On Thanksgiving Day in 1963, six days after the Kennedy assassination in Dallas, I watched the 27 second Zapruder film in its unexpurgated entirety, projected onto the wall of a living room of a friend’s house in Washington, DC.

The following day, Life Magazine would present to the world a cluster of black and white images lifted from the 8mm color film taken by Abraham Zapruder in Dealey Plaza that fateful Friday in November. In a way, those are the images we all recall most easily. Somehow, black and white stripped the images down to the core tragedy of the event.

Fifty years later, Jedediah Wheeler, a friend and classmate from those days, tells me that we had watched the film together in a house where only two years earlier the young President had held his Inauguration dinner. He’d been celebrating his narrow election over Nixon in the same living room I witnessed a recording of his death.

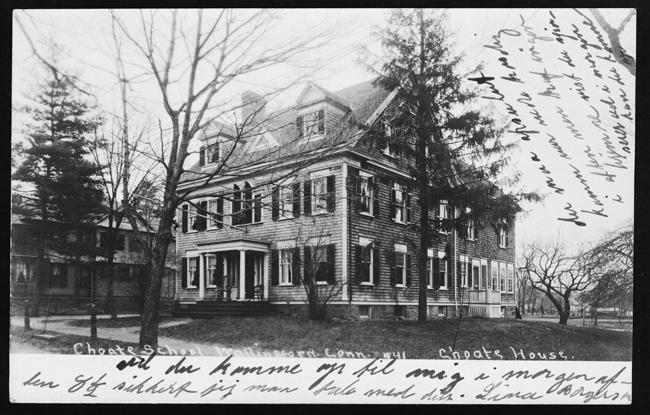

Five days earlier, in Wallingford, Connecticut, my roommate and I were being interviewed by a local ABC News affiliate rushing to put together a collage of JFK memories and background stories. At the time, we were living in John Kennedy’s old room at The Choate School.

Six months earlier I was failing French at a boys’ school in Dallas, Texas, and begging the gods to swing in on their savior wires, gather me up and deliver me from cowboys speaking in tongues. Armadillos and blood red rain from panhandle dust did not encourage any affection for the area. It was not a good time in my life.

The arc from French class in Dallas to watching the Zapruder film in Washington DC, delineates a surreal trajectory of experience in my life, so much so that I actually began to doubt its reality or at least wonder if I had embellished or diminished it so much that my current memory might be misshapen, a mere hint of its original minting. Memory is a little like a perpetually rewoven coat—the one you might be wearing today might have little resemblance to the one you bought. It spurred some research and reconnections.

“Well, all we seem to have left from the demolition of Choate House is a chair. I think there was a door at one time, but no telling where that is,” says Choate Archivist, Judy Donald. “But we do have some footage of your November 1963 interview. I remember seeing it. You were a bit flummoxed, a deer in the headlights.”

That was a nice way of saying that I appeared to be having a meltdown on television news.

…

Wallingford, Connecticut on the Quinnipiac River was a far cry from the bleak cityscape of 1960s Dallas, Texas. I arrived there in July, 1963 for a “make it or break it” summer school session—my grades in Texas, except English, were lower than basement dirt and except for Ian Fleming and learning how to throw a hard breaking curve ball, school was a reoccurring rendezvous with boredom, dreary uniforms, Latin choir and long bus rides. And bus rides led back to home. And home was one long dirge of disappointment braided with alcoholic violence, unidentifiable emotions and dark, unexpected actions.

In other words, I was highly motivated to succeed in summer school and it became easier when I discovered that my French instructor could actually speak English, although I failed to learn why I needed to learn La Marseillaise. Maybe it was my last name.

Choate House, The Choate School, Wallingford, Ct. Kennedy’s room was to the right of front door, first floor. The dorm has since been demolished. This image is of a postcard.

At summer’s end, with passing grades, I was enrolled at The Choate School and assigned to a first-floor room in Choate House, probably one of the original buildings on campus and not destined for many more years of use. It had an ancient mustiness to it, trembling radiators, strange faux-Victorian lacy curtains and dank common room furniture from the 1940s. It was not quaint and I sensed winter was not going to be a cheer-fest. The eight or so rooms had metal bunk beds, two desks, two chairs. The rest was left up to our imaginations or parents who wanted to ease our Spartan pain. Embarrassing to admit, I asked the kindly dorm-master if I could have a nicer room on the third floor. He declined. His antidote for my disappointment was revealing that “President John Kennedy was in that room. Maybe some of it will rub off on you.” It did.

