“Now after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, behold, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem, saying, ‘Where is He who has been born King of the Jews? For we have seen his star in the East, and have come to worship Him’…And when they had opened their treasures, they presented gifts to Him: gold, frankincense, and myrrh.” (Matthew 2: 1-12) (New King James Version)

The feast of Epiphany is celebrated on January 6, twelve days after Christmas. Matthew describes the visitors as wise men from the east. The number of Magi was determined by the three gifts. At that time, Magi were thought to be astrologers and dream interpreters.

“Adoration of the Magi” (sarcophagus of Crispina) (3rd Century)

The first known depiction of the “Adoration of the Magi” is found on the sarcophagus of Crispina in the Catacomb of Priscilla (3rd Century) (Rome). From the earliest representation, it is typical to see the newborn Baby sitting upright, acknowledging the Magi and accepting their gifts. As they were from the east, they are wearing Phrygian caps (Persia, now Iran), short tunics over trousers, and shoes. They are the same age, and because of the artist’s limited skill, they have the same face. The gifts are not quite identifiable. The first of the Magi offers what is either a vessel or a crown, the second a bowl of fruit, and the third a bowl containing leaves. Behind the Magi are two camels, and at the right is a column with a palm tree-like top. Other sculptures on the sarcophagus depict scenes from the Old and New Testaments.

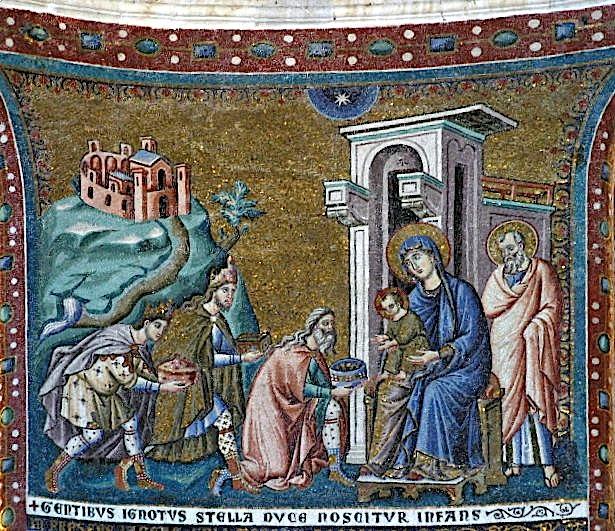

“Adoration of the Magi” (1296-1300)

Several Christian churches were built in the city of Rome in the 12th Century. The Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere, built by Pope Innocent II (1130-1143), was the largest and most important. The Italian painter and mosaicist Pietro Cavallini (1259-1330) was commissioned to decorate the nave with a series of mosaics depicting scenes from the birth to the death of the Virgin. In “The Adoration of the Magi” (1296-1300) the Virgin and Child are seated under a classical white marble arch. Mary sits on a golden bench with a cushion. She wears the traditional blue robe, but she wears red shoes. Only royalty was allowed to wear red shoes. Wearing sandals, the elderly Joseph stands quietly behind her. Dressed in green, the color of renewal and regeneration, Jesus reaches out the accept the gifts.

By the Sixth Century, the Magi had been given names chosen from a list of Middle Eastern rulers. Each Magi represented one of the three ages of man. The gifts were of the quality given to a king, and the Magi were at that time thought to be kings. The oldest of the Magi, Melchior, kneels and offers gold. The middle-aged Balthasar, wearing a crown, offers frankincense. Gaspar, the youngest, brings myrrh. All wear Phrygian/Persian boots, leggings and rich garments.

The sky is gold to represent heaven, in the traditional style of Byzantine art. A path on the green hill leads to a Romanesque church, signifying the journey of the kings to Bethlehem. The Star of Bethlehem appears in a blue circle. The prophesy of Balaam, a descendant of Abraham, can be found in Numbers 24:17: “I see him, but not now; I behold him, but not near. A star will come out of Jacob; A scepter will rise out of Israel.” The Magi (priests of the ancient Persian religion of Zoroaster) were watching and waiting for the Star.

Different from the four-pointed star in Early Christian art, the eight-pointed star depicted here is called the Star of Redemption. The inscription across the bottom of the mosaic states, “With the star as guide, the unknown child becomes known to the Gentiles.” The eight-pointed star also is an ancient symbol of beginnings, resurrection, salvation and abundance in Hinduism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Islam, and Native Americans symbols.

