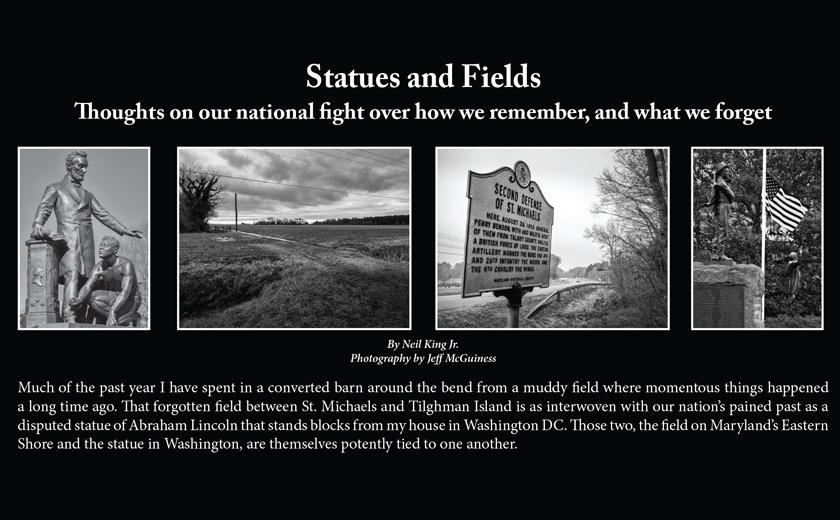

Thoughts on our national fight over how we remember,

and what we forget

By Neil King Jr.

Photography by Jeff McGuiness

Much of the past year I have spent in a converted barn around the bend from a muddy field where momentous things happened a long time ago. That forgotten field between St. Michaels and Tilghman Island is as interwoven with our nation’s pained past as a disputed statue of Abraham Lincoln that stands blocks from my house in Washington DC. Those two, the field on Maryland’s Eastern Shore and the statue in Washington, are themselves potently tied to one another.

The statue—of a benevolent Lincoln holding his hand above a kneeling enslaved Black man that he has just freed—attempts to capture in bronze a pivotal moment in our history. The patch of ground—where a 16-year-old Frederick Douglass famously beat down his white overseer—remains just that: A long rectangle of soggy corn stalks girded on one side by telephone wires and on the other by the eroding shoreline of the Chesapeake Bay.

Douglass was sent to this field to be broken, and he broke the man hired to break him. He had a brawl in this field, enslaved vs. enslaver, that remains an emblematic moment in American history. One historian calls it “the most celebrated fight between a master and a slave in all of antislavery literature.” The path to freedom for the most famous former slave in America began in this field.

No marker or pullout spot along the highway serves to commemorate any of this. A large bullet-ridden sign five miles to the south says, “This Highway Dedicated to Frederick Douglass.” That’s the sole glancing mention between there and St. Michaels, seven miles the other way, to attest to the three years in his late teens that Douglass worked and agonized in bondage while plotting his escape along these twelve miles of road.

Surely Talbot County’s most famous native and among the greatest of all Americans, Douglass devoted a total of seven chapters in his three autobiographies to the single year he spent on this farm. When I read those chapters in the early fall, I was astonished to realize that my Covid refuge had placed me among a hidden drama. I set out to find the place where the famous fight happened. For weeks I picked through Douglass’s writings and consulted old maps and resources online. When I found the field, I was struck by the land’s utter drabness. Old battlefields often have an aura, even a beauty, about them. This was just a patch of overturned earth.

I kept coming back, week after week, to think not just about Douglass but also about when and how—and what—we Americans choose to remember. I wanted to know if any remnants of that year still exist on the ground or in the minds of those living nearby. What I found were a few reservoirs of remembrance against a broader sea of amnesia. It all made me wonder if we shouldn’t erect some small bulwark to human forgetfulness: a cairn, a stone, a plaque that would speak to those whizzing by in their cars and trucks.

Maybe just something that says, “Frederick Douglass Fought Back Here.”

The view across the road from the Methodist church parking lot is of seventy acres of plowed land bracketed by tall pines. A two-track lane cuts from the highway to a tangle of woods. And beyond that, a grey slice of the Chesapeake, creased by morning waves.

I slip down the rutted lane and into the grove of woods. Hidden there are the ruins of a brick house once covered in plaster but now half devoured among vines and trees. I continue past a small pond and an empty barn, and head to the shoreline. Douglass described how he stood on this embankment and marveled at the full-sailed ships and how they spoke to him of a distant freedom. The bay’s “broad bosom was ever white with sails from every quarter of the habitable globe,” he wrote in one of his most famous flights of prose.

He arrived on this property on a New Year’s Day, 1834, “with my little bundle of clothing on the end of a stick,” and left a year later, a changed man, walking back the way he came.

