Recently, a northwest wind combined with a tidal low, emptied water from our cove. Herons and gulls lit on the mudflat to feed. They lingered there while the water was out. As the water rose, the birds retreated. They’ll return when the flats are exposed.

We, too, are always searching. It’s a sign of life.

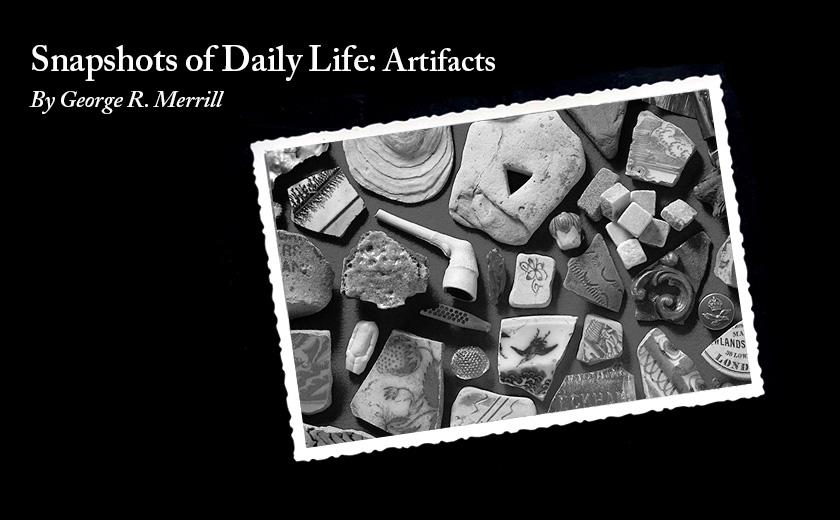

The Thames River snakes through London, England. Tides range anywhere from fifteen to twenty feet. Low tide exposes the riverbanks. There, mudlarks (people, not birds) scour and dig along its banks, ‘forebanks,’ in search of artifacts of London’s past dating from pre-Roman times. Mudlark and writer Lara Maiklem, seeks to nourish her spirit by feeding her imagination. She writes of mudlarking in her book, Mudlark: In Search of London’s Past Along the River Thames. “Mudlarking is a quest in two parts,” she says; “the hunt for the object and the journey to identify what it is and learn more about it.” Her imagination is fed by the ways that her fragmentary discoveries might open windows into the lives and habits of those who once lived in London. Her story is haunting. She caught my imagination in two ways: in describing her own imagination and the way she satisfied its hungers. Imagination is the locus of the spirit. It has appetites as the body does. We recognize its hungers when we feel curiosity. When curiosity is laced with wonder, we know our spirits are ravenous.

Her portrait of her school days was similar to my own. She, too, was a dreamer. She lived a kind of alternative world in her classrooms. She writes, “… my school reports… they were in all honesty, dreadful… one overriding theme throughout: my ability to dream my way through class… inclined to be rather dreamy… must be willing to concentrate fully… would benefit with more interaction in class… does not seem to realize that she must concentrate at all times.” Hers was my story, too.

Her teachers were gentle. Mine played hardball. In an irritated tone, my mother would hear how “George is always daydreaming in class… never pays attention… will not apply himself… he doesn’t stay on task… I don’t know where his mind goes.”

As Maiklem described her own school days, I felt my past legitimized by this kindred soul. She also enthralled me with her descriptions of mudlarking, the curiosity driving her messy and tedious tasks of eking out clay pipes, glass, pottery shards, Roman coins, and pins from the mud. She was really after the story they might tell.

Maiklem is a self-confessed dreamer. Dreamers romanticize. I would offer that certain romanticizing is more than just wrapping a gauzy film around the stern realities of life. It’s more a hunger to understand, while living in the now, how it was for those living in the then. Like compassion, romanticism is a way of knowing, attended by a feeling of belonging to the lives of others and participating in their reality. Romantics and mystics try unraveling stray threads by which the entire human family is knit together. Maiklem describes her search as “grounding.”

When I was young, my father and I would search for Indian arrowheads. He had a large collection. Some seemed new, others battered with time. He said they belonged to the Lenni Lenape tribe who lived in the Mid-Atlantic, roamed the coast and hunted here on the hill where we stood. What were they liking? Did they see the same landscape I did, I wondered? How marvelous it was to stand where they once stood, at a time long before I was.

My kin rarely talked about family history. I regret that. I’ve had so many questions. I knew only that my mother’s family were in the marine trades around New York Harbor and the Hudson River from at least a turn of the 19th century, and that my paternal grandfather was an “oyster dealer.” As I’ve aged, my imagination has hungered to know more. I began my own mudlarking. I didn’t scour the shores of the island on which I grew up. Instead, I perused the contents of an old file box dated ‘1946.’

The box contained only a few artifacts of my family history. The contents were a hodgepodge of legal documents, cards, correspondences, a few yellowed photographs, birth, death, and marriage certificates. Like Maiklem’s findings along the Thames, I Identified some objects, but not their story. I found a yellowed photograph of a Victorian sitting room. It felt strangely familiar. Why was it saved at all? Was there a story for me? Would the corridors of my memory reveal anything?

The room was small, cluttered with bric-a-brac and there were pictures on every surface. Tapestries hung on two walls; doilies were placed on chair backs, and a table stood in the middle of the room. A tablecloth covered the table, and sitting on the floor at each end of the table were cuspidors. All I recognized for certain was the chair –– a platform rocking chair, the Morris Chair that I had in my room as a boy.

Tiny fragments of life experiences, like the ancient shards Maiklem unearthed from the Thames, endure over time in the corridors of memory. The photograph revealed a room, but not one I recognized. Time had altered its looks, but the fundamentals remained intact. Would my imagination reveal the whole from the part? Eventually it did. I felt a thrill of discovery.

The photograph was the sitting room of my grandparents’ old Victorian house along the Kill Van Kull. I’d been in that room with my relatives for some fifteen years on Thanksgiving Days during my youth. Then, in the late forties and fifties, all the Victoriana, appearing in the photograph cluttering the room, had since gone. Like all ancient artifacts, time altered it.

I thought I saw the presence of what was absent in the photograph, the presence of my father. I remember him there in that room for the last Thanksgiving of his life. He died two days later.

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.