As a newly-fledged adult, I entertained the idea of becoming a greeting card writer, going so far as to look up what was required to apply for that kind of position. It wasn’t that I had a deep-seated desire to take on a nameless, faceless writing job. Rather, I thought that even with no experience, I could crank out less anemic verse than what I found on the cards available at local stores.

More recently, I’ve had similar thoughts about fortune cookies. What has happened? Have you noticed it, too? Most don’t offer fortunes at all. Instead, they’re stuffed with aphorisms or statements, and on occasion, quotes lifted from famous people, without any credit given.

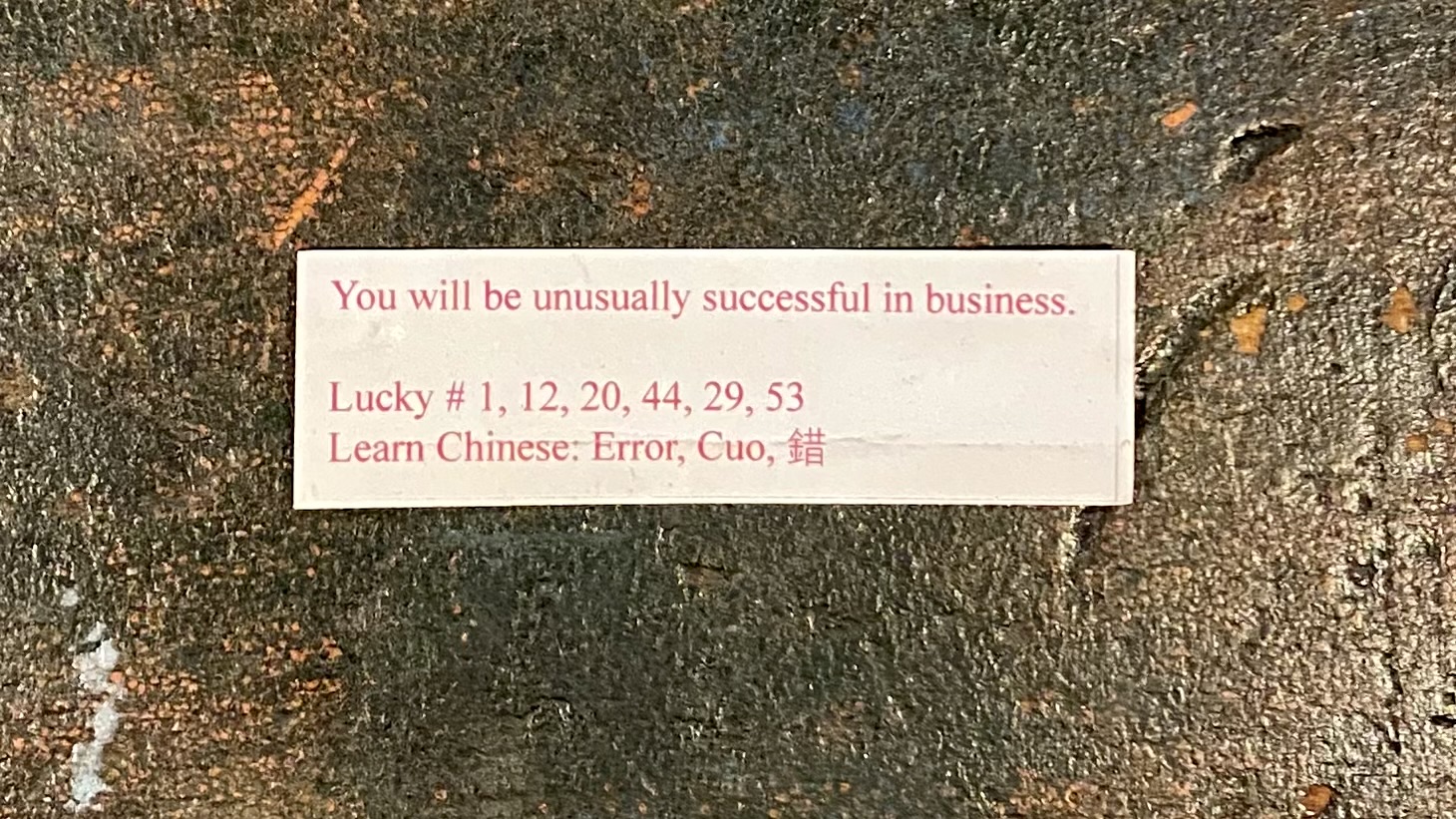

The good ones are rare enough that I am apt to save them. I currently have four, and that speaks volumes. Granted, we don’t eat Chinese food that often. But when we do, I don’t think it’s asking too much to want my fortunes to be telling. The other stuff is just fluff. I don’t play the lottery, so the lucky numbers aren’t useful for me, and thus far, I’ve not managed to learn a word of Chinese.

This is not a fortune. This is a quote from comedian, Steven Wright.

I figured I wasn’t the first red-blooded American to lodge such a complaint, so I decided to explore cyberspace in search of ideas for when, and why, the downfall began. Shoddy craftsmanship often has roots in cost-saving measures, also known as corner-cutting, and I can’t be sure there’s not a little of that happening here. But the story that revealed itself indicates otherwise, and it is a good deal more intriguing than I would have ever predicted.

First, because it relates to where we’re going, I want to bring you the history of the cookies themselves. Despite their ubiquity as a traditional treat at the conclusion of a Chinese meal, these folded, foamy, vaguely vanilla crescents probably did not originate in China, at least not in the way we might think.