Douglass’s owner sent him here to work for a year under a brutal tenant farmer named Edward Napoleon Covey—“a cold, distant, morose” man, as Douglass described him 11 years later.

Douglass thrived on memory, so his books are uncanny in their vividness and accuracy. He describes exactly how far he walked—seven miles—from St. Michaels to the Covey property. How the road bent in getting there. How you could see from its shore Kent Point and Poplar Island, exactly as I can now. The “wood-colored” house, the names of all its occupants, the names even of the oxen, Buck and Darby. On every page his descriptions stay fresh no matter their years. Of his walk to the Covey farm he says, “There was neither joy in my heart nor elasticity in my frame as I started for the tyrant’s home.”

Covey then was a stocky 28-year-old, freshly married with an infant son, and just getting started. His trade, aside from farming, was to break unruly young black men sent to him at a discount rate to work under his constant eye and frequent lash.

Covey beat him the first week, and from then on at least weekly for any infraction. Douglass had never been a fieldhand, so the work in all weather, from sunrise to well past sundown, sapped his vitality. “The cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died,” he wrote.

On a sweltering Monday morning in August, Douglass decided he would take no more. He had run away three days earlier, and Covey was set to punish him. Their fight reads like a scene from great mythology, as though two embodiments of America were caught in a death struggle.

Douglass was in the hayloft throwing feed to the horses when Covey entered with a rope and tried to bind his legs. Douglass fell to the ground and “Covey seemed now to think he had me, and could do what he pleased.” Douglass resolved then to resist. “I seized Covey hard by the throat, and as I did so, I rose. He held on to me, and I to him.” Douglass’s grip was so firm that blood seeped around his fingers from Covey’s throat.

The two fought to exhaustion, to a standstill—after which, Douglass says, Covey never touched him again. “I was nothing before; I was a man now,” Douglass said of the fight. “His travail under Covey’s yoke became Douglass’s crucifixion and resurrection,” Yale professor David Blight wrote in his seminal biography of Douglass.

It was a story Douglass honed and refined in his three autobiographies. He retold it thousands of times in speeches around the country and abroad. In the world of literature and history, that fight and Douglass’s year of agony on the Covey property are abundantly noted.

The mud is thick on my boots when I get back in the car. I have to wait for three trucks to pass before I can turn onto the highway and head home.

America is in yet another pronounced brawl over who we are, which is inevitably a fight over our history and what to remember of it, and how. The Lincoln statue in Washington’s Lincoln Park is intrinsically part of that feud. Last year, amid the national convulsions over racial justice, authorities erected a high fence around the bronze Abe Lincoln and the kneeling freed slave to keep protestors from tearing them down, as happened with many other statues.

In the many times I have walked by that statue over more than 20 years, dog on a leash or kids in tow, I had always recoiled from its condescension. Whatever agency or free will the Black man had, it was all bestowed upon him by Lincoln, the Great Emancipator. In Boston, a replica of the same statue was quietly spirited away late last year. The inscription on that statue put all the light on Lincoln: “A race set free / and the country at peace / Lincoln / rests from his labors.”

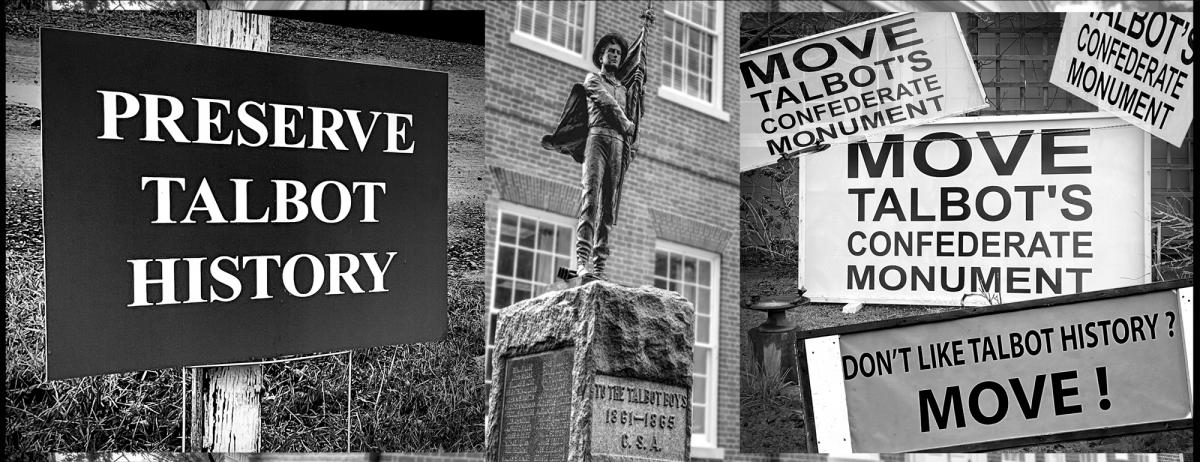

Here in Talbot County, where the muddy field sits along the Bay and where Douglass spent nearly half of his first 18 years, residents are caught in a similar fight over the large Confederate monument that stands in front of the courthouse in Easton, the county seat.

