The president’s budget, released in early March, called for the creation of a national fund to finance repair of the nation’s crumbling roads, bridges and other infrastructure — an idea also proposed by a freshman Maryland congressman.

Rep. John Delaney, D-Potomac, wants to fund infrastructure repair by bringing home billions of dollars in foreign earnings from U.S.-based corporations. The congressman said he has been long concerned about decaying infrastructure.

Delaney’s Partnership to Build America Act would create a new way to pay for these repairs. Corporations would provide the money by buying bonds in The American Infrastructure Fund.

In exchange, they would be allowed to bring back money locked up overseas without paying the full 35 percent corporate tax rate.

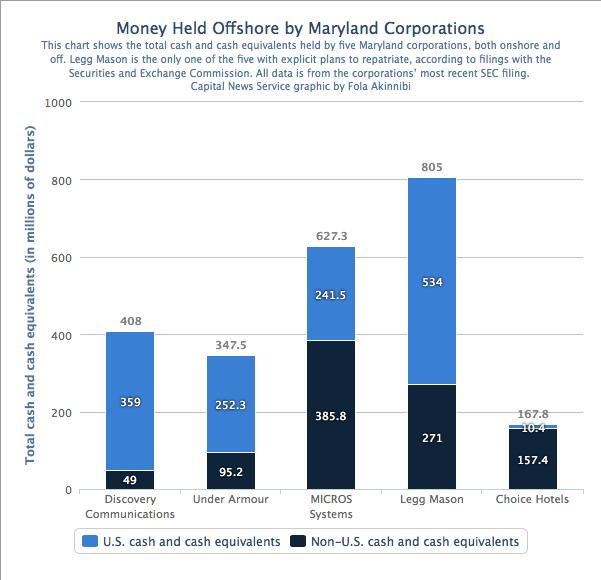

Delaney’s bill could come as a relief to corporations with large foreign operations that have deferred paying U.S. corporate taxes on their overseas earnings indefinitely. For example, 10 Maryland-based multinational corporations, including Columbia-based MICROS Systems Inc. and Baltimore-based Under Armour Inc., are holding a combined $3.5 billion overseas, according to filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

While it would mean a major tax savings, none of the 10 publicly held Maryland companies contacted would comment on the proposed legislation.

While it would mean a major tax savings, none of the 10 publicly held Maryland companies contacted would comment on the proposed legislation.

One expert said there’s little incentive to bring the funds back with so much business opportunity overseas. Instead, it makes sense for U.S. companies to let the overseas funds stay put and postpone a U.S. tax bill.

“It’s better to defer,” said Michael Faulkender, a finance professor at the University of Maryland’s Smith School of Business.

Further, the Delaney proposal is out of sync with many plans to overhaul the U.S. tax code, he said. “Every proposal on the table is for the corporate tax rate to go down, not up.”

Rich Badmington, W.R. Grace & Co.’s vice president of global communications, said most of the Columbia chemical company’s revenue comes from international operations. The company plans to continue investing in those operations.

“We are able to do that without bringing cash back to the U.S. because we are continuing to invest,” Badmington said. “(Research and development) is a function that requires continuing investment and we have quite a lot of that outside the U.S.”

President Barack Obama’s latest budget plan called for the creation of a government-owned entity to finance infrastructure projects. Delaney said the president’s support for something similar to his bill was “great,” and said it shows how much momentum the bill has.

“We’re very optimistic about it, we have strong bipartisan support,” Delaney said.

The bill has 57 co-sponsors in the House and 12 in the Senate, including Sens. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and Michael Bennet, D-Colo., head of the Senate Finance Committee’s Taxation and IRS Oversight subcommittee. Hearings have not been scheduled for the bill.

Under the tax code, corporations can avoid paying taxes on foreign earnings as long as the money is being permanently reinvested overseas. When the corporations decide to bring these funds back home, a process called “repatriation,” the money then is subject to U.S. taxes.

Originally, the tax exemption was meant to help U.S. corporations compete overseas, said Mitchell Kane, a tax professor at New York University’s School of Law. Companies claimed paying taxes in two countries would put them at a disadvantage and the government responded with the exemption, he said.