Were you to walk the path this cookie traveled to get to the version we know today, you’d first bump into a bunch of 14th century Han Chinese hiding revolutionary messages inside—or under, or on top of—mooncakes, a seasonal confection enjoyed at the Mid-Autumn Festival which celebrates the fall full moon and harvest. The story goes that the oppressed Han, galvanized by the secret notes in their celebratory cakes, rose up to overthrow the Mongolian Yuan Dynasty, which had occupied China for nearly a century.

But Hok-Lam Chan (or Chan Hok-Lam, in customary Chinese), a Hong Kong born historian, determined that those tales are pure fiction, probably retold without revision from a place of nationalistic pride.

True or false, using baked goods to convey messages does not, to me, constitute a credible origin story for our friend the fortune cookie. Humans have devised all manner of disguises for their missives, including scalps, smoke, and dead animals, so it’s not as though the mooncake caper was a particularly novel approach.

Now, our explorations jump ahead to the 19th century. While the details grow a little less fantastic, they’re still not much clearer. At this point, the Chinese continue efforts to link themselves to the provenance of the cookie, and except for the fact that the dessert is essentially nowhere to be found in China, they might have succeeded.

The trail on this part of the journey takes us to David Jung, a Chinese immigrant living in Los Angeles in 1918. Jung owned the Hong Kong Noodle Company and, purportedly, gave cookies with bits of scripture inside to the unemployed. But the path also forks over to Seichi Kito, a Japanese-American, also in L.A., who founded Fugetsu-Do, a bakery that still exists today. Kito, we discover, sold haiku-stuffed cookies to Chinese restaurants. A snack company called Umeya also gets in on the act of claiming the title as inventor.

Meanwhile, over in late 1800s San Francisco, it’s said that Makoto Hagiwara, a gardener whose life’s work was maintaining the well-known Japanese Tea Garden, gave out a modified version of an even older style of Japanese wafer, to express thanks to those whose protests helped him get his job back, after he was fired by a racist mayor. The cookies he shared came from Benkyodo Bakery, which not only alleges to have developed the cookie’s flavor as we know it, but also to have invented a machine to produce them in large numbers.

All this, and nothing of the little slips of paper inside! Join me for one more jaunt before we find our way back to the fortunes themselves.

The older Japanese cookie mentioned above? That one traces back to 1870s Kyoto. Journalist Jennifer 8. Lee, in her book about the history of the fortune cookie, explains how local bakers, back then, made crackers called tsujiura senbei (translation: fortune cracker) with a shape identical to the one we enjoy today. She also sites research from Yasuko Nakamachi, who discovered references to the crackers, and even an illustration of them being made, in historical literature written well before the modern cookie appeared in America.

Tsujiura senbei – photo from: Atlas Obscura

By the 1950s, through twists of fate that include World War II, the American palate, traveling military personnel, savvy food-business owners, and the tragedy of Japanese internments, the U.S. version of the fortune cookie had taken the Chinese-American food scene by storm.

Some manufacturers, like Wonton Foods, based in Brooklyn, NY, still keep a fortune-writer on staff. Donald Lau held the position for thirty years and described it as one of the hardest jobs he’s ever had. He handed over the reins about eight years ago, citing writer’s block as his reason for stepping down.

“At his peak, Lau wrote maybe 400 fortunes a month. But the work drained him. He couldn’t meet America’s constant demand for good news.” – The Week

His job is now held by James Wong, whose uncle founded Wonton Foods in the early 70s. The company also maintains a database of around 15,000 fortunes and uses a third that many in the cookies it produces everyday.Outside of Wonton Foods, there were once just two other fortune-making companies in the country, one run by Steven Yang, the other by Yong Sik Lee. But, that was later—after the two men stopped talking to each other, and Yang stopped working for Lee, and instead became his competition. When he left to start his own business, Yang took Lee’s fortunes with him, literally and figuratively. He stole a stockpile of Lee’s messages and eventually beat him in business, too.

Lee, now in his 80s, is no longer working, but Yang and his staff of five are still cranking out tiny bits of wisdom, using nontoxic materials, just in case someone eats one. Over the years, fortune databases have grown as writers continue to refresh repositories with new messages. Of the three billion cookies manufactured each year, most are consumed here in the U.S. Keeping customers happy, it seems, is a bigger challenge than might meet the eye. I don’t have to tell you how readily Americans take offense or will decide they can do a better job than a trained professional.

Yes, my hubris has taken a nosedive. Now that I know more of what’s involved, I can’t imagine coming up with fortunes enough to satisfy even half the country’s cookie demand. A week on the job and I’d be hitting dusty anthologies of wise sayings and watching reruns of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood for creative inspiration.

My reality check is probably for the best. Recent news reports are upsetting. All too soon, it seems, the Steven Wongs of the world will be replaced by artificial intelligence. Staffers and freelancers, the likes of whom have created pithy cookie content for generations, will be relegated to churning out prompts for ChatGPT so that computers can tell us what our futures have in store.

Something tells me I’m going to like those predictions even less than the ones I get now. Maybe I need to start my own fortune cookie company instead.

Elizabeth Beggins is a communications and outreach specialist focused on regional agriculture. She is a former farmer, recovering sailor, and committed over-thinker who appreciates opportunities to kindle conversation and invite connection. On “Chicken Scratch,” a reader-supported digital publication hosted by Substack, she writes non-fiction essays rooted in optimism. To receive her weekly posts and support her work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber here.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.