The fevers of my youth have quieted, some. For one thing, I can think about falling in love more dispassionately. I’ve been thinking about it, recently.

These thoughts weren’t inspired by concerns for my aging libido. I was moved by an account I read written by the celebrated Cistercian monk, Thomas Merton. Merton describes an incident that occurred while he was walking along a city street in Kentucky. It was a transformational moment for him, an epiphany. He writes:

“In Louisville at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all these people and that they were mine and I theirs . . . and if only everybody could realize this –– but it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun. Then it was as if I suddenly saw the secret beauty of their hearts, the person that each one is in God’s eyes; if they only could see themselves as they really are, if only we could see each other that way all the time.”

His excitement about the moment was infectious, like a man in love might write or speak of his beloved but with this caveat: the experience had none of the possessiveness usually associated with such passions. The love was wholly generous.

Love songs play exhaustively on the radio night and day. Their lyrics describe the longing the experience evokes, the desire and the ecstasy, even the pain felt from the loss of a love. Many pop songs describe the beauty and the endearing attributes of the beloved. It is strange to me that we should understand so little of what can impact us so much.

Falling in love is as universal as the common cold and like the common cold, no one knows just how long it may last.

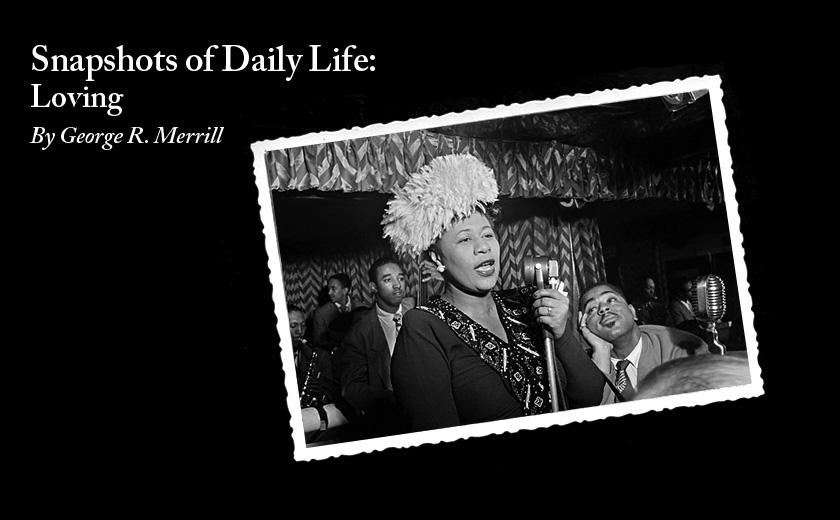

Ella Fitzgerald didn’t care about any of love’s secondary effects, like possessiveness or jealousy, or even duration but urged us all to just ‘fall in love.’ She was remarkably inclusive, encouraging just about every creature imaginable to fall in love. Years ago, she famously sang the pop song, “Let’s Fall in Love.” The song invites everyone ––the birds and the bees, of course–– but also kangaroos, chimps, jellyfish, clams, eels and goldfish to mention but a few. She concluded her invitation by singing, “Let’s do it, let’s fall in love”

What’s remarkable about falling in love is the way someone who might seem ordinary to you and me, becomes, in the eyes of a lover, incredibly beautiful. Freud had a jaundiced view of falling in love and commented on its most transforming characteristic, i.e., how lovers impute to their beloved, attributes that they don’t necessarily possess, or no one else can see. He called this a lover’s proclivity to “overestimate the love object” or as this thought is commonly expressed: “Whatever does she see in him?”

In grade school, I fell in love with Delores. She attended our church. I saw her as the personification of beauty and grace. In hindsight, I’d have to say she was quite unremarkable, even frumpy, and I would say further she probably looked a little like cartoon depictions of Little Orphan Annie. However, this is not what I saw. Her person released some kind of mystical agent within me, that, at a certain moment, awakened a latent capacity; an ability to experience the essential beauty of others who, at least by conventional standards, wouldn’t be reckoned beautiful at all.

I wonder now if, in those times when I fell in love, I was given a fleeting glimpse of how God sees me. What God sees as so sublime and good in us, we’re still too blind –– nor sufficiently evolved–– to see it in each other or in ourselves. For us, love occurs in transitory forms, like falling in love. We become then like God who, as the lover does, sees in the beloved what is invisible to anyone else. Seeing others, seeing ourselves, and seeing the world as God does is a stunning revelation for anyone.

Our human capacities –– such as they have so far evolved –– are still becoming; they’re slowly growing, expanding. To fully embrace the love we have latent in our own hearts, much less to experience it in others, I suspect would short out our psychic wiring. In our evolution, and I believe in our destiny, we will get there. How long, how long, though? Sometimes the waiting seems interminable.

Consumerist cultures like the one we live in, are filled with illusions: they promote glamorous people, shiny objects and expensive toys that urge us to desire and covet them so that we can have what glamorous people have. And like the toys children receive on Christmas, once acquired, by New Year’s Day are forgotten.

Falling in love’s shelf life varies. In all cases it serves a wider purpose in our destiny than just propagation and adventure. Birth control has changed how we think and feel about human sexuality and the nature of the bonding it can facilitate. Experience, though, teaches us that love points beyond propagation to a vision even greater, to something magnificent, and while our hearts long for this magnificence we can’t quite get it. One man likened embracing love to discovering fire. Paleontologist and Jesuit priest, Teilhard de Chardin wrote this about love’s ultimate destiny:

“Someday, after mastering the winds, the waves, the tides and gravity, we shall harness for God the energies of love, and then, for a second time in the history of the world, man will have discovered fire.”

Let’s do it.

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.