Edmonia Lewis (1843-1909) was one of the American women sculptors who in the 1860’s went to Rome, where the Carrara marble quarries were located, and made names for themselves in the world of art. Much of Lewis’s biographical information is verifiable, but she had a vivid imagination and tended to exaggerate. She was born either in Ohio or Albany, New York. She was Ojibwe/Chippawa and Haitian. Her Indian name was Wildfire; her brother’s name was Sunrise. Orphaned at five, she lived with the tribe until she was twelve. She spoke of her parents: “My mother was a wild Indian and was born in Albany, of copper color and straight black hair. There she made and sold moccasins. My father, who was a Negro and a gentleman’s servant, saw her and married her…Mother often left home and wandered with her people, whose habits she could not forget, and thus we, her children, were brought up in the same wild manner. Until I was 12, I led this wandering life, fishing, swimming…making moccasins.”

In 1856, Lewis received an Abolitionist Scholarship to Oberlin Academy Preparatory School in Ohio. Wildfire (Lewis) entered Oberlin College as Mary Edmonia Lewis. Oberlin College was the first American college open to women and people of color. She studied languages, arithmetic, composition, public speaking, and drawing. She was the victim of racism every day. In her final year (1862), she was accused of poisoning her two best friends, tried, defended by John Mercer Langston, and acquitted. A physical attack that left her for dead, along with more accusations of wrong-doing took their toll. She left Oberlin without registering for her final semester.

One of her Abolitionist supporters, Frederick Douglas, advised her to go East. In New York she met abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet. He put her in touch with the William Lloyd Garrison in Boston (1864), who introduced her to portrait sculptor Edward Brackett, with whom she began training in sculpture.

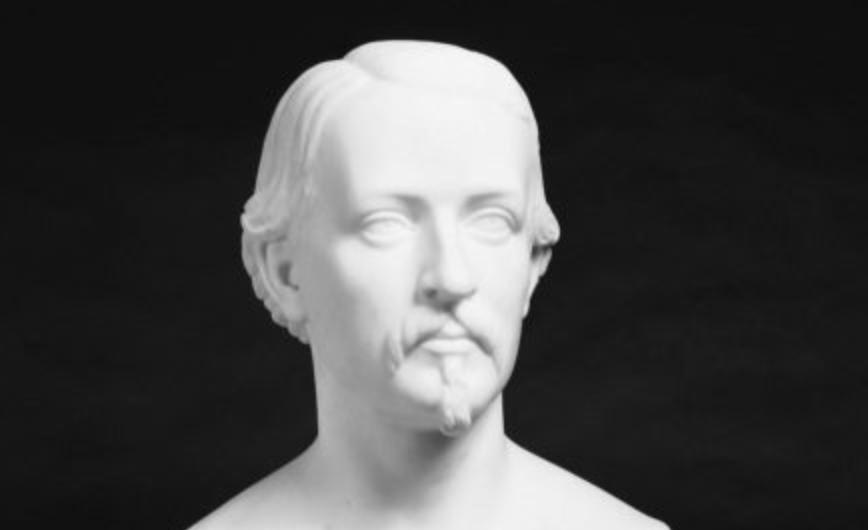

In 1864, she opened a studio in Boston. Her first portrait sculpture was “Colonel Robert Gould Shaw” (1864) (23.5’’ x 13’’ x11.5’’). Shaw, a Bostonian, led the 54th Massachusetts regiment, the first black regiment in the Civil War. He was killed with his troops when they attacked Fort Wagner in South Carolina. On the base of the portrait bust Lewis carved the words “Martyr for Freedom.” He was extremely popular in Boston. Lewis made 100 copies of the Shaw statue and sold each for $15. She also sculpted medallions of John Brown, William Lloyd Garrison, and prominent Boston abolitionists. When the Civil War ended in April 1865, Lewis used her earnings from the Shaw sculpture to travel to Italy.

The Emancipation Proclamation was declared in 1863. The Civil War ended in April 1865, and the Thirteenth Amendment that banned slavery throughout the United States was ratified on December 1865. Never-the-less, in an 1878 interview with the New York Times Lewis stated, “I was practically driven to Rome in order to obtain the opportunities for art culture, and to find a social atmosphere where I was not constantly reminded of my color. The land of liberty had no room for a colored sculptor.”’

When Lewis arrived in Rome in 1865, she was welcomed into the group of expatriates that included Mark Twain, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William Lloyd Garrison, Charlotte Cushman, and Harriet Hosmer. The prominent sculptor Hiram Powers let her share his studio in Rome until she found one of her own.

