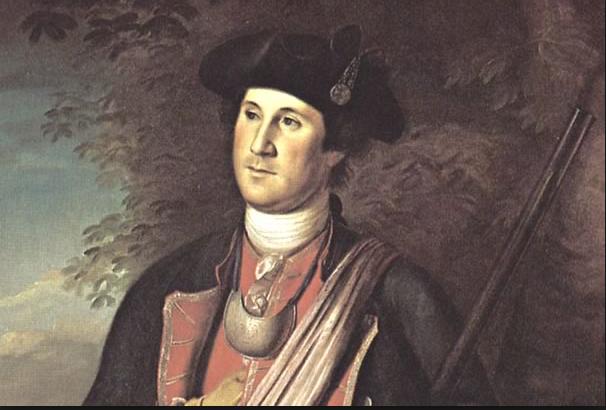

Surrender, humiliation, and poor management are not what comes to mind at this time of year when we salute the memory of George Washington. We honor instead the Father of his Country, the leader of the Continental Army, the modern Cincinnatus who surrendered his sword and general’s commission at Annapolis after independence, and the first President of the United States, elected unanimously.

But the young Washington, often overlooked, made many missteps and bad calls, as at Fort Necessity in 1754, where poor planning and misjudgment resulted in appalling casualties, humiliating defeat by the French, and the seizure and publication of his personal diary. Indeed, the inexperienced commander could be impetuous, highly emotional, and even reckless at times.

How did that young man with ambitious dreams become one of our country’s greatest political and military leaders, the gold standard by which we judge our leaders today? What can we learn from Washington’s unlikely and awe-inspiring ascent from military failure to statesman and founding icon?

To help us answer these questions, Washington College, which General Washington and his officers helped create in 1782 as the new nation’s first college, asked five eminent historians to discuss Washington’s virtues and explain what made him a giant among his contemporaries, the greatest leader of his day, respected and admired around the world.

What emerged is a complex portrait of leadership, revealing some of the many elements that formed Washington’s character and his deliberate effort to be a new type of leader for a newly democratic society. He displayed an amalgam of virtues, some rooted in his eighteenth-century society and others that are timeless.

“Physical courage under fire,” writes Stephen Brumwell, author of George Washington: Gentleman Warrior, was central to the honor code of Washington’s day. Yet even by that standard Washington was exemplary. He did not just lead his men into battle, his calming presence rallied his men to victory in the battle of Princeton in January 1777 and at Monmouth the following year. His suffering with his troops during the winter of hardship at Valley Forge is famous; less well known is that he never took leave during the entire war.

Whether in battle or in office, Washington had a highly developed sense of honor and what constituted honorable behavior. According to Professor Richard Beeman, Washington was “motivated in his public life by civic virtue. . . . His ability to subordinate his personal interests to the public good in all public behavior and demeanor served as examples for others to follow.” For example, Washington refused to accept any pay for his service as either commander-in-chief during the Revolutionary War or later as president, despite the financial hardship this caused him. Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Gordon S. Wood insists, “Above all, he was wary of being perceived as having a private interest or stake in something. . . . He had a strong moral sense of how he should behave.”

Washington also learned from his mistakes and surrounded himself with talent. Author Richard Brookhiser reminds us that Washington “drew upon others who were in some sense smarter than he was, but he himself knew what to do and where he wanted to go.” It took remarkable self-confidence to hire Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay as his first cabinet officers. They were men of “true ability, all much smarter than he was,” says best-selling historian Joseph Ellis. A lesser man would have feared being overshadowed or diminished by these ambitious rivals. Not Washington, who wrote that “much abler heads than my own” were needed to achieve the larger mission of uniting the still fractious states and forging one country from many contentious individuals.

Washington prepared himself intensively for leadership by emulating successful people he encountered and by following a volume of 110 Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour, which he meticulously copied as a kind of how-to manual for self-made success. Maintaining a fastidious appearance, refraining from public displays of emotion, and generally keeping quiet in good company, he became the George Washington we recognize today, the iconic man Brookhiser dubs our “founding CEO.”

What leadership lessons can Washington teach us? How do ideas of leadership today compare with those of the self-educated and self-made Washington?

We spoke to three more experts about those questions. The leadership characteristics most needed today, according to Paul Volcker, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, are “a steadiness in purpose, personal courage, and unstinting allegiance to the common good—the public interest.” Rebecca Rimel, president and chief executive of the Pew Charitable Trusts, agrees that “leadership is not about self, but about stewardship: the care and cultivation of resources not your own.” However, she cautions that leadership is more challenging today than before because of the “rapid pace of change. Effective leaders must be able to embrace uncertainty, and be both flexible and comfortable with the challenges and opportunities that come with it.” Dr. Ralph Snyderman, chancellor emeritus at Duke University, says that “heroic leadership is harder today,” because one answers to more stakeholders than before and must demonstrate greater transparency and accountability and less deference to specialized expertise.

All these people believe that leadership can be learned but society needs to do a better job of providing more opportunities for young people and role models for them to emulate. And they believe that effective leadership must be guided by a strong moral compass and unshakeable ethics. Washington certainly would have agreed.

On this President’s Day, we would do well to honor not only George Washington’s singular accomplishments but the emerging leader who grew into the Father of his Country, who developed discipline, cultivated courage, and learned from his early experiences. The leadership lessons of the young George Washington are more than relevant today. They speak directly to a new generation of young people who aspire to lead our communities and our country.

This article is by Mitchell B. Reiss, the 27th president of Washington College, in Chestertown, Maryland.

Reprinted from the Forbes Leadership Forum from February 12.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.