The plan was to have the companies pay foreign taxes, which in many cases are lower than the U.S. tax rate, and then pay U.S. taxes when the money was repatriated. After this process, the company would receive a credit for any foreign taxes paid, Kane said.

Allowing such an exemption has created an incentive for companies to keep their money overseas and defer the U.S. corporate tax, said Jane Gravelle, an economist with the Congressional Research Service. But parking money offshore isn’t a long-term solution for companies, she added.

“They may think they can hold their breath forever and borrow money,” Gravelle said. “How long are they going to be able to do that? Shareholders eventually want dividends.”

This exemption could result in $265.7 billion in lost revenue for the federal government through 2017, according to a 2013 report by Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation.

For now, however, companies aren’t likely to repatriate without a major tax discount.

W.R. Grace has more than $1.1 billion held overseas and would have to pay $149.7 million in taxes if it was repatriated, according to SEC filings. That money will remain overseas, except in instances where repatriation would result in minimal or no U.S. taxes, the company said in its most recent SEC filing.

MICROS Systems, a Maryland-based computer hardware and software producer, has about 61 percent of its cash and cash equivalents, $385.8 million, held internationally with no plans to repatriate, according to the company’s most recent filings with the SEC.

Maryland-based apparel company Under Armour has $95.2 million, or 27 percent, of its cash and cash equivalents held overseas with no plans to bring it back.

Spokespersons from MICROS and Under Armour could not be reached for comment.

Other companies have begun to repatriate their foreign funds, which Kane said could help cover corporate expenses. McCormick & Company, a spice, herbs and flavoring manufacturer, repatriated $70 million in 2012, according to the company’s most recent SEC filings. Even still, most of the company’s cash is held in foreign subsidiaries, the filings said.

A spokesperson for McCormick and Co. could not be reached for comment.

Some of the largest U.S. corporations make about half of their money internationally, Delaney said. The bill is just a way to get some of it back.

“It creates a way for some of that money to come back, which is good for our economy,” Delaney said. “And it creates this large-scale infrastructure fund, which is good for our country.”

Instead of government funding, the American Infrastructure Fund would raise cash through a $50 billion bond offering. Companies would buy the bonds at a 1 percent fixed interest rate and a 50-year term, in exchange for a chance to repatriate a certain portion of overseas earnings tax-free for every dollar spent on bonds.

A bond to repatriation ratio would be determined by an auction and could result in companies paying an effective 12 percent tax rate, Delaney said. Money raised in the bond sale could then be leveraged and loaned to state and local governments for projects.

The auction process will benefit both the infrastructure fund and the corporations, which will be able to find a price that is right for them, Delaney said.

“We’ve talked to them and they’re very supportive of it,” he said.

The American Business Conference, Associated Equipment Distributors and Terex Corporation are among those supporting the bill.

Tech giants and pharmaceutical corporations have lobbied for a repatriation holiday since the 2004 American Jobs Creation Act allowed them to repatriate at a discounted rate. Because of the intellectually-based capital that these companies thrive on, it is sometimes easier for them to keep assets overseas.

For example, Apple has $124.4 billion held overseas, according to the company’s most recent SEC filing.

The 2004 bill reduced repatriation taxes to 5.25 percent if corporations promised to invest the money at home. The one-year holiday is widely regarded as a failure because it spurred an increase in repatriation, but not an increase in jobs or investments, according to a report by the Congressional Research Service.

“The argument was that it would be a stimulus” to the U.S. economy, Gravelle said. “Most people who studied this found out it was being used to repurchase shares.”

Share repurchases are a common way to boost stock prices.

Corporations used the money to pay stockholders dividends and pay off debts, which doesn’t make for a good stimulus, she continued. Instead, the holiday created a “moral hazard” and companies have parked money overseas, waiting for the next holiday, Gravelle said.

Delaney’s bill has short-term benefits but doesn’t address the larger problems with the tax code, Faulkender said. Corporations will want to move more and more operations overseas if they can find discounts on U.S. taxes, he added.

“If you signal that firms are going to realize a lower tax rate, even after repatriation, on their foreign operations than on their domestic operations, you’re going to incentivize even more offshoring,” he said.

“I don’t think that’s good for the U.S. economy.”

By Fola Akinnibi

Capital News Service

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.