoring a drink and enjoying a sunset over the bay and then retiring for the night in a house of horrors built by a man whose occupation was ended only by our great national catastrophe, in which hundreds of thousands of American soldiers died.”

It is hard to know what the writer of this story used as the basis for asserting that Douglass was sent to Mt Misery, but he may have been misled by a shoddy Maryland Historical Trust application that a previous owner of the property submitted sometime in the 1970s. That owner was seeking a historical designation for the house, a request that was turned down by Maryland authorities.

In that application, the property owner said that Edward Covey bought the property in 1804, the year before his birth. The application says that Covey “probably built the brick house that now stands there.”

Neither of those statements is true. Any reporter or researcher who put any time into examining Douglass’s own writings, or the many biographies written about his life, should have spotted that mistake easily.

Land records show that Edward Covey acquired the three parcels now known as Mt. Misery in June 1836, including Harrison’s Security and Harrison’s Partnership, from the Harrison family. Talbot historians are confident that the Harrisons built the house that now stands there. Douglass’s lease to work on Covey’s property terminated in December of 1834.

The New York Times then kept the ball rolling with a story six months later, helping solidify the myth in an otherwise breezy story about recent high-profile Washington figures who were buying weekend places in the area.

Two months after that story ran, a historian, Ian Finseth, took to the Baltimore Sun to make the argument that the historical record, and the memory of Douglass, demanded that the site be preserved as “a public site of contemplation, where the meanings of democracy and despotism are given a human face, and a very American face.”

A playwright, Andrew Saito, went on to capture it all in a play called, yes, Mount Misery, in which Covey, Douglass and Rumsfeld all interact within the confines of the Mt. Misery estate. Saito opens the play with a historical note: “In 1834, Frederick Douglass, at age sixteen, was sent by his owner, Thomas Auld, to the farm Mount Misery to be broken into obedience by farmer Edward Covey. In 2004, Donald and Joyce Rumsfeld purchased Mount Misery for a vacation home.”

When contacted, Saito said he based the facts of the play on newspaper accounts, including the story in the New York Times. He said he was surprised to learn that Douglass had spent his 16th year in a very different place.

Many reports have stated that the property became known as Mt. Misery because of Covey’s conduct there as a brutal slaveowner. But there is no evidence in the historical record that anyone called the house in question by that name until sometime in the 1940s. There is some suggestion that some portion of the land in that area had been called Mt. Misery. At least one historian attributes the designation to a period in the 1600’s when Lord Baltimore deeded various tracts of land in the region and named them after Caribbean landmarks along trade routes. There is a mountain in St. Kitts that went by that name until the early 1960s.

A Talbot County deed filed in 1947 states that the property formerly known as Harrison’s Security, Harrison’s Partnership, and Prouse’s Point shall “now be known as ‘Mt. Misery.’” As far as we can tell, that is when the practice began of calling that particular estate by that name.

The day Rumsfeld died in late June, Maddow launched her nightly show on MSNBC with an incredibly detailed account of Douglass’s year of torment on Covey’s farm. She quoted extensively from Douglass’s own memoirs, and then perpetuated all the same errors that the previous news stories did, each evidently relying on the other. The Rumsfeld property, Maddow said in the segment, is ‘the same actual physical place in which the great Frederick Douglass was tortured and beaten and worked nearly to death every day for a year.”

Rumsfeld, according to Maddow, reveled in his chance to relax at the same place where Douglass had been so mistreated. “He would like to have the Chinook helicopter drop him off at the slave breaker`s home where Douglass was nearly tortured to death. He could relax there.”

Covey recedes from history soon after his star appearance in Douglass’s first memoir, which appeared in 1845, the year before Covey purchased the Mt. Misery property. Douglass describes Covey as “a poor man, a farm renter,” who builds his fortune not just as a slave breaker but also a slave breeder. Census, land records and old maps show that Covey did well for himself. He had nine children and bought prime acreages around Talbot County, including the so-called Mt. Misery property outside St. Michaels that Rumsfeld later acquired.

A news clip from 1867 notes that Covey sold one 300-acre property, out near Claiborne, for “$45,000 in currency.” Another clip from two years later makes this short announcement: “During Christmas week a new tenement house on the property of Edward Covey, in Church Neck, occupied by a colored man, was burned. All the furniture of the occupant was destroyed.” Church Neck is near where the Mt. Misery manor stands.

If at this point you are uncertain what to believe, we suggest that you drive to St. Michaels. Starting from the corner of Talbot and Cherry Streets, where there is a Frederick Douglass marker across the street from where Thomas Auld’s house used to be, drive—or walk, for that matter, as Douglass did that New Years Day of 1834—6.3 miles on Route 33, the only road to Bayside, which Douglass described as “the main road, bending my way toward Covey’s.” The route of that road has changed little over all those decades.

Pull into the New St. John’s United Methodist Church parking lot in Wittman, on the left side of the road. Walk across Route 33 to stand alongside what’s left of the field where Douglass toiled for a year.

If the trees nearer the water’s edge don’t block your view, you should be able to see Poplar Island to your left and the tip of Kent Island to your right. Then read Douglass’s passage for the ages, which includes this anguished plea—“Only think of it; one hundred miles straight north, and I am free!” Ask whether this is the hallowed ground that should be preserved so we can remember it properly.

Neil King Jr. served for 20 years as The Wall Street Journal’s chief diplomatic correspondent, senior politics writer, and global economics editor. He works now as a writer and editor and divides his time between Washington DC and Claiborne, MD.

Jeff McGuiness was the senior partner of a public policy law firm based in Washington, DC, and founder of HR Policy Association. A fine arts major in college who served as a photographer in the Air Force during the Vietnam War Era, he has picked up where he left off 50 years ago with Bay Photographic Works. He lives in St. Michaels, MD.

Their last collaboration for the Spy was earlier this year entitled “Statues and Fields,” which can be viewed here.

The Spy Newspapers may periodically employ the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance the clarity and accuracy of our content.

The Spy Newspapers may periodically employ the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance the clarity and accuracy of our content.