“Covid really brought it up again,” says Master Gardener Eileen Clements.

“Covid really brought it up again,” says Master Gardener Eileen Clements.

A way to feed yourself – and maybe share extra lettuce, a few Gadzukes squash, Cherokee Purple tomatoes or Aji Limon hot peppers with your neighbors or friends. Victory Gardens – or their current iteration – can offer a sense of control in a time of uncertainty.

“A garden is a place of hope,” Clements says.

She’s right. Even more, a garden can offer help for that most basic of needs: Food. Covid lockdown increased the number of gardeners exponentially. Suddenly food production, distribution and availability weren’t taken for granted. Seed companies sold out, garden centers were besieged, and even apartment dwellers had a pot of lettuce or herbs sitting on a balcony or sunny windowsill. We didn’t call them victory gardens, but the small sense of triumph they offered in a world that had gone pear-shaped was therapeutic.

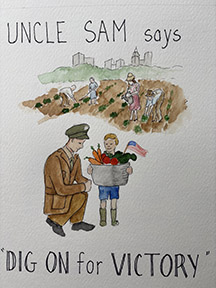

Victory Gardens have a long history. Introduced to the American public in 1917 when we entered WWI, they were a way for civilians to help win the war by growing food for the troops.

A startling percentage of recruits were rejected due to malnutrition, and the adage: An army marches on its stomach is not apocryphal. Destruction of food production and subsequent starvation have long been tactics of war.

“Farms were getting battered and blown up, and we cared enough to send food and help our allies,” Clements notes.

During the Depression, they were termed ‘thrift gardens’ without the patriotic overtones, but with WWII came rationing, and Victory Gardens were once again a way to supplement both military and civilian. Vegetable gardens sprouted up on every available piece of soil. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt planted a Victory Garden on the White House lawn in 1943.

“Victory Gardens became a source of civic pride and a way to show patriotism,” says Clements.

“I understand where the name ‘victory garden’ comes from,” says Master Gardener Shane Brill. “And I appreciate the tradition of people uniting against a common adversary.” But he says it might be time to rename them. “Maybe Resilience Garden,” he says. “Gardens can be a source of empowerment and resilience in local communities.”

Former First Lady Michelle Obama planted a vegetable garden at the White House to encourage better nutrition, especially among children. Post-White House, the Obamas are building The Eleanor Roosevelt Fruit and Vegetable Garden at the Obama Presidential Center.

Though the White House was a special case, gardens – especially community gardens in pockets that would otherwise lie derelict – are almost sacrosanct to many. During the 1992 Rodney King riots, South Central Los Angeles was sacked, but the community gardens there were left untouched. Closer to home, Baltimore’s tucked-away community gardens in edgy neighborhoods are also places of special protection. A kind of victory over discouragement and frustration.

Part of the victory is simply encouraging people to reconnect with the “primal-ness” of gardening. “I do a lot of work in nutrition,” says Brill, director of Washington College’s campus garden who teaches courses in culinary wellness, fermentation, and ecological design. “Sunlight and movement are such powerful levers for our wellbeing. I think food is our most intimate connection to the natural world, and the garden is our gateway to that.”

“There’s something about knowing what it takes to produce food,” adds Master Gardener Barbara Flook. Flook, whose parents had a big vegetable garden, planted her own as soon as she had her first house. “Also, when you grow your own food, you think wasting it is a sin.”

Like Flook, Master Gardener Sara Bedwell was the child of farmers and gardeners, but got into growing food more seriously as a paid intern at Wye Manor’s gardens in 2014. She then went on to work as the vegetable gardener at Camp Pecometh’s 2-acre chef’s garden.

“When I left Wye Manor, the horticulturist there gave me The New Vegetable Grower’s Handbook by Frank Tozer,” she remembers. “It’s the one book I’ve kept, and it’s got my little notes in it.“

Always hungry for more knowledge, Bedwell had wanted the education the Master Gardener program offers but couldn’t coordinate the course timing with her work schedule – until Covid when the course went all-online. She saw her opportunity.

“I had wanted to expand my knowledge, and I like volunteering,” she says. “For me, it was being able to learn new things and then be able to spread that knowledge to the community.”

Bedwell, who works two jobs, is also in the process of clearing two acres in large part to grow food Meanwhile, she grows in buckets ‘cause she’s gotta eat.

“I can be picky,” she says. “Lettuce from the store doesn’t taste as good as what I grow.” “I do not like store-bought tomatoes at all, but if I grow them, I like them.”

Picking your own basil, tomatoes, squash, and more is also both economical and satisfying. Once Bedwell has the plantable acreage she anticipates, there will be plenty to eat, preserve, and share with friends, neighbors and perhaps the local Food Bank.

“The whole idea of a victory garden, even if you’re growing something for yourself and have too much, you pass it on,” Clements notes.

Whatever we call it – victory, thrift, community, or resilience – a garden embodies hope.

Artist: Eileen Clements

PAR -Plant a Row for the hungry

https://community.gardencomm.org/c/about-par/

Resources:

Boswell, Victor R. (1943) Victory Gardens. USDA Miscellaneous Publication No. 483.

Collection of the National Agricultural Library.

“Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front.” National Park Service. www.nps.gov

“Victory Garden at the National Museum of American History.” Smithsonian Institute. www.gardens.si.edu

johnson fortenbaugh says

Bravo, Nance!

You said eloquently what we all feel.

Let’s Grow!

Jenifer says

❤️

Celeste Conn says

A timely reminder Nancy.

I’m poised to start mine!

Jenifer says

❤️