Her first non-portrait sculpture was titled “Freedwoman and Child” (1866). Her next work “Forever Free” (1867) (3.5 feet) became one of her most popular works. The work originally was titled “Morning of Liberty”; however, Lewis changed the title to “Forever Free,” found in the text of the Emancipation Proclamation. A young, partially clothed man raises his left arm, displaying a broken chain and a shackle. Under his foot is the ball of the chain. His right-hand rests gently on the shoulder of a young women who kneels beside him, her hands clasped and raised in a thankful prayer for freedom. Lewis depicted the young woman fully clothed to counteract the idea that African-American women were sexual symbols. “Forever Free” was shipped to Samuel Swell, an abolitionist in Boston.

“Hagar” (1868) (52.5’’) depicts another of Lewis’s themes. “I have a strong sympathy for all women who have struggled and suffered.” In an Old Testament story, Hagar was handmaid to Abraham’s wife Sarah. Since Sarah seemed unable to bear children, Abraham slept with Hagar, as was the custom. She bore him a son, Ismael. Years later, Sarah gave birth to Isaac. Hagar and Ismael were forced to leave and to find their own way. Lewis depicted Hagar as a beautiful woman, but one who prays for help in the desperate circumstances forced upon her. Barefoot, hands folded in prayer, Hagar walks slowly forward into her new life. An overturned water pitcher at her feet is a symbol of her loss. Art historians have interpreted Lewis’s intention to show Hagar’s situation as similar to African mothers in America, abused and left alone by white men.

Lewis’s Indian heritage also played a large part in her choice of subjects. She had read Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha” (1855) about the Ojibwe Indian leader, who finally wins the hand of his true love Minnehaha, a member of a rival tribe. In 1867, Lewis began sculpting individual portrait busts: “Hiawatha” (1867), “Minnehaha” (1867), and “The Old Indian Arrow-maker and His Daughter” (1866-72). In “The Marriage of Hiawatha” (1871) (32”), the two figures look adoringly at each other and hold hands. At the time, the clothing of her Indian figures was considered to be authentic. Lewis tended to blur facial features of her sculptures, except portraits, keeping black, white, and Indian figures indistinguishable. Longfellow visited her studio in 1869 and posed for a portrait.

Lewis returned several times to America, where her reputation as a sculptor continued to grow. The Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876 featured several sculptures by women artists. Lewis’s “Death of Cleopatra” (1876) (3,015 pounds) was a standout and took an unexpected approach for the contemporary audience. Artistic depictions of Cleopatra, a very popular subject at the time, were of her in life. Lewis depicted her in death. Sitting on her throne, regally dressed with richly carved drapery, jewelry, and wearing her crown, Cleopatra holds in her right hand the snake that has just bitten her. Her left-hand hangs limply at her side as it would in death. She is at peace. A touching addition, the heads of her two children with Mark Anthony are carved on the arms of the chair.

The Centennial Exposition included over 500 pieces of sculpture, 151 of them by Americans. “Cleopatra” was a sensation. The People’s Advocate (Alexandria, Virginia) wrote, “The Death of Cleopatra excites more admiration and gathers larger crowds around it than any other work of art in the vast collection of Memorial Hall.” J.S. Ingraham wrote that “Cleopatra” was “the most remarkable piece of sculpture in the American section of the Exposition.”

During her long career, Lewis made portrait busts and medallions of many of the abolitionists. In 1877, Ulysses S. Grant commissioned his portrait, and was well pleased. She presented a bust of John Brown to Henry Highland Garnet in 1878. Her bust of Charles Sumner was exhibited at the 1895 Atlanta Exposition. She was baptized as a Roman Catholic in 1868, and over the years she created several commissioned religious works. In 1883, she prepared a bas-relief altarpiece of the Adoration of the Magi for the Protestant Episcopal Church of St. Mary the Virgin in Baltimore. Her work was exhibited in Paris, London, Boston, Baltimore, Chicago, and San Francisco. She died at the age of 42 in London and is buried there.

Her Roman colleagues described her: “Edmonia Lewis is below the medium height, her complexion and features betray her African origins; her hair more of an Indian type, black, straight and abundant. She wears a red cap in her studio, which is very picturesque and effective; her face is a bright, intelligent and an expressive one. She has the proud spirit of her Indian ancestors; and if she has more of the African in her personal appearance, she has more of the Indian in her character. She is one of the most interesting of our American women artists here, and we are glad to know that she is fast winning fame and fortune.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Marianne Sade says

Thanks, Beverly! Great to see her work shared and to learn more about her fascinating life. If anyone wants to see one of her pieces in person, they can take a trip to the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. They have her “Bust of Dr. Dio Lewis.” For more information and to see a photograph taken of her in Rome check their website: thewalters.org.