George (Bud) Ivey is the President and Senior Remediation Specialist at Ivey International Inc., the patent holder of Ivey-sol, which is a product slated to be used in a Maryland Department of the Environment-approved pilot-scale application at the Chester River Health premises to clean up a heating oil spill.

Dave Wheelan, Executive Editor at the Chestertown Spy, reached out to Bud over the phone recently to discuss Ivey-sol. Excerpts from the interview follow. The topics of conversation include: concern about the safety of the Ivey-sol product; some background about Bud and how he got involved in environmental remediation work; how frequently Ivey-sol is used where water supply contamination is an issue; the worst-case scenario for Chestertown whether Ivey-sol is used or not; and how Bud and Ivey International got involved in the Chester River Hospital oil spill case in the first place.

Dave: There’s some anxiety in Chestertown not only about the oil spill itself, but about the introduction of Ivey-sol, which some see as a novel approach to dealing with the spill. I wanted to have this conversation to give you a chance to talk about your background and how you came to develop the Ivey-sol technology.

Bud: My background is primarily as an organic chemist. I spent a lot of time in the lab synthesizing compounds in pursuit of a Masters degree, but I am a people person and did not want to spend too much time in a lab. I found myself spending a lot of time thinking about how to explain what I was developing to people, to translate the science. I also studied geological engineering. I have been interested in environmental problems from a young age. I was exposed through the media to the environmental movement during my youth, as well as through outdoor activities and participation in Boy Scouts. I earned a degree in project management and got involved in the environmental management industry. When I finished my studies I went to work for an environmental consulting firm and in 1993, I went off on my own and started a company. I started doing collaborative work with Universities right from the beginning to connect research and development with practical applications in the field because I saw the need was there. Some of these efforts eventually led to patents for parts and processes for Ivey-sol.

Dave: How does Ivey-sol work? And how often has this been used in situations where the water supply is a factor?

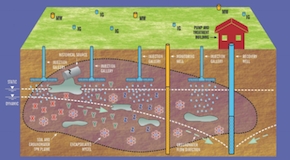

Bud: Oil of course is not very soluble, so it mostly floats on water. But it is soluble enough that we would not want to drink water contaminated by oil and other petroleum products, because even though the solubility is poor, our tolerance to exposure is relatively low from a toxicity perspective. The oil tends to sorb to the soil – it tends to stick. I realized from some work I had done in the mid-80s with transfer molecules that you can actually grab something from the oil phase and bring it to the water phase and from the water phrase to the oil phase. I realized I could make chemicals more miscible. I was interested in how to desorb contaminants chemically, physically and biologically, so that’s what I worked on and developed.

In terms of our experience with situations in which the water supply is a factor, I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that 80% of the sites in which our technology has been used was either cleaning up contaminated ground water, or we were not too far from a place where we could impact a water source. There is heavy reliance on ground water for drinking water in the United States – I think I’ve read that 50% of our drinking water supply in this country is from ground water – so it’s nearly impossible to avoid being involved in such situations.

When I look at California, most of the applications we did there were near active water supplies and production wells. So, the process we went through was very challenging, very detailed, public consultation, the whole nine yards. I’m happy to tell you the Los Angeles Water Board, which is a very strict regulator – we were the first and only approved surfactant they ever approved for an In situ application.

Dave: There is concern about what’s in Ivey-sol since it’s patented and the products are not readily disclosed. What is your response to that?

Bud: I think that’s a really good question – an important issue. I see myself as a stakeholder in my own community – I’m a stakeholder in general and I care that Ivey-sol is safe. So, I had the foresight to use compounds that could be ingested, to use a somewhat general term, to produce compounds that are environmentally friendly. I suppose I was green before I even knew what green meant. You can ingest these chemicals, they are being used in medicines now, they are really biodegradable – not partially, but fully biodegradable.

Also, we have EPA approved methods for analyzing our products. So if a client is applying our product and wants to see if it’s removed, you can measure it. If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it. You can take a water sample and analyze whether the product is still there. And we can demonstrate that we can manage our chemical in a responsible way.

Dave: What is the worst case scenario Chestertown could face if it went with an option like this – if it decides to use Ivey-sol.

Bud: Any contamination in the soil and ground water near a water supply presents a risk regardless of extent of contamination. The previous work to control and contain the site in Chestertown has been effective, or we believe it is – I haven’t heard of any claims otherwise. But a problem remains. I think leaving contamination there in Chestertown presents a continued risk to the aquifer. Continuing pump and treatment is good, but not enough. We will be applying Ivey-sol in a way which looks very similar to other site applications, so we’re following a proven model, nothing we haven’t done anywhere else.

