For the better part of three centuries, politicians, entrepreneurs and navigators have viewed the Delmarva as an inconvenient obstacle standing in the way of wealth and progress.

When Bohemian explorer and cartographer Augustine Herman was commissioned by Lord Baltimore to map the region in the 1670s, he quickly discovered that the Eastern Shore rivers reached to within just miles of the Delaware Bay.

A canal could shave days off a sea voyage around the capes and back up into the Chesapeake.

It would be almost 160 years before the first Chesapeake & Delaware Canal opened in 1829. Its success set in motion another century and a half of engineering studies and surveys to find other paths to the Atlantic.

The goal was to provide a more direct sea connection between Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York and a dependable trade route through the Delmarva.

The existing C & D Canal was limited to barges, schooners and bateaus. It had a history of failures. The locks leaked, the banks collapsed. During a storm in 1873, the rain-swollen reservoir that supplied the locks (now Lums Pond State Park) near Summit, Delaware, burst.

A New York Times story on August 22, 1873, reported that the reservoir “emptied its tremendous volume into the fields and the canal, sweeping all before it, carrying away a house, breaking the approaches of the railroad bridge, destroying the abutment and filling the canal at that point with earth and debris. Fourteen boats were swept into the meadows and wrecked. In consequence of this immense volume of water, so suddenly emptied into the canal, breaks are reported at both the Chesapeake and Delaware ends of the canal and it must be close for many days for repairs.”

The report also noted:

“Most of yesterday’s peach-trains moving northward got through before the break occurred but it is believed that 20,000 baskets were caught, all of which are a total loss.”

By the late 1870s, merchants and politicians from Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York were clamoring for a ship canal deep and wide enough to handle ocean-going vessels.

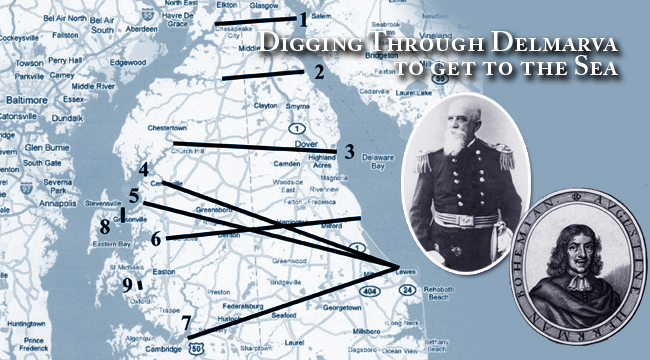

The most comprehensive survey by the Army Corps of Engineers took place in 1878 and 1879. Colonel William Price Craighill, for whom the shipping channel leading to Baltimore is named, headed it up.

Craighill, a West Point graduate and Civil War veteran, led a team of surveyors and engineers that came up with six new routes for the canal, any one of which would have greatly changed the course of Eastern Shore history, as well as shipping traffic.

One of the proposals ran the canal from the head of the Sassafras River straight across Delaware to Liston’s Point on the Delaware Bay. That route was the shortest, but discounted because it was susceptible to freezing the in winter.

Another route started at Southeast Creek off the Chester River between Chestertown and Church Hill and cut through Dover on its way to the Delaware Bay.

Two Queen Anne’s County routes were studied. One started at Queenstown and the other at Centreville on the Corsica River. Both ended at Broadkill Creek, three miles above the Delaware Breakwater at Lewes.

Yet another route entered the Wye River heading east to Skipton Creek then across to Milford, Delaware, and entering the bay at Mispillion Creek.

But the route that Craighill favored most would have had the greatest impact on the Land of Pleasant Living.

The route from Baltimore crossed the Bay to a widened and deepened Kent Narrows then down Eastern Bay to the Miles River. It called for a new canal cut between Oak and Plaindealing Creeks, down the Tred Avon to the Choptank five miles up from Cambridge. The route then cut through farms and forests to the Nanticoke River and up to Broadkill Creek near Lewes.

Colonel Craighill liked that route because his study showed it only froze 10.5 days a year over the previous three decades, compared with 24 days on the northern Chesapeake.

He calculated that a steamship could make the trip from Baltimore to Lewes in 16.5 hours, compared with the 33.5 hours it took by steaming down the Bay and around Cape Charles.

Craighill estimated the cost for the canals would range from $8 million to $41.5 million, with the Sassafras route being the cheapest and the Centreville cut the most expensive. His Choptank proposal was estimated at $18.5 million, including the Oak-Plaindealing Creek canal.

For the next fifteen years, the plans were debated without a shovelful of dirt being turned.

In 1894, President Grover Cleveland appointed Craighill to a board to decide which of the routes would be constructed. A fellow board member was Navy Captain George Dewey, who would go down in history for his remark “You may fire when ready, Gridley,” at the start of the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish-American War.

The board announced in December 1894, that after all of the study, surveying and speculation, the primary route of the existing C & D Canal, starting at Back Creek on the Elk River and cutting through Chesapeake City, would be the path for a new, sea-level canal.

Baltimore officials were upset at the decision. They liked the Choptank route because it was a faster path to Lewes and the Atlantic. The members of the board said their decision was based on sound military judgment. The existing site up the Delaware was easier to defend in case of an enemy attack from the sea. They said an entrance near Lewes would require major fortifications. It didn’t hurt that the already-cut canal was the shortest of the routes or that it would cost $7 million.

Craighill never saw any of his plans for the Delmarva come to completion. He reached the rank of brigadier general and retired in 1897. He died in 1909 at the age of 75.

It wasn’t until 1919 that the federal government bought the privately held C & D Canal and began improvements. Today, the canal is 35 feet deep, 450 feet wide and 14 miles long.

The Oak-Plaindealing Creek canal of Craighill’s Choptank route stayed on the books for decades. And, for a good reason. Ever since the earliest sailors plied the waters of Talbot County there has been talk about slicing a channel from the Miles to the Choptank. It takes the better part of a day to get from St. Michaels Harbor to San Domingo Creek, three blocks by land, 32 miles by water.

The idea of an Oak-Plaindealing Creek canal popped up in federal government reports in 1912 and again in 1935. Politicians and developers from the Eastern Shore worked through the 1930s, 40 and 50s to get support for it from federal and state governments.

At one point in the late 1950s, the Star Democrat reported that the owner of the 700-yard stretch of farmland that separates the creeks offered to give up the rights to his property in exchange for building a 100-slip marina and developing the real estate along the canal for waterfront homes.

Letters to the paper’s editor show a lively debate between those for the canal and those against it.

One writer noted that there was plenty of marshland that could be filled with the dredged soil.

“Real estate values would certainly not suffer. Waterfront acreage along the proposed canal would be created and revitalized from the creation of an all-weather route,” one writer opined.

Another area resident wrote that he had witnessed extensive damage to the environment when a new boat channel was dredged in Barnegat Bay, New Jersey. He warned that fish and waterfowl would be harmed if the canal were cut.

Whispers of the canal blew through again in the early 1970s, but once again, after more studies, committees and reports, the Oak-Plaindealing Creek canal faded away.

One can’t help but wonder what Craighill’s plans would have meant to this part of the Eastern Shore. More than 25,000 vessels travel the C & D Canal every year. Would log canoes have to fight for room at the mark with containerized cargo ships? Would weekend cruisers have to contend with tankers rounding the Choptank River Light?

Would there be a Red-eye Dock Bar in Royal Oak?

This story first appeared in the Tidewater Times.