Two recent art projects developed by Washington College’s Environmental and Public Art Studio have initiated a unique bridge between the College and the Chestertown community.

During the Fall semester, Professors Alex and Kelly Castro led their students to the college-owned property around historic Stepne Manor (across from Wilmer Park) to experience creating “environmental art”. A natural palette of “found” materials, from soil and field grass to fallen branches and leaves, were used to construct emblematic designs honoring the transience of nature and its cycles of growth and decay.

This winter, students were challenged with an even more daunting artistic task—their mission was to interpret the sensitive and complex subject of race relations and inequality evident throughout Chestertown’s history, and to express their ideas as a public art construction.

The project description presented to the students read, “Chestertown’s relationship to race has been a complicated one and continues to be to this day. It will be the artist’s concern to create a work that not only speaks to the subject, but also conveys the subject to a broad audience.”

“Ted Maris-Wolf, Deputy Director of the C.V. Starr Center, was an integral part of this project. He gave us a needed ‘sense of place’, not only geographically but within a historical context,” says Kelly Castro.

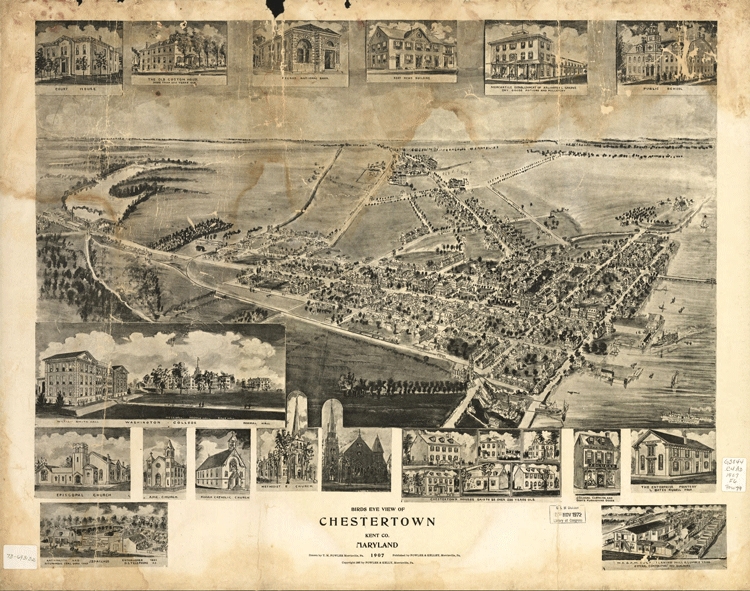

Maris-Wolf configured a strategic walking path through Chestertown using a 1907 map and, with long-time resident Armond Fletcher, guided the students from the waterfront to the College while pointing out the invisible history of the community.

The map was included in a packet of historical material given to each student: records of slave sales, reward offers for runaway slaves, a sales notice for “Negroes for Sale” from an 1828 issue of the Chestertown Telegraph, an 1892 Chestertown Transcript account of a notorious lynching, interior photographs of the old Chestertown jail, a collage of famous African American musicians who played at the Uptown Club, and even a 1766 letter from George Washington to Josiah Thompson asking Thompson to sell his ‘troublesome’ slave, Tom, while in the West Indies and to be compensated (after commission) with molasses, rum limes, tamarinds sweetmeats and the rest in more Spirits.

“A tour through Chestertown is about discovering how African American spaces get rearranged and public memory gets erased in the way that others don’t. It becomes a long tradition of erasure,” Maris-Wolf says.

One of the more profound moments occurred when students learned that the cemetery sites for the African American Janes Church near Wilmer Park were relocated to Quaker Neck in the 1920s due to property development.

1907 Map of Chestertown used for Professor Ted Maris-Wolf’s walking lecture about the town’s often hidden history.

Jessica Brennan, ’14 conceptualized a living monument of flowers to commemorate this displacement, writing that “I was shocked by how recently it was considered acceptable to displace an African-American cemetery in the name of development” and hopes that if her project were to be used as a memorial residents would be interested in maintaining it.

