By the time young Richard Diebenkorn attained stature as an Abstract Expressionist, he was itching to move on—again—to explore new horizons with his painter’s toolbox. “You see, I was trying to demonstrate something to myself,’ he said in an interview for John Gruen’s 1955 book, “The Artist Observed.” “Namely, that I wouldn’t get stuck in any dumb rut.”

While he never totally abandoned his abstract inclinations—producing art as he felt it rather than as seen—Diebenkorn eluded ruts for the rest of his long, prolific career.

“Richard Diebenkorn: Beginnings, 1942-1955,” a traveling exhibition receiving its only East Coast exposure at Easton’s Academy of Art Museum through July 10, presents 100 paintings and drawings—many never shown before—that reveal the artist’s evolution from student to 33-year-old master of a modern American art form.

Because the show reflects Diebenkorn’s progression from classroom assignments—depicting the folds and shadows of a draped length of patterned fabric—to ever-searching expressions of mind’s-eye creativity—it’s best to view it chronologically. Start at the gallery to your left as you enter the museum and proceed clockwise from the introductory panel outlining Diebenkorn’s formative years, beginning with his 1922 birth in Portland, Ore., and San Francisco childhood. First, you’ll see his student assignment. (It deserves an A.) Other early works from his Stanford University days, before his other calling—World War II active duty—include representational watercolors of residential rooftops and fine-line ink drawings of fellow marines while stationed at Quantico, Va. (Art supplies weren’t allowed.)

His early Berkeley period preceding officer’s training (he flunked) exposed him to faculty disciples of Hans Hoffmann, although one instructor favored Cezanne. Both influences are evident in Diebenkorn’s untitled geometric watercolor-and-graphite pieces and the mortal combat in “Duel at Dawn.” The artist/marine renders loosely recognizable architecture in and around San Diego’s Camp Pendleton, where he was based before his dreaded mission to parachute behind enemy lines in Japan. But the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced Japan’s 1945 surrender. Diebenkorn’s team never deployed.

Married during the war, he and his wife Phyllis were parents of an infant daughter as Diebenkorn resumed art studies at the California School of Fine Arts, where the faculty included Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still. Diebenkorn’s abstracts began to reflect a more defined approach epitomized in three untitled paintings displayed as a triptych—two with geometric shapes on a flat plane and another of irregular shapes in a perspective alignment. His 1947 “Untitled (Magician’s Table)” is a deft nod to Surrealism while you might glimpse De Kooning with a darker palette in an untitled gouache from Diebenkorn’s 1948 solo exhibition at San Francisco’s California Palace of the Legion of Honor.

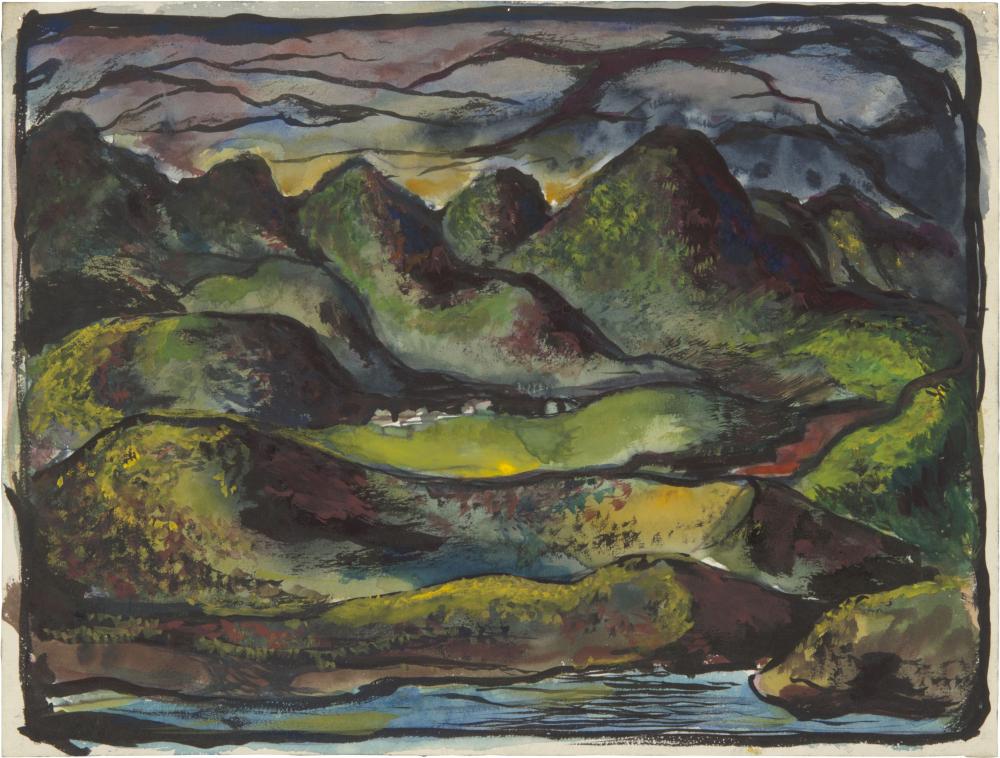

Abstracts with a sense of place, on larger canvases that Diebenkorn could by then afford, dominate the gallery across the lobby: structured but still nonobjective landscapes on beach (Sausalito period) and desert (Albuquerque) from the early ‘50s. His Urbana period at the University of Illinois was inspired by a major Matisse exhibition, leading to abstracts that playfully hint at identifiable figures. You might spot an owl (unintentional?) among these 1952-53 watercolors.

In a small gallery down the hall, there’s no mistaking the objects in Diebenkorn’s first mature figurative painting, “Untitled (Horse and Rider)” from 1954.

Where his “Beginnings” eventually led—spanning a lifetime up to 1993—are seen in catalogs beneath a huge black-and-white photo of Diebenkorn, the marine. The 1997-98 Whitney exhibition volume includes images from his “Ocean Park” series featured in the 1978 Venice Biennale—sea and sky, maybe both, as viewed from a window. As usual, Diebenkorn keeps you guessing and engaged, avoiding ruts and realism for a half-century.

A display upstairs features works by a few Diebenkorn contemporaries, drawn from the Academy of Art’s collection, among them Baltimore’s Amalie Rothschild (“Reclining Figure” drawing, 1955) and two Thomas Hart Benton lithographs (“Morning Train” and “Night Firing,” 1943).

“Richard Diebenkorn: Beginnings, 1942-1955”

Daily through July 10, Academy of Art Museum, 106 South St., Easton

Lecture: “My Father, Richard Diebenkorn,” by Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant, 11 a.m. June 1

academyartmuseum.org, 410-822-2787

Steve Parks is a retired journalist, arts critic and editor now living in Easton.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.