The “Talbot Boys” statue honors the county’s fathers and sons who fought for the Confederacy, though Maryland was unaligned in that war—the only such statue on public land in the entire state. Detractors want it moved somewhere else, out of sight, away from the main square, and have stuck signs in their yards that read: “Move Talbot’s Confederate Monument.” Supporters who insist it stay have planted signs in their yards that read: “Preserve Talbot History.”

The signs sprout thick along the roadways–Move versus Preserve—even as so many other aspects of the area’s history, where vital things happened, go unnoted or are replanted every year in soybean or corn.

What Douglass described as a mile’s walk from the roadway to the water is now less than half that. Storms have eaten away at enormous swaths of the shoreline, including the land where the Covey farmhouse once stood, though I so wanted the house in those woods to be his house, the walls tottering over, a pile of bricks in front, that the thought made me shiver when standing within those ruins.

Douglass litters his memoirs with physical detail. The gate to the Covey farm was made of “two huge posts, eighteen inches in diameter, rough-hewed and square.” The house was “wood colored.” Covey whipped him one winter’s day with thick shoots cut from “a large, black gum tree” on the edge of the woods. Several days before the big fight, on a sweltering afternoon in August, Douglass collapsed in exhaustion “under the side of a post-and-rail fence.”

You would search in vain today, as I have, for any remnant of the gate post, gum tree or post-and-rail fence. They have been taken by the seasons, the sea or the plow. The only constant is the soil.

Some fingerprints from the past remain. In Douglass’s day there was a Methodist meeting place where the New John’s United Methodist Church and its parking lot stand now across from the Covey farm. Douglass described attending one of the huge tent revivals there before his year with Covey and how he saw his owner, Thomas Auld, find religion. “I heard him groan, and saw a stray tear halting on his cheek,” Douglass wrote later, disgusted by the hypocrisy of the pious slave holder.

Maps going back nearly two centuries show a church where the current one stands. In the 1880s the dwindling band of White congregants gave it to the area’s Black citizens. A quarter mile away, Pot Pie Road still cuts to the left through the tiny town of Wittman, heading to where Douglass had once sought refuge on “PotPie Neck” during his brief escape from the Covey farm.

I begin to ask around, hoping to see what the people there might remember as a matter of lore in the absence of all markers or reminders. I make calls, knock on doors. I repeatedly call the field’s owner and leave messages, but get no reply. The owner of an adjoining property, who knew faintly of the Douglass story, recommends I talk to the man who farms the property now for its current owner. I find the farmer in his barn a quarter of a mile away, his breath steaming as he fills and weighs burlap bags with that fall’s corn kernels.

He shakes his head when asked about Douglass and Covey. “I’ve never heard of an Edward Covey, but I know a lot of other Coveys around here,” he says. He is talkative, helpful, friendly. “People know that farm as the Morris farm,” he says. “Pretty sure that’s the Morris house that is falling down in the woods.”

I duck into the Wittman Post Office, less than a mile down the road, where the postmaster is stuffing letters into various slots behind the counter. She grew up a few miles from the Covey farm and has lived along the road that passes it her entire life. “Nope,” she says, when asked if people ever mention Douglass’s time in the area. ‘I knew he was in St. Michaels, but not out here,” she says.

A furniture maker whose shop is within sight of the field is sitting behind a desk in his unlit showroom when I knock at the door. He speaks fluently of Talbot County’s history, and the struggle over the Talbot Boys monument. He knows a lot about Douglass and his time at the huge Wye River plantation across the Miles River, but not that Douglass had ever spent time right there, across the road. He is astonished when I tell him the story of the fight in the Covey field.

I find an old parishioner from the Methodist church across from the Covey field, an 84-year-old Black man. He is pottering in his yard a few miles toward St. Michaels when I pull into the drive. He has lived his entire life along that road, but he, too, shakes his head when asked about the field and Douglass’s time nearby. “Never heard a word of that,” he says, amazed. “I guess the people who knew about that sort of thing died a long time ago.”

As I keep asking around, I begin to stumble on history buffs who have dug through the writings, the maps, the old land deeds, are well steeped on the details of Douglass’s year there. All are seized by the potency of the place and the desire—some might call it an obsession—to pinpoint what happened where on a landscape that is perpetually changing. They guide me to locals of both races who have heard the stories since childhood and have different ideas of exactly where Covey’s house might have been. Some share the desire to erect a humble marker to note Douglass’s resistance there.