“One of the cool things to realize about this project is that many of these students are not art majors. They are coming at this project without any predisposed ideas of what art should be about. They’re just using their instincts and imagination,” Castro says.

Camille Maisons, WC ’14 concept of a historical tour with seven letter guide markers spelling “RESPECT” placed throughout the town.

And they tackled the project from many different directions, from windpower generators and a town tour linked together by sequential letters on buildings eventually spelling the word “RESPECT”, to draping the steeples of Janes United Methodist and First United Methodist churches with colorful banners to symbolize peace and harmony.

Kylie Nottingham, ’14 was moved by the G.A.R. Charles Sumner Post building on Queen St. and proposes a black granite memorial stone with the 400 GAR members’ names etched in contrasting white, large enough to invite rubbings.

Thomas Urban, ’16 devised an intricate set of windmills, gears and pulleys to represent one area where the color lines were blurred: as dockworkers. His vision would be to create this mechanism in Wilmer Park overlooking the river and boatyard.

Each of the twelve students arrived at a unique vision of how best to symbolize Chestertown’s often hidden and sparsely recorded history. Hopefully one of the project proposals, or one like it, will spur the actual construction of a public art installment to encourage us to unveil the past and to honor the present with an open dialogue about inequality, and thus the quality of all our lives.

“There’s been a lot of interest in this walk from outside the College and we are planning another walk that will be open to the community,” Castro says.

The projects are now on display through June at the Historical Society of Kent County, Bordley building, 301 High St. 410-778-3499, Hours are Friday and Saturday from 11am to 3pm until further notice.

Front photo is of Camille Maison, WC ’14, working on her environmental art project last Fall at Stepne Manor.

Hope Clark says

Editor,

Fabulous!

Marge Fallaw says

Editor,

From above:

“Kylie Nottingham, ’14 was moved by the G.A.R. Charles Sumner Post building on Queen St. and proposes a black granite memorial stone with the 400 GAR members’ names etched in contrasting white, large enough to invite rubbings.”

Membership in the Sumner Post never came even close to 400 members. Annual veteran membership during the post’s heyday probably never exceeded 30, as Prof. Barbara Gannon (now of the U. of Central Florida) hypothesized from her research at the Library of Congress for her dissertation (and later book) on African Americans in the Grand Army of the Republic. (There was also a women’s auxiliary of the post, the Women’s Relief Corps.)

Perhaps the student confused GAR membership with local African American participation in the Civil War, which is commemorated by the black-granite obelisk erected in Memorial Park at High and Cross streets downtown in 1999. When that monument project began in late 1996 and early 1997, the intention was to list on the monument the names of all African American servicemen with a Kent County connection. At first, that seemed feasible (financially and logistically), given that in a local publication about Kent County in the Civil War only about 120 Kent African American participants had been identified. However, after I began my own research (mainly at at the Md. State Archives), it soon became clear that a much greater number could be documented. When I finally stopped systematic work on my database (after deciding not to spend days going through records in Pennsylvania, where numerous Kent men enlisted), it included information on at least 430 black soldiers and sailors (an imprecise and incomplete number, partly because of possible duplicates and aliases and garbled/illegible/imprecise names). We (the monument committee) concluded it was safe to say on the inscription that more than 400 served. (The program for the April 1997 site-dedication day did list the c. 430 in the database at that time.) Regrettably, the inscription subcommittee chose to categorize them all as having been in the USCT (United States Colored Troops) of the U.S. Army whereas, in fact, a significant percentage served in the still-unsegregated U.S. Navy, not the Army.

Marge Fallaw

James Dissette says

Thank you for this. We’re always looking for accurate information about our local history. This certainly went by me unchecked and is a perfect example of how all of us must participate in this dialogue.