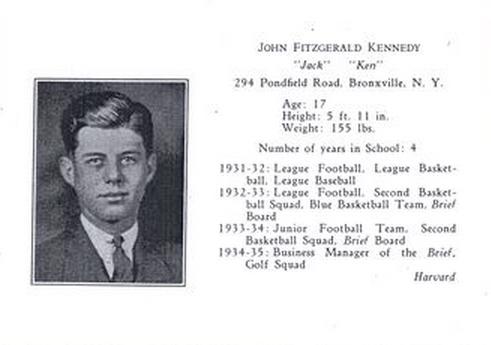

Kennedy anecdotes are part of the warp and weave of Choate history. We knew about his penchant for practical jokes and we also knew that his behavior got him into serious hot water. Even a school with blue-ribbon creds rooted deep in the soil of what is often considered WASPish excess and elitism, did not take lightly his serial pranksterism. After Kennedy and his cohorts blew up a toilet with a cherry bomb, George St. John, one of the iconic New England prep school headmasters, had had enough of the boy’s behavior and called for an emergency chapel meeting to declare an end to “mucking” about from these unruly boys. It is said that St. John, towering in the pulpit above the student body, held up piece of the destroyed toilet and shook it in JFK’s direction. Kennedy, undeterred, dubbed his group of friends “the Muckers Club” and continued to flout the rules with pranks until their dismissal from school and eventual reinstatement after a visit by Joseph Kennedy with a promise to the headmaster that “Jack” would behave.

John Kennedy’s Senior photo in the 1935 Choate yearbook.

I was recently told that Joe Kennedy might have made a gift of a needed movie projector to the school at that time. Perhaps it was to thank the headmaster for his patience, a patience that seems in retrospect worthwhile as the young Kennedy shifted gears more toward academics, or at least farther away from practical jokes. The headmaster would note later that he had become fond of the boy’s wit and spirit and conveyed to his son and successive headmaster, Seymour St. John, how much he’d respected how the young Kennedy had succeeded.

…

Late November in Connecticut is a perpetual dusk of erratic weather—black ice, brittle leaves fluttering over dead winter lawns, and a wind that devours wool and spits it out as wet snow. On Saturday, November 23rd, life itself was funereal. President Kennedy had been killed in Dallas. Except for a few boys wandering from the Winter Exercise building, students were in their dorm master’s living rooms watching the nonstop flood of news pouring in from Dallas and Washington news bureaus.

We were all processing the assassination. There was a weird, unspeakable dread that crept into us like the November cold, slid into us like an icy serpent to coil around our hopes and expectations. Everything was altered. The world of adults, the parents we innately trusted as children to keep life magically in order, took on a new dimension of vulnerability. It was if we suddenly awoke to a different movie of the world. Little did we realize what awaited us in the next seven years.

My dorm, Choate House, sat on a shallow valley’s shoulder, as did most of the central campus of larger dorms, library and dining hall. It was uphill from where I was walking that day and I remember the wind was blinding. As I crested the hill and lifted my head for a moment to get my bearings I was startled to see a truck with a media logo parked in front of our dorm. I quickened my pace, passed the truck, followed cables from the truck up through the front door and into the room I shared with a kid named Ned Palmer. Ned was sitting on the lower bunk bed under arc lights. A huge camera was perched on top of a tripod. Our room was flooded with blinding white light. It was easy to see that this was not going to be good. I looked at Ned. Ned looked at me.

“It’s the room,” he mouthed, giving me a heads-up.

My stomach dropped three floors. Of course, the Kennedy room. News team, News. Me in the news. Heart racing. No breathing. Panic started to creep in as I was ushered in to sit next to my roommate. White light, people in profile, voices instructing us to look toward our left, then to our right. In one second I’d lost contact with the English language and any semblance of projecting a confident expression. I was a mind-blown mess falling into a pit of adolescent awkwardness with nothing to grab.

“So I see you boys have been reading Kennedy’s “Profiles in Courage,” the reporter announced as he pulled it from our bookshelf. I looked at Ned. Got nothing but deer eyes in the headlights. I had nothing. I’d never seen the book before. Did the reporter plant it? Someone had to say something. Suddenly it was no longer Eastern Standard Time. It was Universal Time, and each second thumped like heartbeat.

“Um, we are thinking about reading that for extra credit, “ I blurted, or something similar. Right after I join the circus, find a plastic surgeon and change my name, I thought. We were devastated. We are 15, we don’t know anything, go away, we wanted to scream.

Mercifully, by the time the piece came out it had been heavily edited. Most of the babbling had been cut. While my roommate seemed to retain a kind of stoic acceptance of the interview, even then I was aware that I appeared as if I were sitting in the front row of Judgement Day and things were not looking up. How does one answer a question like—“So what does it feel like to be in President Kennedy’s old room?” I don’t remember what I answered but I’m sure it wasn’t what I was feeling. The room and the question made me profoundly sad. 28 years before that question was asked, John Kennedy might have been sitting in the same spot making plans for Thanksgiving. I didn’t know how to say it then. I’m not sure I know how to say it now.