In the ebb and flow of memory and forgetting, the forces of remembering are fighting back.

Monuments attempt to embody an abstraction in granite, marble or bronze. A war, a battlefield, a person of note. Here strands the Great Emancipator. Or here astride his horse sits the doomed valiant hero of the Lost Cause.

Fields and woods do the opposite. They represent the absence, the natural forgetting in most cases, of an actual embodiment. Humans made of flesh and blood, anger and love and righteousness, did something noteworthy here, although the woods and the rains have since absorbed and washed it away.

We should tip our national memory away from statues and monuments and towards the remembrance of place. To preserve the memory, however painful, of what happened where. The human thread now woven through the land skews heavily in one direction, toward the valiant, the triumphant, and the victor. Or, in the eyes of the South, toward the martyred Confederate.

Road signs riddle the Mid-Atlantic attesting to where Washington slept, or dined with Lafayette; where Stonewall Jackson was shot and where he died; where Robert E. Lee entered the Shenandoah Valley or recrossed the Potomac. We are told of moments meant to affirm our national pride or stir the soul. Outside of St. Michaels, an old road marker tells of a skirmish in the woods there against the British in 1813, but no sign notes that Douglass was caught nearby, plotting to escape, and then marched down that same road in manacles to Easton.

Sign on Route 33 near Broad Creek, across from where Frederick Douglass was apprehended for plotting to escape in 1835

The events that give pause, that grate against our national self-image, go little noted along the roadways. Here 14 Indians were slaughtered…From this tree five men were lynched…From this port men and women were sold…In this field Frederick Douglass beat his white enslaver and emerged a man.

Forty-two years after he left the Covey farm, Douglass rose to give an extraordinary speech before an audience that jammed the whole of Lincoln Park. It was April 14, 1876, the eleventh anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination. The event was the dedication of that famous Lincoln statue near my house a mile from the Capitol. Gathered to honor the moment, and to hear Douglass, were President Ulysses S. Grant and his cabinet, the Supreme Court and many members of Congress.

Freed former slaves had raised the money for a statue to honor Lincoln for freeing them. The sculptor aimed to capture the moment that Lincoln’s proclamation had figuratively broken the shackles that bound the man kneeling at his feet.

In his speech, Douglass lavishes praise on Lincoln for many actions he took, but he is audaciously blunt in reminding the audience of Lincoln’s deepest predilections.

Lincoln “was preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men,” Douglass said. “He was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights of humanity in the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country.”

Three days later, Douglass wrote to a local newspaper about his discomfort over the Emancipation Monument. He wanted to see another statue set beside the Lincoln statue, to give it proper balance, he wrote. “The negro here, though rising, is still on his knees and nude. What I want to see before I die is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man.”

In writing that line he had summoned the image of that August morning four decades earlier, when he rose from the ground to fight back against Covey.

Were Lincoln Park there to honor not just the dead president but also the land itself, one might learn that during the Civil War, a vast tent hospital had once covered that ground. Walt Whitman had roamed tent to tent, writing letters for dying soldiers, helping as he could. The first soldier ever buried at Arlington Cemetery— Pvt. William Henry Christman, aged 20, of Pocono Lake, PA. –died on that site. His boots, belt and trousers were sent home to his family, at their request.

Debate over the Lincoln statue continues to boil, as it does around the Talbot Boys monument in Easton. There, too, the hidden layers of history run deep. Prominently listed among the officers on the latter monument is one Edward Napoleon Covey Jr., the eldest son of the slave breaker. The younger Covey was an infant when Douglass arrived at his father’s house at the start of that fateful year.

Sideview with The Talbot Boys in the foreground, Douglass in the background, and the flags at half-staff.

Fifty feet to the right of that monument stands a much newer statue of Douglass, erected 11 years ago after years of struggle, his arm raised in mid-oration. For now, anyway, Douglass shares the main square in the county of his birth with a monument honoring the eldest son of the man who beat him.

In his barn down the road from old Covey field, the farmer tells me he always plants corn in the field one year and soybeans the next, the better to balance the soil and not wear it out. Last year the field was all corn. This year, he says, he will plant soybeans again.

Neil King Jr. served for 20 years as The Wall Street Journal’s chief diplomatic correspondent, senior politics writer, and global economics editor. He works now as a writer and editor and divides his time between Washington DC and Claiborne, MD.

Jeff McGuiness was the senior partner of a public policy law firm based in Washington, DC, and founder of HR Policy Association. A fine arts major in college who served as a photographer in the Air Force during the Vietnam War Era, he has picked up where he left off 50 years ago with Bay Photographic Works. He lives in St. Michaels, MD.

[…] that in mind, I want to draw special attention to today’s Saturday feature, entitled “Statues and Fields” by Neil King, Jr. After a distinguished tenure as the Wall Street Journal’s foreign […]