“Adoration of the Magi” (1330-35)

The illuminated manuscript page by the Willenhalm Master contains the “Adoration of the Magi” (1330-35) within the letter a. Mary, crowned as a queen, sits on a chair carved with Gothic pointed arches and rosettes. The eldest King offer Jesus gold, which He accepts and passes to Mary. Gold was a gift the Holy Family could use in their sojourn in Egypt. The middle-aged and young Kings stand behind an altar rail as if they were in a church. The middle-aged king’s gift is frankincense that would help dissipate the odor of the stable. The young king’s gift is myrrh, a consecrated incense used for anointing priests and kings. The middle-aged King points to the seven-pointed star, symbol of the seven days of creation. The star also was thought to ward off evil.

“Adoration of the Magi” (1475-76)

Botticelli, one of the most popular artists in Florence, was commissioned to paint at least seven Adorations of the Magi. This “Adoration of the Magi” (1475-76) (44’’x 53’’) was commissioned by Gaspare del Lama for his chapel in the Church of Santa Maria Novella. Del Lama was a money lender and had difficulty with the law. This painting, like many others commissioned by wealthy Florentines, was to help mitigate his sins in the Last Judgement. Botticelli includes his self-portrait, the first figure at the right dressed in gold. Farther back, an elderly face, thought to be del Lama’s, looks out at the viewer.

Del Lama also paid homage to the influential Medici family. Florence held religious celebrations with elaborate processions through the streets. One of the most prestigious was for Epiphany in which the Medici family often played the Magi. Botticelli includes the Medici and many of their friends and associates. The patriarch of the family, Cosimo de Medici, kneels before the Virgin and Child and reaches out to touch Jesus’ extended foot. He uses a delicate white cloth because he is touching someone holy. Cosimo’s son Piero I (the Gouty), the middle-aged Magi wearing the red mantle with the ermine stole, kneels in the center of the composition. The angel in white and gold is Piero’s son Giovanni de Medici, later Pope Leo X. He holds Piero’s gift, and they exchange glances. Lorenzo de Medici (the Magnificent), also Piero’s son, looks on from the right. Although he stands behind his father and brother, his dark hair and black mantle with red slashed sleeves set him apart.

Easily noticed at the far left is Giuliano de Medici, Cosimo’s second son. He wears a short red tunic, but is noticeable for his strutting pose. He was the “golden boy” of Florence. His favorite horse nudges him. Leaning on Giovanni’s left shoulder is Francesco de Pazzi. Although he looks like he is Giuliano’s best friend, he will assassinate him in the Pazzi revolt against the Medici in 1478.

Botticelli sets Joseph, Mary, and Jesus above the gathering on an outcropping of rocks. The stable consists of a partial stone wall, a large rock, and a makeshift wooden roof. The Star of Bethlehem shines down with golden rays on the Holy Family. Young vines sprout from the crumbling walls. In the distance at the left, Botticelli has painted decaying Roman arches: The old gives way to the new.

Perched high on the stone wall at the right is a peacock. In Christian art, the peacock was a symbol of Christ’s resurrection. The peacock’s splendid plumage is a symbol of royalty. It was thought that when a peacock dies, the flesh does not decay; thus, the peacock became a symbol for everlasting life.

“Adoration of the Magi” (1478-82)

Although Botticelli’s painting of 1475-76, was highly political and was made for public display in the chapel of a church, not all of Botticelli’s Adorations were political. The “Adoration of the Magi” (1478-82) (28’’ x 41’’) (National Gallery, Washington, DC) is solemn and religious. The event takes place in a peaceful, green landscape. The Holy Family and two of the Kings are at the center of the painting in a triangular composition. They kneel to offer their gifts. The middle-aged King is located at the left of center. His righthand rests on his chin as he contemplates the scene. He extends his left arm to present his gift. Joseph leans on his crutch. The ox and the ass look on.

Gathered in a circle in front of the manger, those who accompanied the Magi look on in reverence. Closer to the manger, some individual faces can be seen, but they do not distract attention from the scene. Botticelli includes horses, camels, and the Magi’s attendants at both sides of the painting. The arrangement of the retinue of the Magi, similar to that found in da Vinci’s unfinished “Adoration of the Magi” of 1481-82, is a tribute da Vinci. Botticelli also includes ruins of Roman arches on the left, similar to those seen in his earlier painting and in the da Vinci version. Dead branches protrude from the ruins, while at the right, two tall green trees can be seen. The manger clearly is intended to represent the new replacing the old. Botticelli splits the Roman temple into two parts, which support a new solid wooden roof.

detail of “Adoration of the Magi” (National Gallery of Art)

Botticelli was able to satisfy a number of important patrons and their different spiritual needs. This work probably was painted while Botticelli was in Rome working on the walls of the Sistine Chapel. Here, the beauty of Botticelli’s style is on full display. The colors throughout are delicate and fresh. The figures are placed in graceful poses, and delicate threads of gold extend throughout the entire scene.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Alice M.Barron says

THANK YOU!!