•••

Jedediah “Jed” Wheeler and I became friends during the early months of our freshman year. I don’t remember the circumstances but would venture to say that we shared a streak of youthful sarcasm if not full-blown comic cynicism (without the scornful inference). We did not seem to gravitate toward the cliques that naturally self-construct within any group of people about to spend four years together in the sequestered social environment of boarding schools. Much has been written or suggested about the cruelty of cliques or the dissolution of the privileged. I didn’t see any of that. I saw kids whose family names were universally recognized along with kids like me from middle class family. We all struggled over our classes, played football and baseball, had meals and daily chapel together. Perhaps I am romanticizing, but I don’t remember hearing about one fight. We were far from the boys in Lord of the Flies.

As Thanksgiving approached, many of us with families too far away for short vacations looked forward to friends’ invitations. Jed invited me to Washington D.C to spend Thanksgiving with his mother, brother and two sisters. My outstanding memory of that place—aside from Jed’s elegant and gracious mother— was its majestically sweeping staircase. It was cinematic. It begged for Greta Garbo. The ceilings were cathedral, the rooms like caverns of sunlight.

The Wheeler home in Washington, DC as it appears today. The living room where the Zapruder film was shown appears at right.

Jed and I were playing a game of Stratego after Thanksgiving dinner. As we moved our spies and scouts about trying to avoid bombs and capture flags, a family friend arrived and asked, “do you boys want to see a film?”

Hank Suydam was a Washington bureau chief at Time-Life. I remember him as being galvanic and having one of those energy fields that parted clusters of people as he walked through crowds. Jed recalls him as a “swashbuckler” journalist. He’d covered the Freedom Riders, the Jimmy Hoffa jury tampering case, the Bay of Pigs invasion, and was instrumental in Time-Life’s acquiring the Zapruder film on November 23, the day after the assassination. Time-Life bought the original and one copy.

Hank Suydam was walking around with the Zapruder film in his coat pocket and we were about to see one of the most important documents in American history projected on the Wheeler’s living room wall.

And there we were, Thanksgiving Day, the 6 of us, Jed, Jed’s two sisters and a brother, his mother, Hank Suydam, and me, watching as the wall of their living room burst into a half minute of terror, blood spray and the heartbreaking frenzy of Jackie Kennedy’s panicked reach for help.

To say that 27 seconds is a sliver of time is not to understand how that tragedy magnified the moment into a full stop, and plucked it out of the river of fluid moments to suspend it like a dark amulet over the brocade of history.

It is possible we watched the original Zapruder film, but more likely we watched its copy. Nevertheless, what we witnessed that day was more than the world would see for quite a while and more than our hearts and minds would ever want to experience again. It did not seem as vague as subsequent media showings over the years. It was saturated with color and sharply defined.

Some curtain of naiveté about the world had been brutally ripped down to reveal a wider and more complex horizon of dark and dangerous possibilities.

To discover recently that the young President of the United States had celebrated his 1961 Inauguration in the same room added such a horrible counterpoint to that time 50 years ago that only now am I making room in my psyche to accept it.

Jed’s father had been a friend of JFK’s at Choate and his mother, Jane, had long been a staunch supporter of the Senator’s bid for the White House and had hosted many social events on his behalf at the Wheeler residence. To this day I cannot imagine her suffering as she watched that film on the wall of the room where he once celebrated the first day of his Presidency. In the same room, we witnessed his last.

As Jed wrote to me recently, “and then we went back to school.” I could hear his old voice saying that. By intonation, he’d gone to the meta-story. He was saying, “we went back to school to learn, but what we’d experienced that day in Washington was so profoundly sad, bizarre and powerful that it would flicker within us, just slightly out of focus like a handheld home movie, for the rest of our lives.

Portrait of John F. Kennedy by William F. Draper, commissioned by The Choate School. Although Kennedy could not attend the the presentation, he sent a recording to then headmaster Seymour St. John.

Listen to recording of JFK thanking Choate for the portrait

Jane Wheeler says

Editor,

To the author: Jim – I have to say I had forgotten that you were with us that day. While you were fourteen at the time, I was just eleven. Today as a parent of young boys, I would like to think I would hesitate to show them such a film – particularly within days of it happening. But Hank and Mother were caught up in the raw excitement around the existence of the Zapruder film, and I don’t think my Mother realized until it was too late how graphic it was, how much devastation it actually captured (and of course many of the images were hidden from the public for many years). It was a time and a happening that is difficult to convey, not only to ourselves but others. You did so beautifully with great care. Many thanks. – Jane

Stephan Sonn says

Editor,

Footnotes nicely put.

Jamie Kirkpatrick says

Editor,

I was a year ahead of Jim at Choate and remember that November day 50 years ago like it was yesterday. I was on my way to the laundry when I heard the news of the president’s assasination. I went straight to the chapel and sat there alone for a couple of hours trying to understand what was unfathomable. I’m still haunted by the memories of that day.