We’re going to inject Ivey-sol where it will make contact with some residual contamination, desorb it, and remove it, all from the same well. We’ll do baseline sampling before anything is done and through that process we’ll take some time-based samples so we can measure the effect, which is nice site-specific feedback. The site has lots of wells, there’s lots of history, there’s good understanding of the ability to contain ground water on the site. So, this is easier to understand than a spill that just happened.

Also, we’re going in first with a pilot-scale application, working on a very small area, to show people that it works. I’ll be following this and I’ll use data to make sure we only inject enough so the process works and we do the job properly. The process will naturally evolve in a way that is responsible and measured in combination with the regulators, who will have eyes over our shoulders and make sure the way Ivey-sol is being applied is responsible.

I think we can get the last bit of residual contamination out so the real or perceived risk to the local aquifer is minimized – you always want to approach zero.

Dave: How did this all come about in the first place? I’m under the impression it was a bit serendipitous?

I was on a project not too far from Chestertown and I stayed in a Bed & Breakfast there. I was down at the waterfront having a bite to eat and the hockey finals were on. I asked the couple beside me if they knew what the score was and we started chatting. The gentleman was a doctor at the hospital and mentioned the situation at the hospital after I mentioned what I did for a living. This was around 2010.

The doctor introduced me to Scott Burleson and I chatted with him about this and he took me on a tour of the site. I met the local consultant. I put the idea of Ivey-sol out there and they had not heard of it before. We stayed in touch and in the Spring of 2013 and he told me they had gone through the closure process. But there was some rebound contamination and they asked if I could get involved here. I told them this was the sort of situation I deal with all of time and that led us to where we are today.

Kevin Shertz says

Editor,

All well and good, but let’s not lose sight of the big picture: we, as a community, need more information from the company and the Hospital as to what’s being planned. We, and are water supply, are being treated as guinea pigs. We are not being provided with adequate information. Bob Sipes’ feelings on this matter should be more than an ample example of this. If Bob is concerned, I’m definitely concerned.

My concerns of this situation are both as a land owner in the Town but also as a businessman… The Chester River Brewing Company will be tapped into the municipal water supply of Chestertown. Bad water = no beer. No business. Zilch. Nada. Of course, at that point, the business will be the least of my worries, as I’ll be struggling alongside every other landholder to liquidate themselves of their land holdings on a community with a tainted water supply.

I have no doubt that Bud Ivey is a thoroughly decent person and genuinely interested in the health, safety and welfare of our Town’s water supply. But science doesn’t give a pair of dingo’s kidneys about intentions… it deals in facts. We’re guinea pigs here in Chestertown. And neither the Hospital or the company itself have provided us with the information we need to make a factual conclusion about the outcome of what’s being planned.

I can’t emphasize this enough. If our water supply becomes tainted, we’re all screwed. Majorly screwed. All so the Hospital can save itself $50k a year operating a series of pumps for the oil spill that they caused.

MB Troup says

Editor,

I would be interested in some clarification on the question which mentions that the product is patented, thus the solution cannot be disclosed. My understanding is that patent protection is exactly the reason why Mr Ivey COULD disclose the specifics. Of course, I am guilty of being a fan of the show “Shark Tank.” Maybe that isn’t the best source for my information.

Bob Sipes says

Editor,

Mr Ivey has been asked repeatedly to provide complete case studies of any sites where this product has been used within 1500 ft of a water treatment plant that uses the same aquifer for drinking water. To date it HAS NOT been provided AT ALL. It is not enough that he says it, we need the records, to include extensive site testing before during and after the applications.

This project has an extensive history, over 20 years worth of recovery well operation that has kept the water supply safe. And keeping this water supply safe needs to be the primary goal and focus of every person and entity involved.

Kevin Shertz says

Editor,

Until I hear from Bob Sipes saying the words, “I am satisfied with the remediation plan,” I’m going to be against what they’re trying to do. Thank you Bob for your work and experience.

Keith Thompson says

Editor,

I do admit that I find a certain irony in that the MDE apparently trusts that Ivey-Sol is not going to risk the town water supply and approved the hospital’s use of it because, after all, it’s not the state’s drinking water supply that is at risk. I also admit that I find a certain irony in that many area residents, politicians, environmental organizations, etc. have been awfully comfortable in seeking environmental solutions out of Annapolis or Washington, DC (TMDLs, Plan Maryland, etc.) until they encounter a problem is in their own backyard. This is a Chestertown issue and kudos to the town government for standing their ground, but this isn’t unlike the county standing their ground with their involvement in the Clean Chesapeake Coalition over concerns about the Conowingo Dam.